On 1 July, the age of eligibility for the Age Pension in Australia increased from 66.5 years to 67 years, completing a series of increases that started in 2017. This legislation was originally enacted in 2009 by the Rudd Government.

Interestingly, this increase has been achieved with little protest, which stands in stark contrast to the demonstrations and riots that unfolded in France earlier this year. The Macron government faced significant opposition when it proposed and passed laws to increase the pension age from 62 to 64 years.

Pension reform has a long and controversial history in France. In 1995, attempts to change the eligibility age for public sector workers resulted in weeks of general strikes and the largest demonstrations since 1968, ultimately resulting in a government climbdown. Mass protests erupted again in 2003 in response to a proposal to extend the contribution period to 40 years for public workers. In 2010, the retirement age was increased from 60 to 62 under the Sarkozy government, which also faced nationwide strikes and demonstrations.

These demonstrations illustrate the challenges associated with cutting popular social programs. As US political scientist Paul Pierson argued in 1996, “there is a profound difference between extending benefits to large numbers of people [as had been the case in the period of welfare state expansion between the 1940s and the 1970s] and taking benefits away”.

One of the barriers to cutting social programs results from the interest‐group structure created by those programs. German sociologist Claus Offe coined the phrase ‘policy‐takers’ to describe political groups created by the existence of a policy, driven by their shared interest in perpetuating the policy.

Examples of policy‐takers include military veterans and senior citizens, who have formed groups to lobby for improved government benefits. In the case of the United States, the Social Security system has often been labelled as the “third rail” – touch it and you die – in recognition of the formidable strength of the interest groups supporting it.

Pierson saw policy‐takers as possibly the most significant bulwark of the welfare state against potential programme cutters. Simply put, the welfare state has generated its own political support base.

But interest groups can be formed not only by groups of voters, because social programs can strongly influence what Joseph Conrad (in a different but possibly related context) referred to as “material interests” within a society.

How pension systems compare

Retirement pensions usually represent one of the largest spending programs in any rich country. In Australia, nearly half of our spending on social security cash benefits is allocated to age pensioners.

The OECD report on Pensions at a Glance, published biennially, provides comprehensive information on public pension schemes in high-income countries. The most recent edition of the report was published in 2021.

Apart from a wide range of analytical comparisons, the report also includes specific descriptions of the pension systems in each country.

Public pension spending in France amounts to 13.6% of GDP, in stark contrast to Australia’s 4.0%. Spending on retirement pensions accounts for nearly two-thirds of France’s social security spending.

This disparity partly stems from the fact that France possesses a much older age structure than Australia. The French population aged 65 years and above accounts for 37% of the working-age population, compared to 27% of the Australian working-age population.

It also reflects the fact that payment levels are generally much higher in France than in Australia.

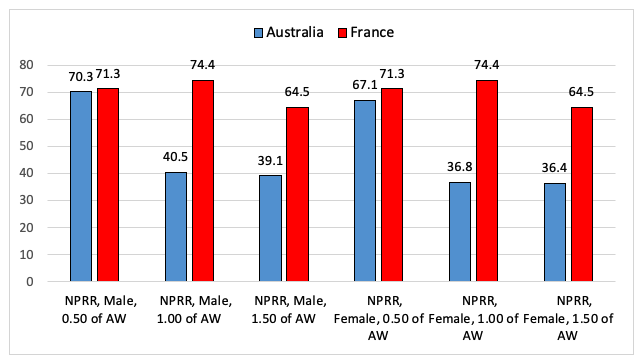

Chart 1 displays the OECD estimates of net pension replacement rates, which indicate the percentage of previous earnings that a worker receives after retirement. These rates depend on the individual’s earnings level, gender and the number of years of contributions they pay.

Chart 1: Net pension replacement rates (NPRR) for male and female workers at different earnings levels, % of previous earnings

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance, 2021. Note: AW refers to average wage.

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance, 2021. Note: AW refers to average wage.

These results are “forward looking” as they are calculated based on what a worker would be entitled to if they spent their entire working lives, starting from age 22 and continuing until the country-specific normal retirement age, under the system that applied in 2020.

In the case of Australia, they include both the effects of the Age Pension and the superannuation received through the Superannuation Guarantee.

Under the previous pension system in France, when an average French worker retired, they could expect to receive a pension amounting to approximately three-quarters of their previous earnings. A higher-paid worker would receive nearly two-thirds of their previous earnings, while a lower-paid worker would receive just over 71% of their previous earnings.

A comparable low-paid Australian worker is calculated to receive just over 70% of their previous earnings, a figure that closely aligns with the French level. This similarity arises from Australia’s income-tested system, which targets benefits towards lower income-groups.

However, in Australia, average earners and higher-paid workers receive considerably less than their French counterparts, amounting to around 40% of their previous earnings, even when including superannuation.

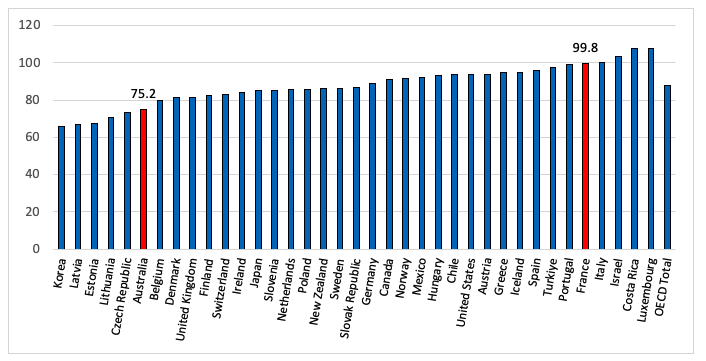

Chart 2 shows the average income after tax of households headed by individuals aged 65 years and over, compared to the average income of the total population in 2018. Therefore, it represents the income that households were recently receiving, rather than what they would receive looking ahead.

Chart 2: Average income of retirement age households as % of working-age households, OECD countries, 2018 or nearest year

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance, 2021.

On average across the OECD, individuals aged 65 and over receive incomes equivalent to 88% of the income of the total population. In Australia, older households have average incomes after tax (adjusted for household size) that amount to 75% of the population average. The only countries with lower ratios are Korea and four Eastern European countries.

In contrast, in France, the average disposable incomes of households in retirement age were nearly equal to 100% of the population average, ranking as the fifth highest among OECD countries at the time.

(Several technical points should be made to explain some of these differences: Korea: The large income gap between retirement and working years is attributed to its high rates of economic growth and a very high life expectancy. This means that there are people who retired from work 20 or more years earlier, when wages were much lower in real terms. Luxembourg: Retirees have very high incomes due to the presence of a large number of temporary migrant workers who earn lower wages. These workers often return to their home countries in other parts of Europe when they retire. Lower-income countries: In countries such as Costa Rica, Mexico and Türkiye, pension coverage applies only to highly paid workers in the formal economy.)

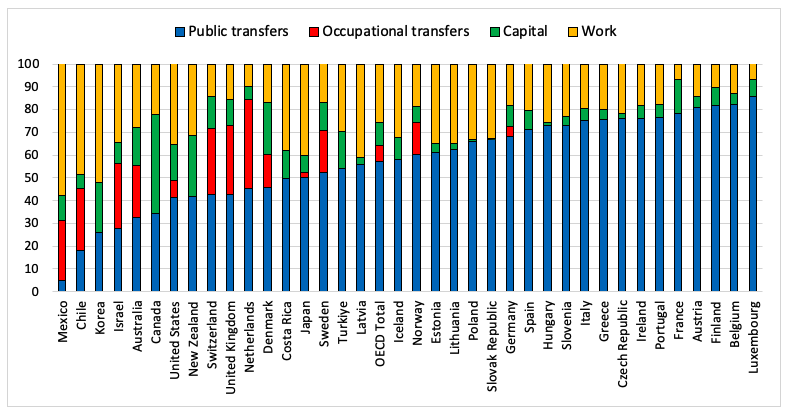

Chart 3: Public pensions as % of the average income of retirement age households, OECD countries, 2018 or nearest year

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance , 2021.

Chart 3 shows the composition of disposable incomes for households over the pension age in 2018. In Australia, public pensions accounted for only one-third of the household disposable incomes of individuals over 65 years, placing it on the lower end of OECD countries. In contrast, public pensions in France constituted nearly 80% of the total incomes of the retirement age population.

The significance of the pension system for the French population becomes even more apparent when considering the number of individuals receiving retirement pensions. The OECD Social Benefit Recipients database reveals that in 2018, there were 3.9 million Australians aged 65 years and over, of which 2.6 million (or 66%) were receiving an Age Pension or other retirement income support payment. In France, there were 13.3 million people over the age of 65, and 27.9 million pensions in payment. These payments overlap and are not mutually exclusive, unlike the case in Australia. However, the data clearly indicates that the coverage of the pension system in France is effectively close to 100%, emphasising that maintaining the generosity of pensions is in the direct interest of the majority of the French population.

This also extends to the working-age population.

This is an expanded version of an article published on The Conversation on 6 July 2023. Read Part 2 here.

Recent Comments