Using the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO) 1% and 2% individual taxpayer data for the period 2003-04 to 2018-19 income years, we reconfirm that, even before the covid-19 pandemic, the average salary and wages (hereafter ‘wages’) for males is higher than females and based on the current trends this will take approximately half a century to close.

Moreover, we find that the younger generation is struggling to see real growth in wages.

Mean wages are consistently higher for men compared to women

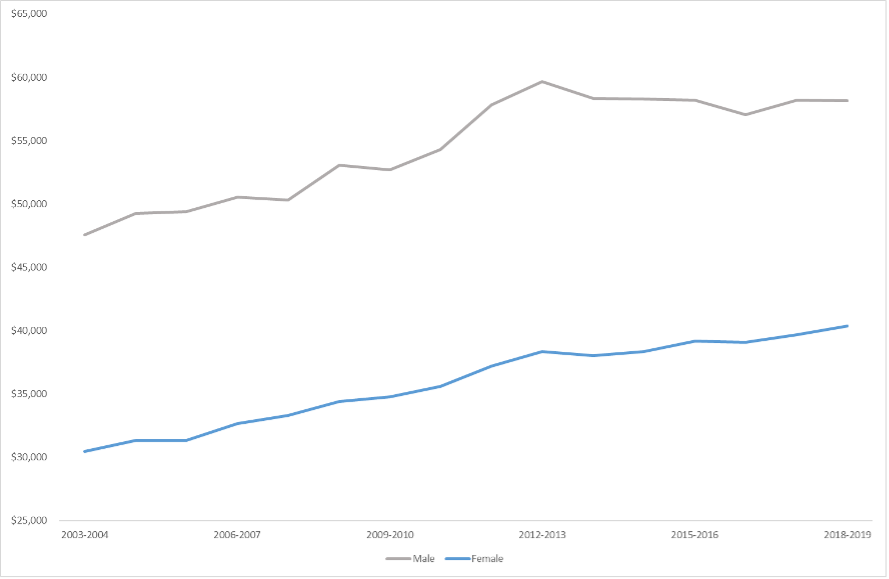

Wages represent the largest component of taxable income by a substantial margin. Over the sample period it represents approximately 80% of taxable income. Figure 1 presents the mean wages over time partitioned by gender.

Figure 1: Mean Wages by Gender for the period 2003-04 to 2018-19

Figures are indexed for inflation. Source: Australian Taxation Office

The first observation, aligning with Ross Garnaut’s view of Australia’s ‘dog days’, is that mean wages grew consistently for both men and women over the 2003-04 to 2012-13 period. Average male wages grew 25.4% over this period, whilst average female wages grew 25.9% (indexed). In the following six years however, average male wages went backwards by 2.5% whilst average female wages increased by only 5.3%.

The second finding is that men earn more than women. In 2018-19, the average wages for men were $58,134, compared to $40,387 for women.

This equates to average male wages being 43.9% higher than female wages.

Unlike the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s gender pay gap measure, which is based on equivalent full-time earners (and in 2018-19 was 20.8%), this data encompasses all taxpayers. Whilst the wage differential we find in the ATO data has reduced from 56.1% at the start of the sample period, based on the current trend, it will take another 54 years for male and female earners to become comparable if trends observed in the past will continue in the future.

It is important to note however that this data is pre-COVID.

The Grattan Institute highlight that prior to the pandemic, more women had been working than ever before, yet largely on a part-time basis:

The cost of childcare combined with additional taxation and loss of family benefits means that for many women there is little or no financial benefit from increasing their paid work beyond three days a week. – The Grattan Institute

A recent report by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency confirmed that the pandemic has had a larger impact on women.

Similarly, the Greens give particular attention to the contrasting position of women and young people over the pandemic:

Women and young people were already behind before the pandemic, but over the last 18 months, these trends accelerated. Women were more likely to lose their job, lose hours, do more unpaid work at home, and were less likely to get government support through JobKeeper… – Greens

Moreover, the Tax Institute note that the tax and transfer system design deters secondary income earners. Reflecting on the work by Miranda Stewart, these are more often female.

Results by age group

Since 2019, the Coalition’s tax cuts are described as delivering more than $31.6 billion in benefits to more than 11 million workers. However, the largest tax cuts are found to go to the highest income earners.

Whilst Australian taxpayers aged between 15 and 24 received $2.5 billion in tax cuts (on average, $2,430 per taxpayer), other age groups such as those aged between 25-34 and 35-44 have received higher tax cuts of $8.4 billion ($3,400 per taxpayer) and $7.5 billion ($3,410 per taxpayer), respectively.

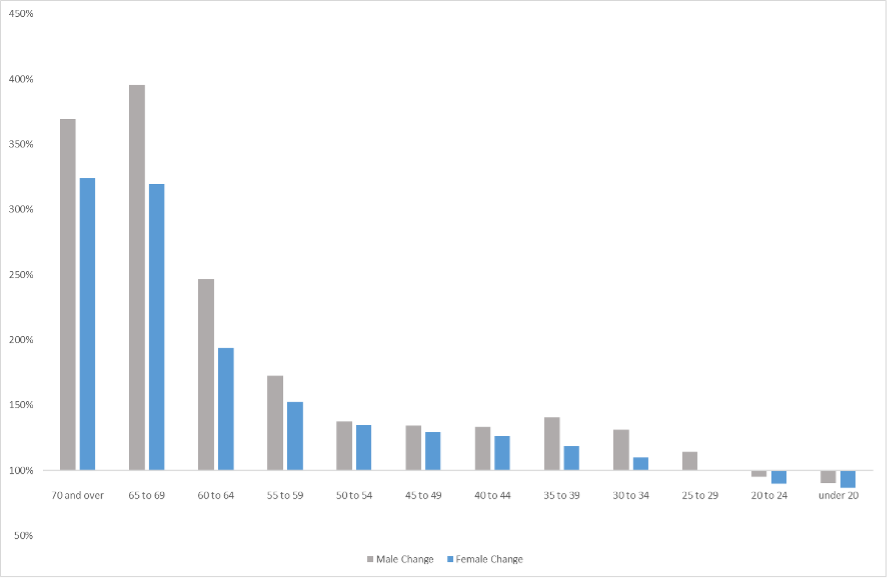

Using ATO data, we find that the indexed increase in mean wages over the 2002-03 to 2018-19 period was 22.2% for men and 32.5% for women.

Partitioning the data by gender and age (see Figure 2), we find there is no real increase in mean wages during the period for women under 29 years.

Moreover, both males and females appear to struggle under 25 years. The real mean wages for those cohorts have gone backwards since 2003-04.

Figure 2: Mean wage change for the period 2003-04 to 2018-19

Figures are indexed for inflation. Source: Australian Taxation Office

There is a real issue for youth with respect to wages.

Whilst salary levels have increased over this period, these increases have accrued to older cohorts.

Critically, for women, most age groups are worse off. Although we observe males experienced a jump in wages between 35-39, which is reversed between 40-54, before substantially growing thereafter.

This data, however, reflects a change based on age-groups – it is not reflective of particular cohorts moving through the system. So, the disadvantage we observe for Australia’s younger generation is not individual per se – rather young people more generally.

This disadvantage lasts longer for females.

It is important to note that whilst the increase in wages for those aged over 60 may appear substantial, the wage base for them is substantially lower.

Implication of skewed representation for tax reform

Men earning more than women is nothing new.

The advantage of men over women is traditionally the case in budget policy.

Women having a greater presence in the lowest income bracket and being underrepresented in the highest brackets leads to tax cuts favouring men.

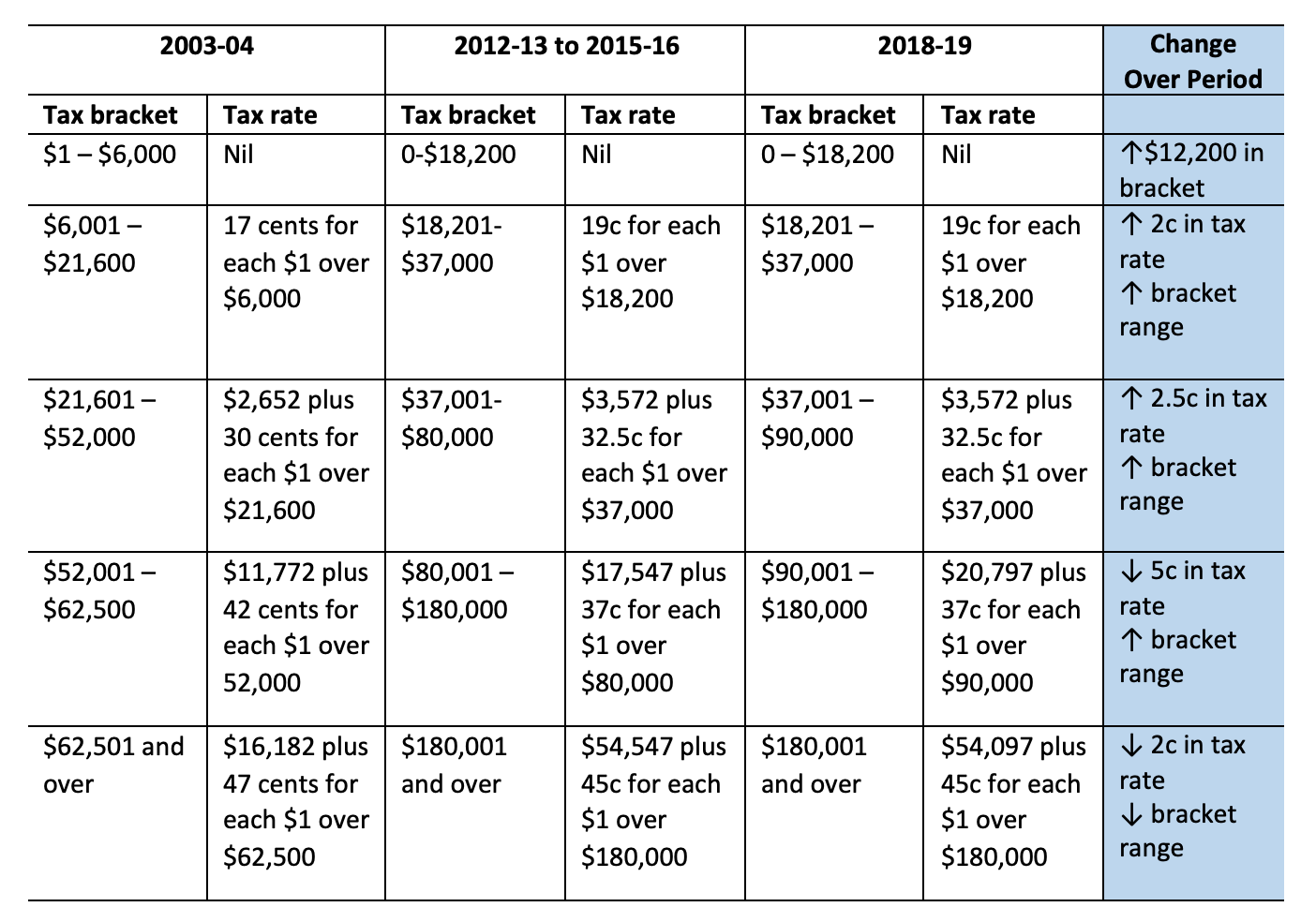

Table 1: Sample tax brackets for the period 2003 to 2019

Source: Australian Taxation Office

As reflected in Table 1, whilst the tax-free threshold has increased by $12,200, the progressiveness of tax rates flatten. This is further accentuated with subsequent stages of tax cuts.

Take for example, the Coalition’s three stages of tax reform announced in the 2018-19 Budget. This was initially slated to cost approximately $143.9 million in revenue forgone – split between $91.8 million applicable to males and $52.2 million to females.

Although the stages were subsequently sped up, concern was raised in respect to gender inequity:

The stage 3 tax cuts will go mainly to male, high income taxpayers. Half will go to the top 10%, 72 per cent going to the top 20 per cent while the bottom half get only five per cent and the bottom 20 per cent get nothing. Men will get twice as much of the tax cut as women. – Matt Grudnoff, The Australia Institute

A key component of the tax package benefiting those earning less than $126,000 is temporary, coming to an end in 2021-22: the low and middle-income tax offset (LMITO).

For high-income earners, stage 3 cuts are permanent.

We recognise, however, that earning a higher wage means that men pay more tax. Despite this, men have been found to receive a disproportionately large tax concession. According to the Australia Institute, whilst men pay 65% of the tax, they receive 70% of the tax concessions, compared with women who pay 35% and receive 30% in concessions.

Moreover, the Tax Institute highlight the impact of interactions within the family group leading to higher effective tax rates:

[O]nce the tax and transfer system interactions are accounted for, including higher childcare costs, higher income tax payable and loss of government benefits, the effective marginal tax rate of secondary earners becomes extremely high — in some cases, over double the top marginal personal income tax rate of 47% – The Tax Institute

This has similarly been examined by the Grattan Institute and Miranda Stewart, for example. The latter finds this effect deters women from working, particularly those with young children. These impacts have flow on effects, including inequality in superannuation.

Where to from here?

Our analysis reconfirms that the average wages for males is higher than females. Based on the current trends this will take approximately half a century to converge.

Importantly, this does not include the significant impacts of covid-19 on women’s participation in the workforce.

Moreover, the younger generation is struggling to see real growth in wages. Regardless of gender, younger Australians are going backwards. This trend may be expected to persist longer for females.

Other Budget Forum 2022 articles

Trusts and Tax Avoidance – Extension of Funding for ATO Taskforce, by Sonali Walpola.

Vehicle Taxing Dilemma Between Environment and Inequality, by Yogi Vidyattama, Robert Tanton and Hitomi Nakanishi.

Budget Reveals No Plan for Disaster Volunteering, by Jack McDermott.

A Fairer Tax and Welfare System for Australia, by Ben Phillips and Richard Webster.

Claiming Crypto Donations under Division 30, by Elizabeth Morton.

The Budget, Fiscal Policy and an Outbreak of Inflation, by Chris Murphy.

Natural Disasters and Government Policy Challenges, by John Freebairn.

Petrol Excise Cut in the Budget! What About the Transition to Zero-Emission Cars? by Diane Kraal.

For Social Infrastructure and Tax Reform, We Need a New Federal Fiscal Bargain, by Miranda Stewart.

A Free Lunch From Government Debt? It Certainly Looks That Way, by John Quiggin and Begoña Dominguez.

On the Limits of Fiscal Financing in Australia, by Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya.

Thanks for the response. I would note that women (and their husbands) who like children are likely to have more than a pigeon pair. If you have three children under 5, first, you probably want to do the childcare yourself and, second, it would be cheaper to get someone to help in your home with the kids. The childcare subsidy schemes deny couples this sort of choice. A neutral tax system would allow it as an option.

As for logic in the tax-transfer “system” (the word system does it too much credit), the tax system refuses to recognise income sharing with spouses, children or wider family whereas the welfare system wants to income test on such assumed income transfers!

But there is a political logic – maximising (a) tax revenue and (b) dependent voters living off the State.

Pingback: Budget Forum 2024: Stage Three Tax Cuts, Permanent or Temporary Relief to Address Cost-of-Living Pressures? - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog