This post was originally published as part of the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Policy Brief series. Read Part 1 here.

Improving the budget process

Overall, the Australian Survey results suggest that the Government does not reveal sufficient information to the public in some stages of the budget process, and that the process prevents the public from participating the budget process effectively and holding the Government accountable for the fiscal decisions it makes.

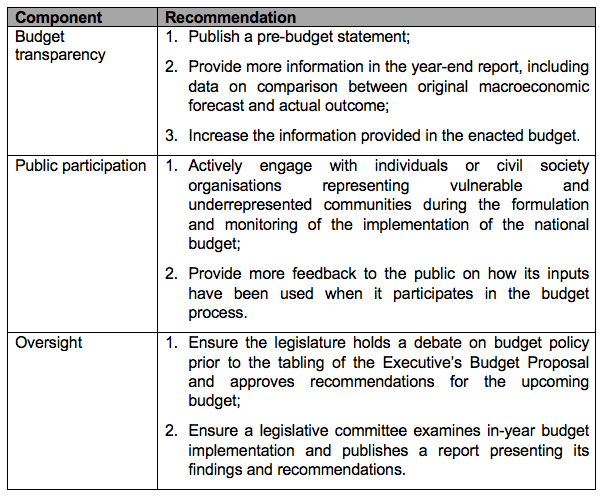

In the country summary report, the IBP has made some recommendations for Australia to enhance the budget system. Table 1 summarizes the recommendations.

Table 1: OBS 2017 recommendations for Australia

To have a budget system that is efficient, effective and accountable, it is important that each pillar of budget accountability — transparency, participation and oversight — fulfils the highest standard at each stage of the budget process. Any reforms must also recognise the challenges specific to the Australian budget system.

Do we have adequate pre-budget transparency and deliberation?

The Treasury invites pre-budget submissions and does some consultation with individuals, businesses and community groups in the budget process. However, there is no feedback to submissions. The Survey finds that there is a lack of pre-budget transparency in Australia because the Government does not release a pre-budget statement (thus a score of 0). There is also no adequate deliberation because the Government does not permit a parliamentary debate to scrutinise budget priorities.

Some might argue that pre-budget transparency in Australia is not as bad as the score indicates. For example, the Government provides information about its broad fiscal strategies before the release of the budget, either through policy speeches or press conferences by the Prime Minister and the Treasurer. Economic forecasts and anticipated revenue, expenditures, and debt for the coming fiscal year are also available in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) report.

However, it is increasingly expected that, for good governance reasons, governments should publish a systematic and comprehensive pre-budget statement. The two countries that pioneered budget transparency reforms around the same time as Australia in the 1990s, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, both produce such a statement. This can have positive effects on both public participation and institutional oversight in the budget process.

A pre-budget statement that provides all the relevant information enables the public to participate in the budget process in a more informed manner from the beginning. This is also in line with the latest Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency’s (GIFT) Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, among which the Timeliness principle recommends that governments should engage the public as early as possible when options for decision are still open. The pre-budget statement also allows parliaments to scrutinize their government’s broad fiscal strategies in a pre-budget debate, without this being lumped together with the discussion of detailed funding allocation in the budget approval stage.

Public participation needs to be more interactive and inclusive

In the Australian budget system, there are avenues for public participation through consultations held by the Government. However, these are still inadequate according to Survey requirements. The latest round of the Survey on participation utilizes the GIFT Principles. The GIFT Principles contain higher requirements for public engagement than previous standards. These higher standards partly explain Australia’s low score in public participation.

The GIFT Sustainability Principle calls for more regular and interactive engagement between the public and government officials. Consultations held by the Australian Government typically call for written submissions and there is little opportunity for further deliberation with the public. In Australia, the Citizens Budget only presents a summary of the executive’s budget proposal and there is no attempt to identify what information the public really wants.here is no requirement that the Government provides feedback on pre-budget submissions.

There should also be a systematic attempt by the Government to engage vulnerable and underrepresented communities in the budget process. Disadvantaged communities such as Indigenous Australians, recent migrants or rural and remote communities, may face more obstacles than others to participate in the process. The Survey finds no concrete and proactive steps by the Government to include disadvantaged communities in the budget process. One possibility is the use of citizen juries to engage citizens in policy formation and debate.

The global IBP report presents some innovative approaches by governments, that go beyond traditional consultations to engage the public and to ensure budget information is well understood by them. For example, civil society organisations are the mainstay of public participation in the Philippines’ budget process as more than 80 per cent of Filipinos are affiliated with them. These organisations are granted formal authority under the Budget Partnership Agreement initiatives to have access to spending information, participate in consultations and engage in oversight and evaluation of completed projects (see Box 5.3 in the report). This ensures consistent public participation throughout the whole budget process.

Meanwhile, public participation in Brazil is institutionalized as Public Policy Management Councils, which consist of elected officials, citizen representatives and experts. The councils have the authority to review municipal, state or federal ministry budgets and if the budget is not approved, the federal government can withhold financial transfers to the relevant agencies.

Plenty of financial information, lack of distributional information

While Australia was once at the forefront of promoting budget transparency, the enthusiasm seemed to fade after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. There is growing disillusionment among voters with the Government and democracy, in a time of difficult fiscal choices. Australia’s budget contains less information than in the past about distributional effects of budget policy on taxes and welfare, either by income or gender, which could help to inform the public debate about such choices. There are also questions about how reliable the budget estimates are, particularly the government revenues.

While Australia performs strongly in terms of the financial information provided in the Government’s budget proposal, the Survey confirms that distributional information is missing. The Australian budget does not present the impact of taxes or expenditures by income or by age to illustrate the financial impacts of policies on different groups. In the past, the Government provided “cameo” tables, which show the projected impact of policies in the real disposal incomes of different hypothetical families, but this practice ceased in the 2014-15 budget.

The United Kingdom has progressed further than Australia as it now regularly includes a supplementary document in its budget to illustrate the distributional impact of tax and welfare changes on households.

Australia also does not provide any analysis of the budget by gender. This is in contrast to the 1980s, when Australia was a pioneer in introducing gender budget analysis. The gap is now filled to some extent by civil society: the National Foundation for Australian Women has been producing reports that presents a “gender lens” on the budget since 2014-15. Recently, the Senate Economics Committee requested advice from the PBO on the gender impact of personal income tax cuts that had been proposed in the 2018-19 Budget.[1] This kind of information would be a valuable input into budget deliberations and policy development.

Limitations of the Survey

While the Open Budget Survey provides a detailed assessment of the budget system, it has its limitations. For example, the Survey assesses only the availability and comprehensiveness of budget information. It does not assess questions of accuracy and credibility. The IBP has identified this as an issue and is commencing a research project to identify problems in budget credibility across countries.[2]

In Australia, the reliability of revenue estimates, and thus the Government’s target of returning the Commonwealth budget to surplus, have become contentious in recent years. The Treasury has been criticised for using overly optimistic future economic growth scenarios and thus projecting an unrealistic fiscal balance target.

The Survey also focuses more on financial information and less on information about distributional and other aspects of the budget. On participation, the Survey assesses only the formal, direct participation opportunities in the budget process. It ignores other informal or indirect avenues, which may not be captured by the Survey, but also provide opportunities for the public to participate in the budget process.

For Australia, it is important to note that the score on participation or oversight does not recognise the role of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) established in 2012. The PBO makes an important contribution as an independent fiscal institution and Australia is one of the 18 countries in the Survey that has such an institution. The PBO’s functions include providing policy costings to all parliamentarians and conducting research and analysis of budget and fiscal policies. The PBO also carries out research into structural features of taxing and spending with long-run budget impacts. However, the PBO does not have a direct role in oversight of the budget or in engaging public participation. There may be scope to strengthen this role within the existing mandate of the PBO, or even to broaden that mandate.

The Parliamentary Budget Officer Jenny Wilkinson observed at the Australian launch of the Survey report that it is not unusual for a parliamentarian to propose a policy that one of their constituents has raised with them. So, political avenues and the PBO itself provide scope for public participation in the budget process.

The Survey considers only institutional oversight of the budget. What is not captured by the Survey is the non-governmental oversight provided by civil groups and the media. For example, as mentioned before, while a gender budget analysis is not provided by the government, reports have been published by activists and academics to provide a gender perspective of analysis to the budget. This analysis is after the budget, however, and does not directly contribute to formulation of budget policy.

Finally, the Survey concentrates on central or national governments; however, budgets are important at other levels of government in Australia and other countries. A country may perform very well at the central government level but budgeting at state and local levels may be opaque.

There are a range of other detailed issues for Australia’s budget that arguably are not identified by the Survey, including the relationship between the budget and future-oriented reports such as the Intergenerational Report; and consistency in measurement and reporting of revenues and expenditures from year to year. Some of these issues may be tracked over time, in future Australian Surveys.

The value of the Open Budget Survey

The budget is where the “rubber hits the road” for government policy. It is an important bridge between citizens and the state as governments decide how public resources are raised and spent. Empirical evidence suggests that greater budget transparency could improve fiscal decision-making and make corruption more difficult.[3] It should also make governments more accountable to citizens.[4]

The Open Budget Survey and Index promote good budget practices and transparency around the globe. Australia’s inclusion in the Survey for the first time is appropriate given our strong commitment to good governance and a robust democracy, and our leadership in budget practices. As the global findings indicate, we should not take budget transparency and accountability for granted, even in developed countries with well-established institutions.

The Survey reveals a few gaps in the Australian budget system, which could prevent the public from assessing budget information, engaging in the budget process and holding the Government accountable for the fiscal decisions it makes. In particular, the pre-budget process, public participation and the lack of distributional information are areas in which more work could be done.

Australia has been regarded as a pioneer in budget reform, particularly since the introduction of the Charter of Budget Honesty. The OBS 2017 findings and results for Australia identify the gaps in the budget system and provide impetus for debate in Australia about further improvements to enhance budget transparency, participation and oversight.

[1] PBO submissions to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee: PBO 2018a, Partial response 1 of 2 (5 June), https://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/05%20About%20Parliament/54%20Parliamentary%20Depts/548%20Parliamentary%20Budget%20Office/Submissions/PBO%20partial%20response%20to%20written%20questions%20on%20notice%20PDF.pdf?la=en; PBO 2018b, Partial response 2 of 2 (13 June), https://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/05%20About%20Parliament/54%20Parliamentary%20Depts/548%20Parliamentary%20Budget%20Office/Publicly%20released%20costings/PBO%20final%20response%20to%20written%20questions%20on%20notice%20PDF.pdf?la=en.

[2] IBP (2018), Assessing budget credibility, https://www.internationalbudget.org/content/budget-credibility/.

[3] For example, see Alt & Lassen (2006); Alt, Lassen & Wehner (2012); Arbatli & Escolano (2015); Reinikka & Svensson (2004).

[4] Khagram, Fung & de Renzio (2013).

Further readings

Alt, JE & Lassen, DD 2006, ‘Transparency, political polarization, and political budget cycle in OECD countries’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 530-550;

Alt, JE, Lassen, DD & Wehner, J 2012, Moral hazard in an economic union: politics, economics, and fiscal gimmickry in Europe, available at SSRN, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2102334

Arbatli, E & Escolano, J 2015, ‘Fiscal transparency, fiscal performance and credit ratings’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 237-270

Arbatli, E & Mastruzzi, M 2016, How does civil society use budget information?, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

de Renzio, P & Masud, H 2011, ‘Measuring and promoting budget transparency: the Open Budget Index as a research and advocacy tool’, Governance, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 607-616.

Edelman 2017, Edelman trust barometer 2017: Executive summary, http://fipp.s3.amazonaws.com/media/documents/Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%202017_Executive%20Summary.pdf.

Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency 2015, Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, http://fiscaltransparency.net/PP_Approved_in_General_13Dec15.pdf.

Hawke, L & Wanna, J 2010, ‘Australia after budgetary reform: a lapsed pioneer or decorative architect?’, in J Wanna, L Jensen & J d Vries (eds), The reality of budgetary reforms in OECD nations: trajectories and consequences, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 65-90.

International Budget Partnership 2015, Open Budget Survey 2015, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

International Budget Partnership 2018a, Open Budget Survey 2017, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

International Budget Partnership 2018b, Australia Open Budget Survey 2017 Country Summary, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

International Budget Partnership 2018c, Australia Open Budget Survey 2017 Questionnaire, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

International Budget Partnership 2018d, New Zealand Open Budget Survey 2017 Country Summary, International Budget Partnership, Washington DC.

Khagram, S, Fung, A & de Renzio, P 2013, Open budgets: the political economy of transparency, participation, and accountability, The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Marchessault, L 2014, Public participation and the budget cycle: lessons from country examples, Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency, Washington DC.

Petrie, M & Shields, J 2010, ‘Producing a citizens’ guide to the Budget: why, what and how?’, OECD Journal on Budgeting, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1-15.

Reinikka, R & Svensson, J 2004, ‘The power of information: evidence from a newspaper campaign to reduce capture’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 3239, World Bank, Washington DC.

Seifert, J, Carlitz, R & Mondo, E 2013, ‘The Open Budget Index (OBI) as a comparative statistical tool’, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 87-101.

Stewart, M & Wong, TC 2018, Open Budget Survey 2017 Part 1: How Transparent is the Australian Budget?, Austaxpolicy: Tax and Transfer Policy Blog, 20 March 2018, Available from: http://www.austaxpolicy.com/open-budget-survey-2017-part-1-transparent-australian-budget/

Stewart, M & Wong, TC 2018, Open Budget Survey 2017 Part 2: What Can Australia Do to Improve Our Budget Process?, Austaxpolicy: Tax and Transfer Policy Blog, 2 May 2018, Available from: http://www.austaxpolicy.com/open-budget-survey-2017-part-2-budget-process/

Wilkinson, J 2018, ‘Fiscal transparency and the Parliamentary Budget Office’, Address at the launch of the Open Budget Survey for Australia, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, Canberra, 20 March, https://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/05%20About%20Parliament/54%20Parliamentary%20Depts/548%20Parliamentary%20Budget%20Office/Presentations/Fiscal%20transparency%20and%20the%20PBO%20PDF.pdf?la=en.

Recent Comments