Critics say that high earners are paying too much tax. What does the evidence say?

At the centre of this year’s federal budget and Labor’s response are competing plans for changing the income tax scale. Both start with cuts for low- and middle-income earners next financial year, and both gradually extend the reductions to higher earners over the following decade. Both involve a lighter tax bill for high earners — one more than the other — and one of them adds a cap on overall income tax collections. Each seems to have been influenced by the idea that wealthier Australians face an unusually large “tax burden.”

I want to argue that the share of tax paid by the highest earners needs to be judged in relation to the share of total income they receive — not simply their proportion of the population. The more unequal a society, the more the rich should be expected to pay in taxes. Compared to other high-income countries in the OECD, Australia’s income tax system is very progressive, yet the overall level of taxes paid by Australians — including high earners — is lower than in most.

The Coalition plan would extend the 32.5 per cent tax rate to taxpayers in the current 37 per cent bracket, beginning in the mid 2020s. It would increase the cut-in point for the highest marginal tax rate from $180,000 to $200,000. As a result, the majority of taxpayers would face the same marginal tax rate regardless of whether they earn $41,000 or $200,000 per year. Once the budget goes into surplus (which the government expects to happen in 2019–20), personal income tax revenue would be capped at 23.9 per cent of gross domestic product, or GDP.

Labor’s plan involves slightly larger cuts for lower- and middle-income groups by 2019–20, followed by further reductions for lower- and middle-income groups after that, but offers much less assistance for higher-income groups.

Both approaches have been analysed and in some cases criticised. The Grattan Institute argues that the Coalition’s plan sacrifices necessary revenue to pay for lower taxes on high-income earners, and that the richest 20 per cent of taxpayers would benefit most from the proposed flattening of the scale. Nevertheless, it says, “the plan itself doesn’t make the tax system much less progressive.”

The Centre for Social Research and Methods at the Australian National University has assessed the Coalition’s proposals and compared the government’s and the opposition’s plans. It, too, concludes that the government’s plan would lead to a modestly less progressive tax system, as would the Labor policy, but that the difference would not be large. Under the Coalition, the share of tax paid by the richest 20 per cent of households would fall from 61.2 per cent currently to 58.3 per cent in a decade; under Labor, it would fall to 59.1 per cent.

A range of other assessments of the tax plans appear on the Budget Forum website of the ANU’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute. Miranda Stewart discusses the advisability of the “cap” on Australia’s tax-to-GDP ratio, as well as the desirability of flattening the income tax scale. She concludes that “the government’s personal tax rate cuts, if fully implemented, would flatten our income tax rate structure more than ever in the past.” Bob Breunig argues that, while income tax cuts have their attractions, cutting rates without broadening the tax base poses a substantial risk to the budget’s bottom line. Teck Chi Wong points to the fact that the budget papers offer no analysis of the budget’s distributional impact. And Andrew Podger argues that both the Coalition’s and Labor’s plans complicate the income tax scale, mainly via the income-tested tax offsets they include in order to limit the cost of next year’s tax cuts.

This discussion, and other coverage of the budget, raises two main questions. What is a fair share of tax from each income group, and how much tax in total should be collected from Australians?

Fair share? It depends how you look at it

Finance minister Mathias Cormann has one answer to the first question. “We will be prioritising low- and middle-income earners when it comes to tax relief,” he said on 5 May, “but of course it’s important that the tax policy settings are appropriate overall.” He went on: “Higher-income earners overwhelmingly carry the heaviest tax burden in our economy today, and obviously, if we want to ensure that Australians are incentivised and encouraged to work hard… there’s got to be appropriate reward for effort as well.”

It’s a familiar theme. Back in 2013, the Financial Review’s Fleur Anderson was suggesting that “the middle class and the professions are staging a revolt as they find their growing share of the tax burden too hard to bear, after over a million people were made exempt from the tax system over the past ten years.” In that newspaper and elsewhere, commentators pointed to the Australian Tax Office’s tax statistics for the 2010–11 financial year, which showed that the top 5 per cent of income earners paid 34.1 per cent of net income tax and the top 25 per cent paid just over two-thirds. (The share paid by the top 5 per cent had fallen to 33.0 per cent by 2015–16.)

Just last week, also in the Financial Review, Chris Richardson of Deloitte Access Economics quoted Tax Office data showing that the top 1 per cent of earners pay 17 per cent of all personal income tax and the highest-earning 10 per cent pay 55 per cent. “That’s not what Mr and Mrs Australia think is happening…” he wrote, “mainly because the analysis you’ve been reading has talked dollars rather than shares of tax paid.”

But is “share of taxes paid” really the right way of looking at whether the tax system is fair?

Data released by the government in budget week showed that the roughly 400,000 taxpayers who earn more than $180,000 per year have a median tax bill of $85,000, which equates to an effective income tax rate of 36 per cent. The effective tax rate for those earning less than $87,001 (the point at which the second-highest marginal tax rate cuts in) was 19 per cent.

The most obvious reason why the top 1 per cent or 10 per cent pay a higher share of tax is that they receive a much higher share of taxable income. Tax Office figures show that in 2015–16 the highest 1 per cent of income taxpayers — just over 100,000 people earning $330,000 or more per year, which adds up to about $72 billion of taxable income, or an average of roughly $720,000 per taxpayer — paid 16.9 per cent of net tax but received 9.6 per cent of all taxable income. (After their income taxes, that 1 per cent of taxpayers still netted about 7.2 per cent of all after-tax income.)

So even if Australia had a completely flat tax — a single rate with no tax-free threshold — very high–income earners would still pay close to 10 per cent of all income taxes. They pay 16.0 per cent rather than 9.6 per cent because Australia has a progressive income tax scale: the rate of tax paid increases as the taxpayer’s income increases.

Rates of income tax currently begin at zero on incomes up to $18,200, with rates of 19 per cent, 32.5 per cent and 37 per cent up to $180,000 per year and 45 per cent above that level (not including the Medicare levy and the low-income tax offset). The stepped scale means that the marginal rate of income tax paid will always be higher than the average rate of income tax paid, and the most important contributor to this phenomenon is the zero rate on incomes up to $18,200. So long as we have a zero-rate range, the income tax system will be progressive.

But is it too progressive? Should the richest 1 per cent pay 17 per cent or so, as they currently do, or should they pay closer to the 10 per cent that would apply if we had a completely flat tax?

How Australia compares

Australia’s overall level of taxation is well below the average of other high-income countries in the OECD. The latest figures, from 2015, show that the ratio of total taxes to GDP in Australia was 28.2 per cent of GDP while the OECD average was 34.3 per cent. That put Australia at twenty-eighth place out of thirty-five, with most of the countries with lower tax-to-GDP ratios being lower-income countries — including Mexico, Chile and Turkey — and the outliers being the United States and Switzerland.

The composition of Australia’s taxation is also very different from that of other OECD countries, this time apart from New Zealand. Personal income taxes made up about 41 per cent of total tax revenue compared to an average of 24 per cent across the OECD, making us the second-highest in the OECD, and the share of taxes paid on corporate income was the third-highest. Australia also has relatively high taxes on property, but mainly because we have widespread home ownership. Taxes on goods and services are relatively low, mainly because the goods and services tax, or GST, ranks at thirty-three among the similar taxes in thirty-five countries.

But the main reason for our relatively low level of total taxation is that our government does not collect social security contributions, and we therefore rank equal last (with New Zealand and Denmark) on that measure. On average across OECD countries, employee and employer social security contributions account for just over a quarter of total tax revenue, or close to 8 per cent of GDP.

This is also a significant part of the reason why income taxes account for so high a proportion of total revenue in Australia. Social security contributions are very similar to income taxes, however, with employee contributions usually being deducted at the same time as income taxes in the countries that collect them. Like income taxes, they are generally counted as direct taxes on households or individuals. Employer social security contributions, by contrast, are usually treated as if they were indirect taxes, even though they too are paid directly to government and are commonly regarded as effectively being paid by employees through lower wages.

It is sometimes suggested that tax comparisons should take account of the superannuation guarantee paid by employers in Australia. As Treasury argued in its 2015 Re:think tax discussion paper, “Australia’s compulsory superannuation system — the superannuation guarantee — is sometimes equated to a social security tax. However, as it is paid directly into private superannuation accounts (currently set at 9.5 per cent of an employee’s ordinary time earnings) rather than to the government, it does not meet the definition of a tax.” It’s also important to remember that twelve other OECD countries also have either mandatory occupational or private pensions, or schemes that are close to mandatory under industrial agreements.

But the lack of social security contributions still gives a clue as to why Australia has a relatively low level of overall taxation.

Compared to other rich countries, Australia is well down the OECD rankings in terms of government spending and taxation, with the third-lowest level of government spending and the fourth-lowest level of overall government revenue. And a major reason for Australia’s low overall level of spending is that our outlay on social security is among the lowest of the OECD countries. Total government spending as a proportion of GDP in Australia is about 78 per cent of the OECD average and spending on areas other than social protection is about 90 per cent, but spending on social security benefits is only about 70 per cent of the OECD average.

Tax revenues in Australia are about six percentage points of GDP below the OECD average, and our total level of spending is eight percentage points of GDP below the average, with our social security spending being four percentage points of GDP below average. In this sense, our low social security spending accounts for nearly half of our overall lower spending and consequently our lower taxes.

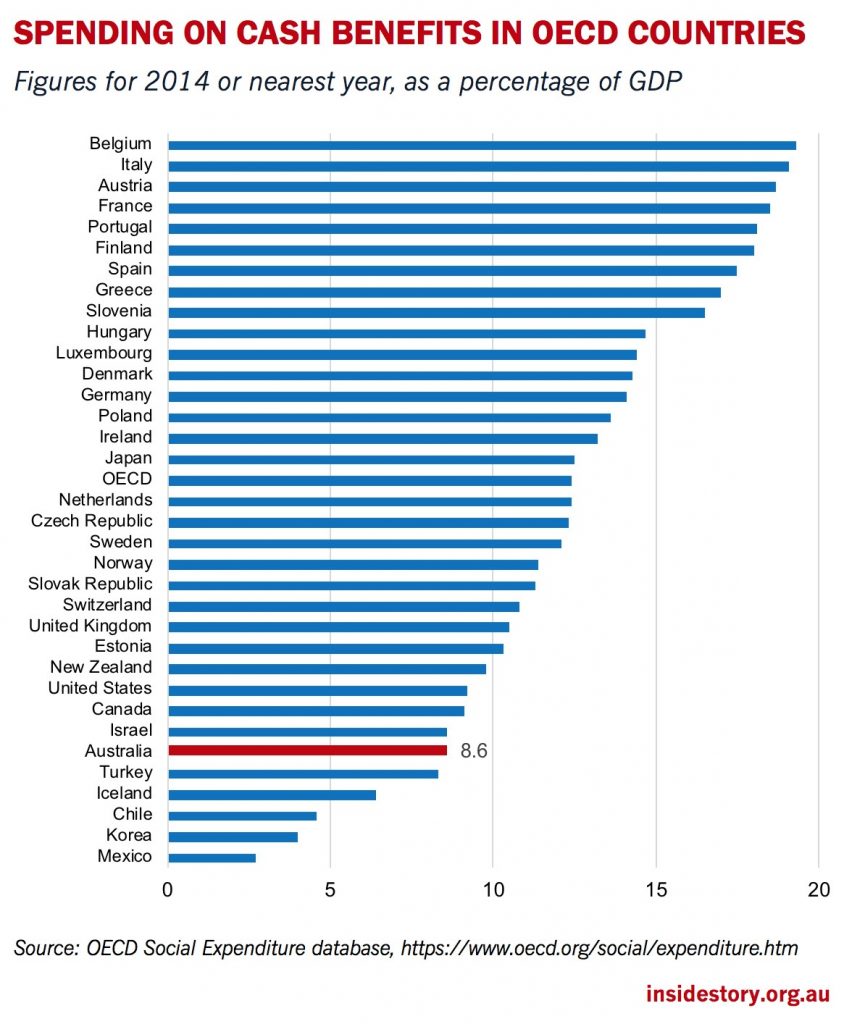

As the chart shows, spending on cash benefits in 2014 was 8.6 per cent of GDP, the sixth-lowest level of thirty-five OECD countries. Why so low? Our social security system differs markedly from those in most other countries. In Europe, the United States and Japan, as we’ve seen, social security is financed by contributions from employers and employees, with benefits related to past earnings; this means that higher-income workers receive more generous benefits if they become unemployed or disabled, or when they retire.

As the chart shows, spending on cash benefits in 2014 was 8.6 per cent of GDP, the sixth-lowest level of thirty-five OECD countries. Why so low? Our social security system differs markedly from those in most other countries. In Europe, the United States and Japan, as we’ve seen, social security is financed by contributions from employers and employees, with benefits related to past earnings; this means that higher-income workers receive more generous benefits if they become unemployed or disabled, or when they retire.

Australia makes flat-rate payments, financed from general taxation revenue, that are income-tested or asset-tested. The rationale for this approach is that it reduces poverty more efficiently by concentrating the available resources on the poor and minimises adverse incentives by limiting the overall level of spending and taxes.

In fact, Australia relies more heavily on income-testing than any other OECD members. OECD figures show that nearly 80 per cent of Australian cash-benefit spending is income-tested, compared to just over half in Canada, 37 per cent in New Zealand, around 26 per cent in Britain and the United States, and less than 10 per cent in most European countries. (These figures include spending on state government workers’ compensation schemes and federal and state public service pensions, which are not income-tested.)

As a result, lower-income earners receive a bigger share of benefits than in any other OECD country. The poorest 20 per cent of the Australian population receives nearly 42 per cent of all social security spending; the richest 20 per cent receives around 3 per cent. In other words, the poorest fifth receives twelve times as much in social benefits as the richest fifth. In the United States, the poorest get about one and a half times as much as the richest. At the furthest extreme are countries like Greece, where the rich are paid twice as much in benefits as the poorest 20 per cent, and Mexico and Turkey, where the rich receive an extraordinary five to ten times as much as the poor.

In economic terms, income-testing can be seen as analogous to taxing. Social security recipients lose between 40 and 60 per cent of any income earned above “free areas” (currently between $52 and $84 per week for single people receiving allowances or pensions). When these withdrawal rates overlap with the income tax system, recipients can face very high effective marginal tax rates, created by the combination of income tax paid and benefits withdrawn. They might lose 70 per cent or more of any earnings, a reduction greater than the top marginal income tax rate.

Income-testing also affects the way the Australian tax system is structured, and particularly its treatment of low incomes generally. As we’ll see, this has important implications for the overall progressivity of the tax scale.

Distributing taxes

The distribution of taxes across countries or across time can be compared in a number of ways, none of them perfect but each throwing some light on the question. Using administrative data from the Australian Tax Office and its overseas equivalents — as the finance minister and many newspaper articles do — can be misleading because the reported statistics are not always directly comparable. Complicating the picture further is the fact that income tax is paid by different proportions of the population in different countries (in Australia it’s around half of all adults, or roughly ten million individuals).

We can calculate the taxes individuals must pay at different income levels by using the tax schedules of each country. The OECD publishes estimates of these statutory tax liabilities at different wage levels in its series Taxing Wages. It includes calculations of the income tax liabilities and the employee’s social security contributions payable by individuals at 67 per cent, 100 per cent and 167 per cent of the average wage, and by families with and without children, using different combinations of earnings by each partner.

According to these data, Australia ranked twenty-fourth out of thirty-five countries in 2017 in terms of the taxes paid by a worker at 67 per cent of the average wage, twentieth for a worker at 167 per cent of the average wage, and twenty-eighth according to the level of total tax revenue, suggesting that Australia is more progressive than average.

While these figures are extremely useful for understanding how the tax systems work in each country, in Australia’s case they don’t include most taxpayers — for example, 67 per cent of the average wage is close to the median income taxpayer, while 167 per cent of the average wage is close to the ninety-second percentile of the distribution of taxpayers. Comparisons based on this source, at least for Australia, leave out the bottom half of taxpayers and most of the richest 10 per cent.

A related OECD series, Benefits and Wages, provides more detailed spreadsheets of the income tax liabilities and social security contributions of employees in different family types at single percentiles of the average wage, from zero to 200 per cent. They include families receiving social security benefits but don’t cover the richest 3 per cent of Australian taxpayers, who pay roughly 30 per cent of net taxes.

To compare progressivity across countries we also need to know the share of the population at different income levels. For this purpose, the best source of data is household income surveys — the type of data that the Centre for Social Research and Methods at the ANU used in its analysis of the potential impact of the federal budget. These data are more comprehensive because they cover the entire population, including people who don’t pay income tax, and they combine the incomes of all members of a household and then adjust for the number of people who live in the household.

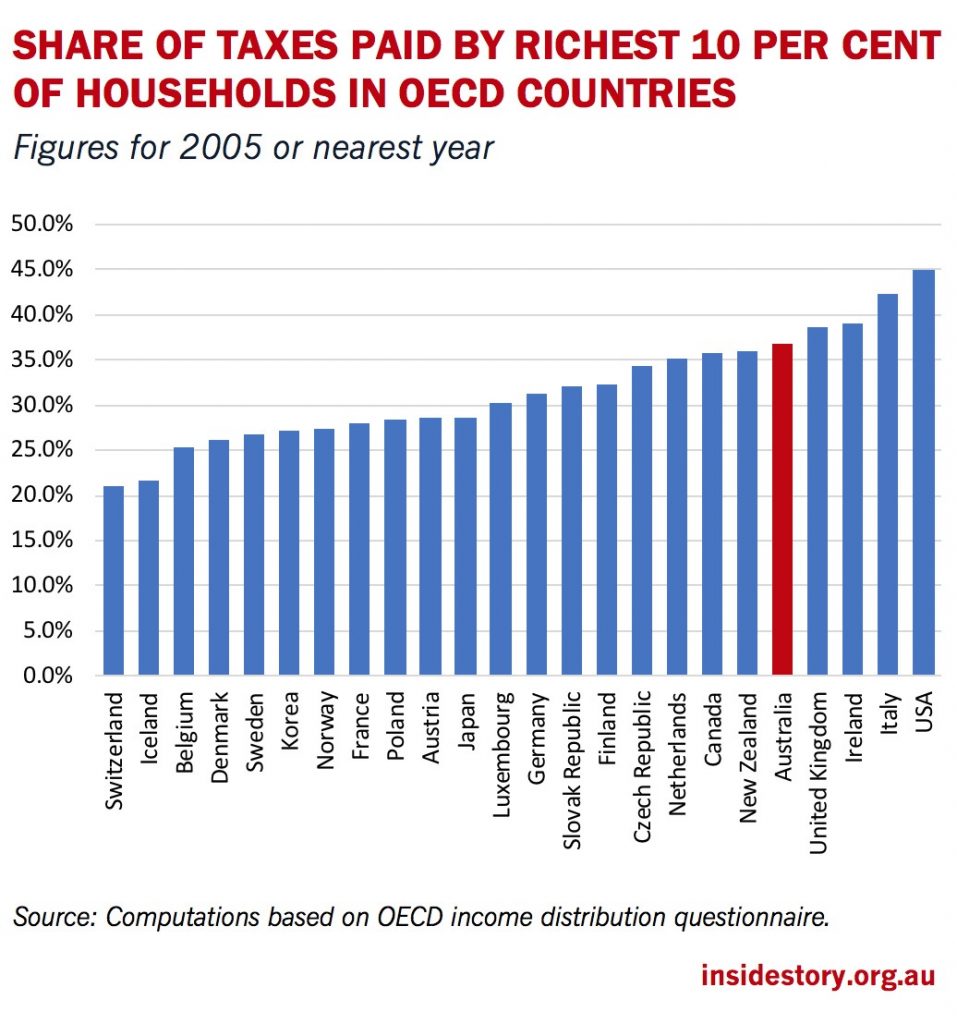

The most recent analysis of the progressivity of household taxes by the OECD was in Growing Unequal?, a report published in 2008. The chart below shows the share of direct taxes (income tax and employee social security contributions) paid by the richest 10 per cent of households in OECD countries around 2005. The rather surprising result of this analysis is that the share of direct taxes paid by the richest is highest in the United States — a finding that provoked a good deal of controversy. (Disclosure: I wrote the chapter with this finding in the OECD report, although the calculations were made by other colleagues at the OECD.)

After the United States, the distribution of taxation tends to be most progressive in the other English-speaking countries — Ireland, Australia, Britain, New Zealand and Canada — and in Italy, followed by the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Germany. Taxes tend to be least progressive in the Nordic countries and in France and Switzerland.

Part of the explanation for the US finding is that, as we’ve seen, the progressivity of the tax system partly depends on the level of inequality of taxable income. In other words — all other things being equal — the greater the share of income received by the rich, the greater their share of taxes paid.

Part of the explanation for the US finding is that, as we’ve seen, the progressivity of the tax system partly depends on the level of inequality of taxable income. In other words — all other things being equal — the greater the share of income received by the rich, the greater their share of taxes paid.

Among high-income OECD countries, the United States ranks third-highest according to income received by the richest 10 per cent of households (after Italy and Poland). The richest 10 per cent of American households capture 33.5 per cent of income, compared to an OECD average of 28.4 per cent and 28.6 per cent in Australia.

One way of adjusting for this inequality is simply to divide the share of taxes paid by the share of income. On this measure, the United States still has the most progressive system of direct taxes in the OECD: the richest 10 per cent pay a share of taxes that is 35 per cent higher than their share of income. But Australia moves from being ranked the fifth most progressive to the second most progressive, with the richest 10 per cent paying a share of taxes that is 29 per cent higher than their share of income.

Other OECD measures reach very similar conclusions. One is the concentration coefficient, which is calculated in the same way as the better-known Gini coefficient, but with taxes ranked by the share of income held by different income groups. As Growing Unequal? shows (see page 107), dividing the concentration coefficient of taxes by the concentration coefficient of income results in Ireland having the most progressive direct tax system in the OECD, with the United States and Australia coming in at second and third positions respectively.

Why is the Australian tax system more progressive?

The progressivity of the tax system does not tell us how high the level of taxes is; a more progressive tax system is simply one where the level of taxes increases with income at a more rapid rate than in a less progressive tax system. One of the main reasons why Australia has a more progressive system than most other high-income countries is not that high-income groups pay high rates of tax but that low-income groups in Australia pay very low rates of tax.

Growing Unequal? (page 116) gives comparative figures for around 2005. It shows that the poorest 20 per cent of Australian households paid only 0.8 per cent of all direct taxes, compared to an average for twenty-three OECD countries of 4.2 per cent. This was the lowest share of all OECD countries, and far short of up to 6 per cent in Denmark and Sweden and 12 per cent in Switzerland. The taxes paid by the poorest 20 per cent of Australian households were 0.2 per cent of total household disposable income, the equal lowest in the OECD.

On average for all Australian households, direct taxes were 23.4 per cent of equivalent household disposable income, compared to an average among twenty-three comparable OECD countries of 28.3 per cent, placing us sixth-lowest in the OECD, a ranking similar to that found when total taxes are expressed as a percentage of GDP.

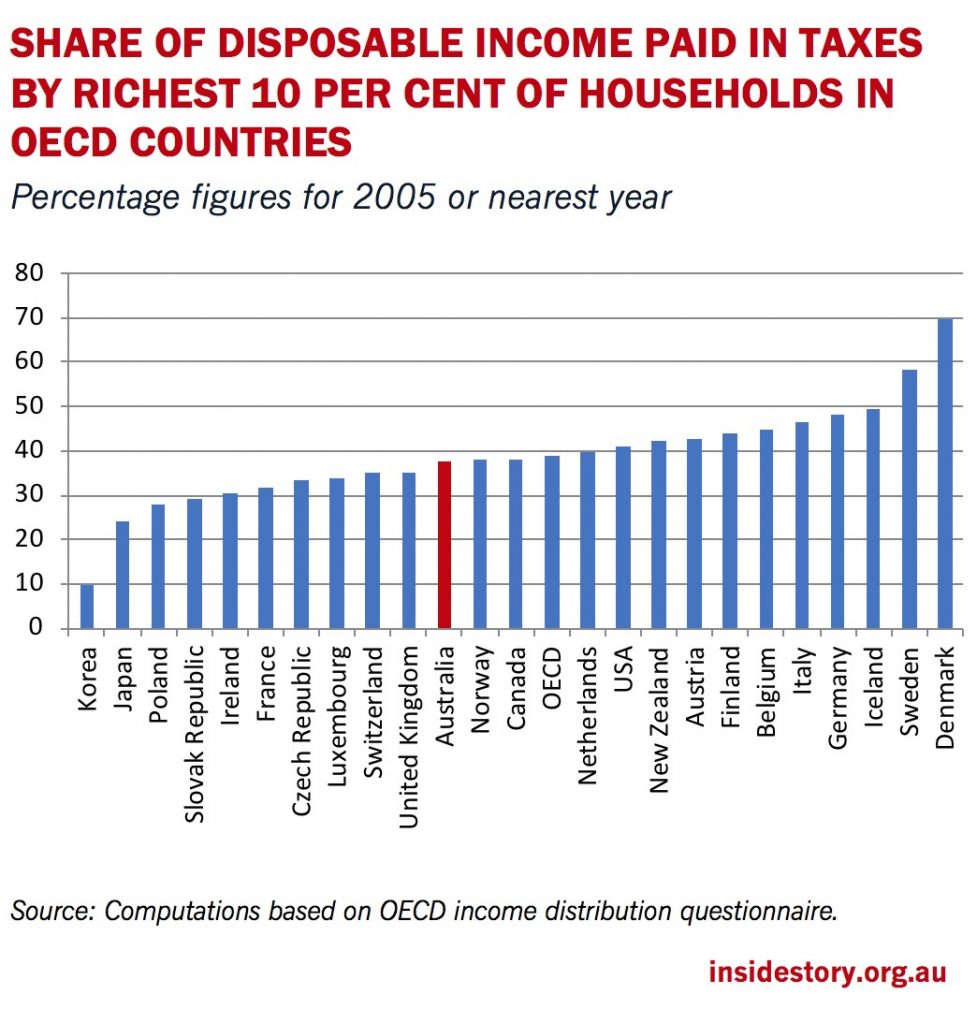

While the richest households in Australia pay one of the highest shares of direct taxes, this does not mean that the taxes paid by the rich are higher than in other countries. The chart below shows the taxes paid by the richest 10 per cent as a share of their disposable income. When people talk of the “tax burden,” this is what they are likely to be most concerned with — how much of my income do I pay in taxes?

The chart below shows that the richest 10 per cent of households in Australia paid 37.8 per cent of their disposable income in taxes, just below the OECD average of 38.8 per cent, a little higher than in Britain but lower than in Canada, the United States or New Zealand — and very much lower than in Denmark, Sweden and Iceland.

It is notable that in some of the countries where the rich pay a low share of total taxes, the share of their income paid in taxes is extremely high. The most striking example is Denmark, where the richest 10 per cent pay not much more than 25 per cent of direct taxes, but pay tax at an average rate of 70 per cent.

It is notable that in some of the countries where the rich pay a low share of total taxes, the share of their income paid in taxes is extremely high. The most striking example is Denmark, where the richest 10 per cent pay not much more than 25 per cent of direct taxes, but pay tax at an average rate of 70 per cent.

Put another way, the poorest 10 per cent of Danish households pay 2.5 per cent of household taxes and the richest 10 per cent pay 26.2 per cent of taxes, a ratio of about 10.5 to one. In Australia the poorest 10 per cent pay 0.2 per cent of all taxes and the richest 10 per cent pay 36.8 per cent of household taxes, a ratio of 184 to one. The progressivity of the Australian tax system is much greater than the progressivity of the Danish system, but mainly due, as we’ve seen, to the very low share of taxes paid by low-income Australian households.

The reason why low-income Australians pay very low taxes reflects the nature of our social security system. In many European countries social security benefits are a high proportion of previous earnings, while in Nordic countries, where they also tend to be high, they involve a mix of more universal provisions and earnings-related provisions. In these countries, it makes sense to tax social security benefits as if they were ordinary income because they replace a large share of previous income.

In Australia, where benefits are more modest and flat-rate, it makes little sense to tax them highly. If benefits are intended to alleviate poverty, then imposing higher levels of taxation on them would imply that we were paying people too much. Instead, we ensure that people receiving benefits are not liable for income tax on their basic payments through the combination of a high basic tax threshold, the low-income tax offset (which replaced earlier special tax offsets for pensioners and beneficiaries) and the seniors and pensioners tax offset, as well as the exemption from tax of family payments.

Two ways to target welfare

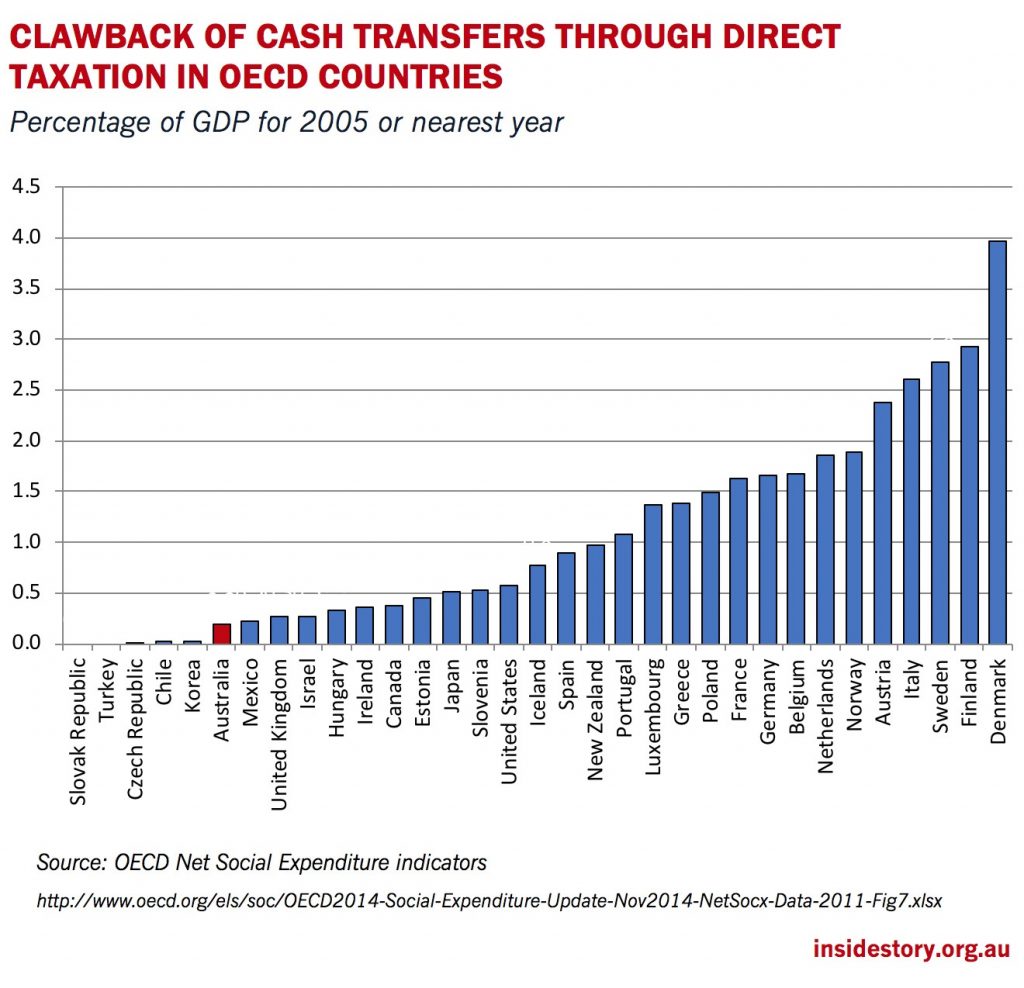

A corollary of the fact that our benefit system targets the poor more than any other country’s is that our tax system claws back less of our spending.

The chart below shows OECD estimates of the proportion of direct taxes (income taxes plus employee social security contributions) that are paid out of cash transfers. In Australia, direct tax payments made from social security benefits amount to only 0.2 per cent of GDP, with the only countries with lower levels of direct tax paid out of benefits being lower-income countries. At the other extreme, high-spending Nordic welfare states collect direct taxes on benefits of close to 3 per cent of GDP, or in the case of Denmark around 4 per cent of GDP.

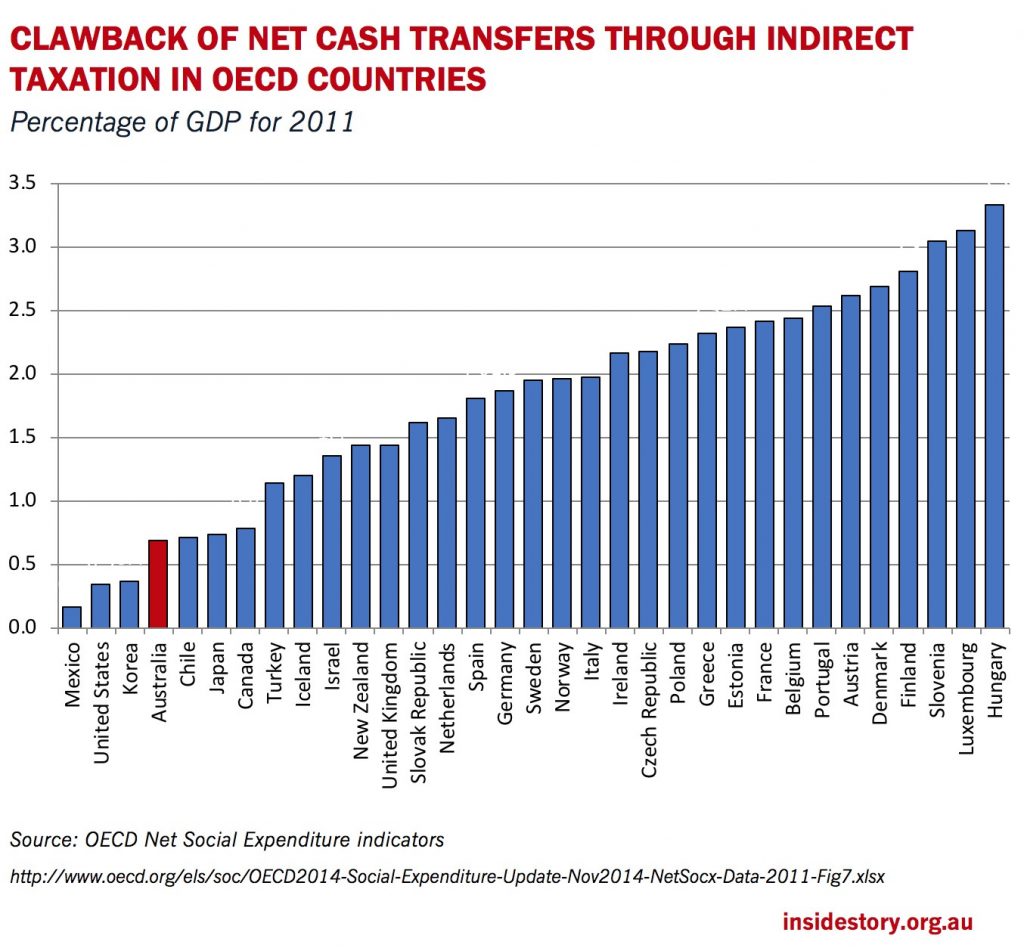

The next chart shows OECD estimates of clawbacks through indirect taxes, including the GST in Australia and value-added taxes in Europe. Again, Australia has one of the lowest levels in the OECD, at around 0.7 per cent of GDP, compared to 2.5 per cent or more in a range of Nordic and other European welfare states.

The next chart shows OECD estimates of clawbacks through indirect taxes, including the GST in Australia and value-added taxes in Europe. Again, Australia has one of the lowest levels in the OECD, at around 0.7 per cent of GDP, compared to 2.5 per cent or more in a range of Nordic and other European welfare states.

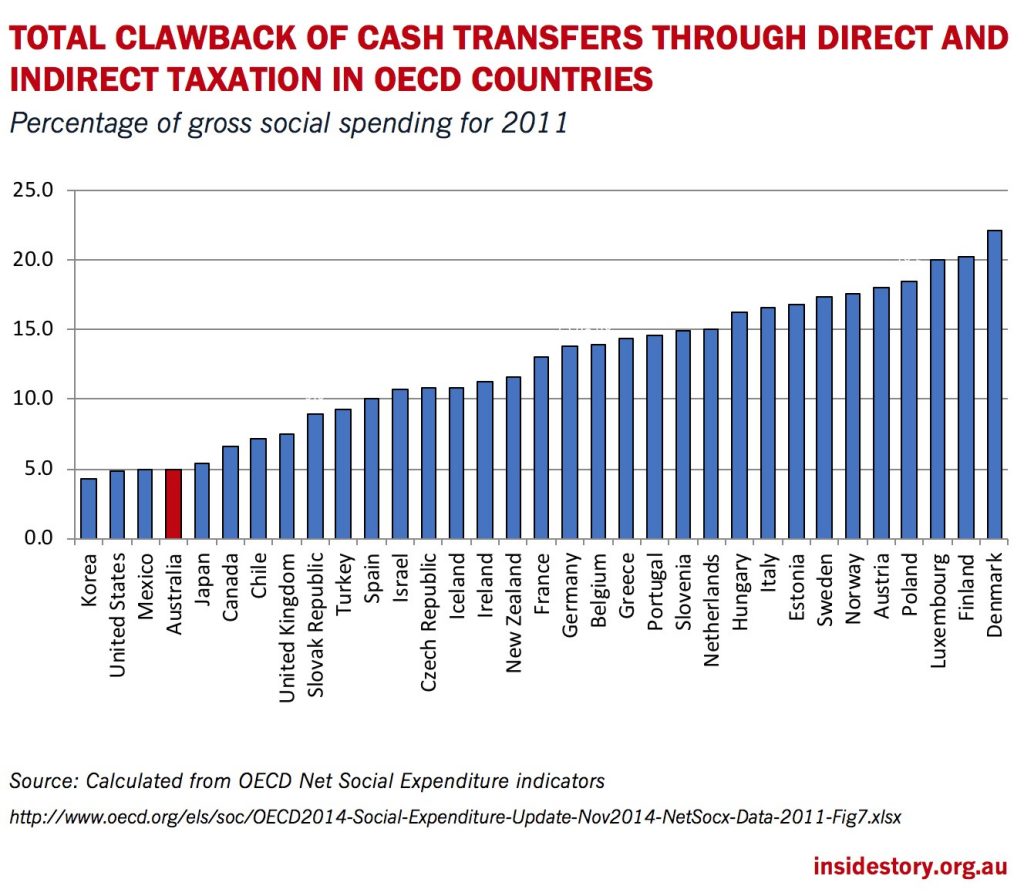

The final of these charts shows the combined effects of direct and indirect taxation on the level of social spending, expressed as a percentage of gross social spending. Australia had the equal third-lowest level of tax clawback in the OECD in 2011, at 4.9 per cent of social spending. At the other extreme, in Luxembourg, Finland and Denmark, 20 per cent of a much higher level of spending is clawed back.

The final of these charts shows the combined effects of direct and indirect taxation on the level of social spending, expressed as a percentage of gross social spending. Australia had the equal third-lowest level of tax clawback in the OECD in 2011, at 4.9 per cent of social spending. At the other extreme, in Luxembourg, Finland and Denmark, 20 per cent of a much higher level of spending is clawed back.

The fact that Australia overall has the most income-tested social security system of all OECD countries is linked to the fact that we tax cash benefits less than most. Income-testing is a way of taxing in advance rather than clawing back spending through the tax system after payments have been made. Each can be regarded as differing ways of seeking to achieve rather similar goals.

The fact that Australia overall has the most income-tested social security system of all OECD countries is linked to the fact that we tax cash benefits less than most. Income-testing is a way of taxing in advance rather than clawing back spending through the tax system after payments have been made. Each can be regarded as differing ways of seeking to achieve rather similar goals.

Is that the whole story?

As we’ve seen, the progressivity of the tax system is usually measured according to the difference between the tax rates paid by high-income and low-income groups. Australia’s system is highly progressive not because we tax the rich heavily but mainly because we tax the poor very lightly. This is primarily the result of a relatively high tax threshold, which benefits all taxpayers by reducing the average rates of tax they pay to well below their marginal rate. The combination of our low level of social security spending and low tax on social security benefits results in lower levels of average taxation overall.

But the conclusion that Australia has a relatively progressive tax system can be challenged in several ways. First, not all high-income earners actually pay the taxes that would normally be assumed to apply to their circumstances. As the Age’s economics editor Peter Martin has pointed out, forty-eight millionaires paid no tax at all in 2017, according to what were then the latest Tax Office statistics (compared to seventy-five reported in 2014, fifty-five in 2015 and fifty-six in a 2016 article).

These examples certainly mean that the income tax system is not as progressive as it is intended, but they don’t mean the system is not progressive overall. The forty-eight who paid no tax in the 2017 report, for instance, had an average pre-tax income of close to $2.5 million dollars, or a combined $120 million — about one-fifth of 1 per cent of the $70 billion-plus declared taxable income of the richest 1 per cent in 2015–16. These cases might show that effective progressivity is less than the statutory progressivity of the tax scale, but the Tax Office data show that this group still pays a high share of total income tax.

More serious is the second objection, which hinges on the issue of money held in tax havens. In The Hidden Wealth of Nations, economist Gabriel Zucman estimates that assets in tax havens amount to around 8 per cent of global financial assets. (In Russia’s case, the figure is 75 per cent.) The release of the Panama Papers in 2016 prompted the Tax Office to investigate 800 “high net-wealth Australians,” according to the Financial Review, although the scale of their offshore holdings was not stated.

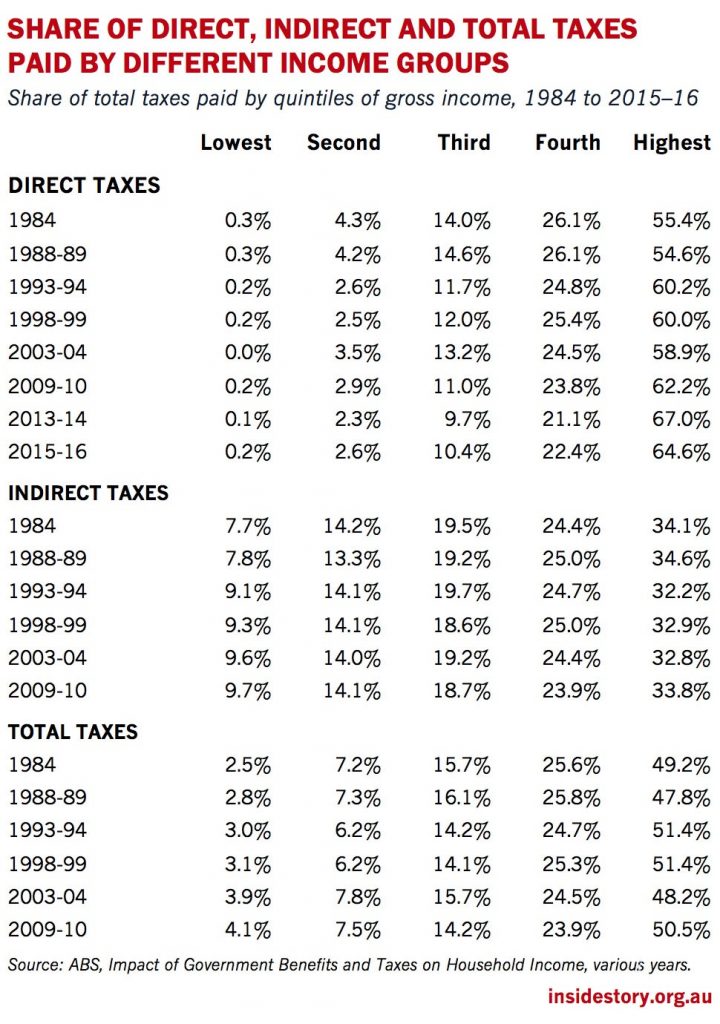

Third, it’s important to remember that income tax and other direct taxes are not the only taxes paid by Australians. The table below shows estimates of the share of direct and indirect taxes paid by different income groups in Australia between 1984 and 2015–16 in the case of direct taxes, though only up to 2009–10 for indirect taxes and total taxes. (The Australian Bureau of Statistics will publish more up-to-date estimates of indirect taxes and total taxes, for 2015–16, within the next twelve months.)

The table ranks households by their gross income without adjusting for household size, because these data are readily available from the 1980s onwards and are less affected by definitional changes over time. The share of direct taxes paid by the richest 20 per cent has gone up over time, although it was not quite as high in 2015–16 as two years earlier. This partly reflects a higher share of income going to the rich between the 1980s and the mid 1990s.

Although the share of indirect taxes paid by the rich has been broadly stable, the poorest 20 per cent of households pay a much higher share of these taxes than they pay of income taxes, most recently close to 10 per cent, up from around 8 per cent in the 1980s.

The share of total taxes paid by the richest 20 per cent is very similar to their share of income. In 2003–04, the richest 20 per cent of Australian households received 49.8 per cent of private income before taxes and paid 48.2 per cent of total taxes. On this measure, total direct and indirect taxes are substantially less progressive than direct taxes alone — in fact, they are closer to proportional than progressive.

The share of total taxes paid by the richest 20 per cent is very similar to their share of income. In 2003–04, the richest 20 per cent of Australian households received 49.8 per cent of private income before taxes and paid 48.2 per cent of total taxes. On this measure, total direct and indirect taxes are substantially less progressive than direct taxes alone — in fact, they are closer to proportional than progressive.

It’s therefore possible to argue that the reduction in income inequality achieved by the Australian tax–transfer system is primarily brought about on the spending side of the equation (although, of course, that spending is funded by tax revenue).

That’s not to say that governments haven’t been conscious of the impact of indirect taxes on overall progressivity. When the GST was introduced in 2000 it was accompanied by income tax cuts designed to compensate low-income taxpayers. Effective income tax thresholds were increased, making that part of the system more progressive, even while the overall system actually became less progressive.

As the table above shows, between the 1998–99 and 2003–04 surveys the overall tax system became less progressive because of the increased share of much-less-progressive indirect taxes: in fact, the ratio of total taxes paid by the richest 20 per cent to the taxes paid by the poorest 20 per cent was cut from seventeen-to-one to a little more than twelve-to-one between 1998–99 and 2003–04. In other words, the complaint that income taxes have become more progressive ignores the fact that this partly reflects regressive changes in other parts of the tax system.

While indirect taxes make the Australian tax system much less progressive, they are unlikely to change Australian rankings in international comparisons. The level and coverage of value-added taxes in most other OECD countries are much higher than for the GST in Australia. New Zealand’s GST rate, for instance, is 15 per cent, and it covers a broader range of purchases than Australia’s; many European countries have value-added tax rates of 20 per cent or higher and also have a broader coverage than here.

Speed limiting the future

While much of the discussion of the federal budget tax proposals has focused on the “fairness” of different plans, an important element is the proposed federal tax cap of 23.9 per cent of GDP. This is based on an average of tax levels from 2000–01 to 2007–08, a benchmark that doesn’t make much sense. As Ross Gittins observes, “in none of those eight years did the [tax-to-GDP] ratio actually hit 23.9 per cent. Rather, it ranged between 23.3 per cent and 24.3 per cent. Indeed, it exceeded 23.9 per cent in five of the eight years.” Setting the average as a cap and allowing some years to be below this level is actually equivalent to reducing the future average tax rate. Moreover, as Gittins points out, the cap would require tax cuts when the economy is doing strongly and tax revenues are rising — that is, tax cuts would be hazardously pro-cyclical.

In the longer run, as Miranda Stewart argues, “It seems likely we will need to increase our tax level somewhat in future, to ensure fairness and sufficient investment in Australia, in a changing and risky world with an ageing population. At least, this is a debate we should have.”

Mike Keating, a former head of the finance and prime minister’s departments, argues in Pearls and Irritations that “it will be necessary to increase the ratio of government revenue to GDP by three percentage points over the next three decades. In our view, that is not much to maintain an inclusive society, and it would still leave Australia as a low tax country.”

Reinforcing the point, he notes that both “the Committee for Economic Development of Australia and the Grattan Institute have independently concluded that budget repair will require action to be taken on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget, and that most of the proposed fiscal adjustment will have to come from increased revenue. Indeed, the Grattan Institute is quite adamant that ‘governments will not be able to restore budgets without also boosting revenues.’”

The 2015 Intergenerational Report projected that government spending on healthcare will increase from 4.2 per cent to 5.7 per cent of GDP by 2055, on age pensions from 2.9 per cent to 3.6 per cent of GDP, and on aged care from 0.9 per cent to 2.1 per cent of GDP. Spending on other payments to individuals, by contrast, would fall from 4.5 to 3.4 per cent of GDP, with much of this being accounted for by a fall in family payments.

Like the architects of the proposed tax cap, the Intergenerational Report assumed that the federal tax-to-GDP ratio stays at 23.9 per cent of GDP for the whole period. With stable tax revenues and rising age-related spending, budget deficits would persist over this forty-year period, the cash deficit reaching about 6 per cent of GDP in 2054–55 and net debt rising from 15.2 per cent to 60 per cent of GDP.

At the time, I pointed out that the report’s assumed continuation of legislated policies would mean that payments to the unemployed and families would nearly halve relative to projected future wage levels. Unemployment would stay fairly constant, but with those who experience it becoming increasingly impoverished. Family Tax Benefit Part A for the lowest-income families would nearly halve relative to wages by the middle of the century, leading to a significant increase in the depth of child poverty.

If we assume that the age-related spending projections are accurate and we do not want to see the deep impoverishment of future low-income working-age Australians — or at least we believe that deep poverty will be unacceptable in a significantly richer future Australia — then we certainly do need to debate how to increase future tax revenues. (We might also want to increase foreign aid, which has been cut for five years running, and in an uncertain international environment it may be necessary to increase defence spending.)

The public seems to agree. In the latest Per Capita Tax Survey, around 87 per cent of more than 1500 respondents favoured increased spending on health, nearly 78 per cent favoured increased spending on education, and 55 per cent wanted more spent on social security. Around 44 per cent believed they paid around the right amount of tax and 43 per cent thought they paid too much. Two-thirds believed high-income earners pay too little tax.

Is increased progressivity of the tax scale the answer? Those who question whether high-income groups pay an “unfairly high” share of tax are likely to say no, yet the Per Capita survey suggests this is where a majority of Australians think the answer lies.

As we’ve seen, though, high-income groups in Australia do not face particularly high average tax rates by international standards. It is certainly possible to increase the effective progressivity of the tax system by broadening the tax base and addressing tax expenditures and concessions like negative gearing.

It is particularly important to remember that we should look at the whole system of taxes and transfers and other social spending when setting policy directions. The progressivity of just one part of the overall system of taxes and transfers should not be the only factor taken into account in determining whether we have a fair distribution of taxes and spending.

This lesson was underlined by social policy analysts Walter Korpi and Joakim Palme in their 1998 article, “The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality.” They show that the main determinant of the degree of redistribution achieved by Nordic welfare states is the amount of revenue they collect, even though their tax and welfare systems are not as progressive as Australia’s. The lesson of international comparisons is that it is necessary to balance progressivity with the collection of the revenue needed for social spending. The federal budget’s tax measures can scarcely be seen as a step in the right direction.

This article was first published by Inside Story on 1 June 2018.

Hi Peter, Some interesting data, but like comparisons across OECD countries it’s fraught with inconsistencies. I would like to know within the top 10% of income earners and households.what % receive income via trusts.

Regards

Wayne