The redistributive effects of welfare states are usually assessed by considering their impact on the income distribution or the level of income poverty within a given year. However, changes in the income distribution also have long-term implications for the distribution of wealth, which accumulates throughout people’s life courses.

Generous social insurance systems, such as the one in France, require higher levels of contributory taxes, which in turn reduce the capacity of working-age households to save privately. The “tax wedge”, which encompasses income taxes, employer and employee social security contributions, and compulsory charges, amounts to 47% of total labour costs for average workers in France. In contrast, the tax wedge in Australia, including the Superannuation Guarantee, is 33%.

But high taxes pay for high benefits, and they also reduce the need for households to save, since they are promised a substantial proportion of their previous earnings when they retire (or become unemployed or sick).

As demonstrated by the calculations presented in the charts in Part 1, French households currently experience nearly the same levels of disposable income and living standards in retirement as they do during working years – so why wouldn’t they value retirement? And demonstrate against changes in the pension age.

In contrast, Australian households, with the exception of those with lower lifetime earnings, typically experience a much greater decrease in disposable income when they retire. Therefore, to avoid a substantial decline in living standards during retirement, Australians must save privately.

Australians face the need to supplement their age pension income, if applicable, and because they have been paying lower taxes during their working lives, they have a greater capacity to make these savings.

This means that the level of private wealth varies considerably across high-income countries. In Australia, the median private wealth level (on an exchange rate basis) is nearly twice as high as the level in France.

The structure of wealth holdings also differs, similar to the differences in overall wealth levels. In Australia, a larger proportion of wealth is tied to home ownership, partly due to the family home is not directly included in the pension assets test. Home ownership has been considered as an informal fourth pillar of Australian retirement incomes, but concerns about its long-term sustainability have emerged.

On the other hand, public pensions can also be viewed as a form of wealth, given that they represent promises of an income stream during retirement.

Public pension wealth is determined by the duration of pension benefit payments and the evolution of its value over time. Net pension wealth, which considers future discounted flows of pension benefits after taxes and social contributions, accounts for these factors. Pension wealth reflects the amount of money needed to buy a flow of pension payments equivalent to what is promised by the mandatory pension systems in each country. It is affected by life expectancy, the age at which individuals begin receiving their pensions, and the indexation rules that govern the adjustment of pension benefit payments.

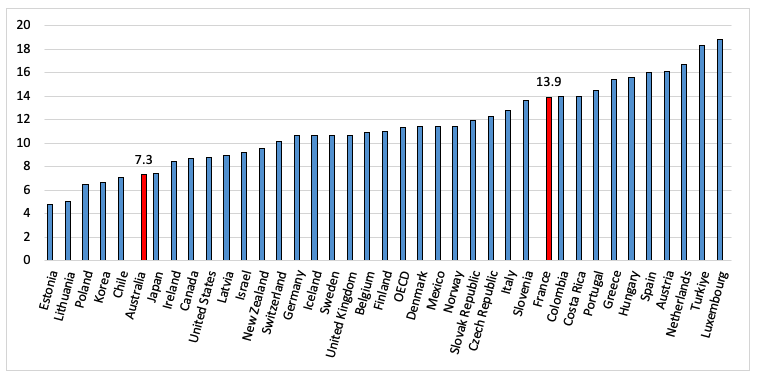

Chart 4: Net public pension wealth for men on average earnings, ratio to average male earnings, OECD countries, 2018

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance , 2021.

On this basis, Chart 4 shows that the net public pension wealth, including superannuation, of an Australian worker receiving the average wage is just over 7 years of average earnings. In comparison, the net public pension wealth for a comparable French worker is just under 14 years.

But because public pension wealth is strongly influenced by the duration of pension receipt, raising the pension age can be considered equivalent to reducing future wealth. Raising the pension age by two years corresponds to an approximate 8% reduction in future pension wealth for French workers in a single change.

And it applies to individuals who are still in the workforce, rather than those who have already retired. From this perspective, it is unsurprising that French workers protest.

Why was pension change easier in Australia?

Raising the pension age is often perceived as a more justifiable way of improving public finances and preparing for population ageing. This is because it both reduces the number of individuals receiving pension payments and potentially increases the number of people remaining in the workforce – a sort of “double whammy”.

Raising the pension age also does not result in a reduction of income for those currently receiving pensions, nor does it reduce the level of future pension income received each fortnight. However, as discussed above, it does reduce the overall level of public pension wealth. This may have a larger impact on people and groups who have a shorter life expectancy after retirement, as their accumulated wealth is more likely to be affected.

In particular, Indigenous men have a life expectancy that is nearly 9 years lower than non-Indigenous men, while for Indigenous women, the gap is close to 8 years. This disparity has led to a recent unsuccessful case before the Federal Court, advocating for a lower pension age for Indigenous Australians than for the non-Indigenous population.

However, it is important to recognise that in the Australian context, the increase in the pension age, which was legislated in 2009, was part of a broader program of reforms that included the largest single year increase in pensions in Australian history. This increase also applied to Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment.

Since the commencement of the increase in the pension age in 2017, there has been a notable rise in the number of individuals over 65 who receive Carer Payment, increasing from 42,000 to 61,000. Similarly, the number of recipients of Disability Support Pension has increased from 52,000 to 125,000 during the same period. But because the level of payments these groups receive is the same as the Age Pension, they are not disadvantaged by this change.

However, the number of individuals aged 65 years and over receiving JobSeeker Payment for the unemployed has increased from zero in June 2017 to 39,000 in March of this year, with further increases likely by 1 July. This group is severely disadvantaged by this change, as the level of payment for an older unemployed person is over $300 less per fortnight than the Age Pension, a gap that will only be slightly reduced by the increases announced in the most recent Commonwealth Budget.

Relatively little attention has been paid to this group despite their status as among the poorest in the Australian population. Due to the low level of payment they receive, these individuals have limited prospects for improving their financial circumstances.

In contrast, the government’s proposal to increase taxation on earnings in superannuation balances over $3 million starting in 2025 has drawn criticism, including from the Opposition.

The very different welfare states of Australia and France not unexpectedly have created different interest group coalitions, each with its own set of interests to protect.

This is an expanded version of an article published on The Conversation on 6 July 2023. Read Part 1 here.

It’s not wealth. It’s a mortgage over the earnings of other people’s children.