In last year’s Budget Forum, I forecast that excessive fiscal stimulus during COVID would lead to an outbreak of inflation and called for tighter fiscal policy to limit that outbreak. This year, I check on the accuracy of my inflation forecast and how fiscal policy has developed, and propose a new plan for personal income tax rates.

Inflation forecast

In last year’s Forum, I drew on my paper on Fiscal Policy in the COVID-19 era, now published in Economic Papers, to challenge the Budget forecast for inflation as follows.

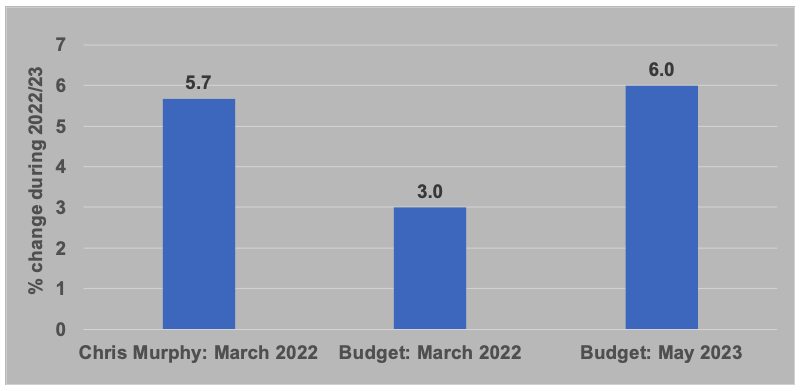

Pre-Budget, my paper forecast consumer price inflation of 5.75 per cent during 2022-23, compared to the Budget forecast of 3.0 per cent and the most recent Reserve Bank forecast of 2.75 per cent. I can’t recall such a striking difference in forecasts between the government and me in over thirty years of forecasting. In due course, it will become clear which inflation forecast is closer to the mark.

With the Consumer Price Index (CPI) now known for the first three quarters of 2022-23, it is clear my forecast was more accurate. Indeed, Treasury has increased its inflation forecast for 2022-23 from 3.0 per cent in last year’s Budget to 6.0 per cent in this year’s Budget, taking it close to my original forecast of 5.75 per cent (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Consumer price inflation forecasts for 2022-23

Source: Budget Papers

Of course, there is an element of luck in my inflation forecast being as accurate as it was, and Treasury’s forecasts are highly regarded. What is important is understanding the link between fiscal policy and inflation. My detailed economy-wide modelling predicted that ‘with most COVID restrictions on consumer spending now lifted, the excessive fiscal stimulus introduced in 2020 and 2021 will lead in 2022-23 to an upsurge in consumer spending triggering an outbreak of inflation’. I concluded that ‘less expansionary fiscal and monetary policy are needed now to limit this outbreak’.

Fortunately, monetary policy has responded. The cash rate has lifted from a highly expansionary 0.1 per cent to a mildly contractionary 3.85 per cent, just above an estimated neutral rate of 3 to 3.5 per cent. More tightening of monetary policy may be needed to bring inflation back to its 2 to 3 per cent target within a reasonable time frame.

Fiscal Policy

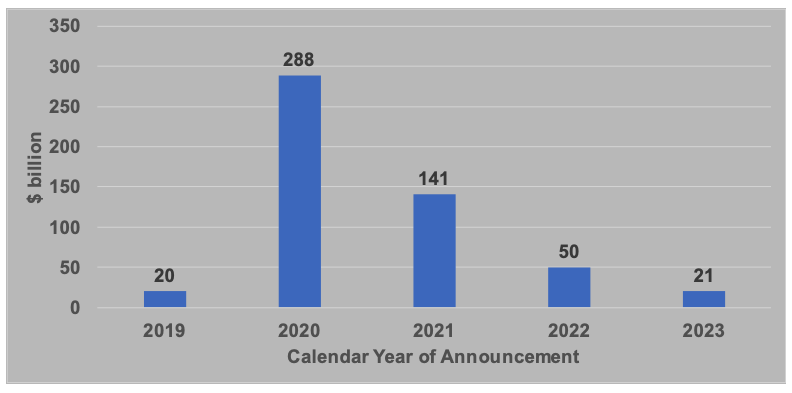

In contrast, while fiscal policy is now far less expansionary than it was during COVID, it is still expansionary rather than contractionary. Figure 2 shows the net cost to the Budget (over the forward estimates) of policy measures announced in each calendar year from 2019.

Figure 2: Net cost of policy measures over forward estimates

Source: Budget Papers

Figure 2 highlights the massive COVID fiscal stimulus of $429 billion during the COVID years of 2020 and 2021 combined. The main policy measures are set out in Table 5 of my paper. A large fiscal stimulus was warranted to dampen the economic downturn from COVID social distancing, but the size of the stimulus was overdone. My paper found that for every $1 of income the private sector lost under COVID, fiscal policy provided $2 of compensation, fueling subsequent inflation.

Similarly, research at the US Federal Reserve has found that Australia was one of 5 out of 17 OECD countries where fiscal policy over-compensated for COVID income losses, and that such over-compensation was systematically associated with substantially higher inflation outcomes post-COVID.

To help offset this over-compensation, in last year’s Budget Forum, and in a subsequent article in the Australia Financial Review, I called for fiscal tightening. Unfortunately, this has not happened.

In 2022, the former Coalition Government added a further $40 billion of net fiscal stimulus and the ALP Government $10 billion, giving a total of $50 billion (Figure 2). The latest Budget opened the account for 2023, adding a further $21 billion.

Hopefully, there are more savings measures to come in 2023, sufficient to switch from mild fiscal stimulus to mild fiscal tightening. Then, fiscal policy would be supporting monetary policy and so limiting the extent of further rises in interest rates. Further, an approach of implementing fiscal expansion when it is needed but not being prepared to implement tightening when it is needed, would only ratchet up government debt until it becomes unsustainably high.

Personal income tax rates

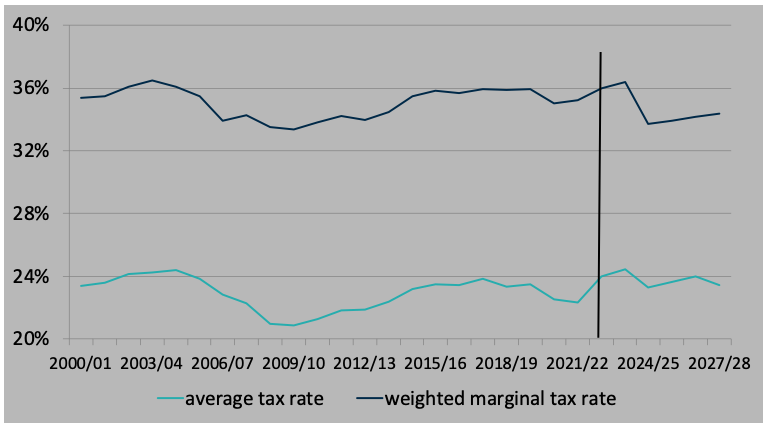

Under the 7-year personal income tax plan introduced in the 2018-19 and 2019-20 Budgets, tax ‘cuts’ are being implemented in three stages, although the ‘cuts’ go no further than returning the proceeds from bracket creep. Thus, by the time the plan ends in 2024-25, the average rate of tax is between 23 and 24 per cent, the same level as in 2017-18, the year before the plan started. Figure 3 shows how average and marginal tax rates evolve, on a weighted average basis, over the life of the plan and beyond.

Figure 3: Average and marginal rates of personal income tax

Note: Tax rates are weighted by taxable income.

While the plan does not change the overall tax burden, as measured by the average tax rate, it does reduce the weighted average marginal rate of tax, from 36 per cent to 34 per cent. This will be achieved by applying a reduced marginal rate of tax of 30 per cent, on annual income from $45,000 up to $200,000, under Stage 3 of the plan.

This lowering of marginal tax rates can be expected to improve incentives to work, save and live in Australia rather than elsewhere. But it also makes the tax-transfer system less redistributive. Some have suggested that Stage 3 be re-designed to reverse some reductions in marginal tax rates.

An alternative approach is to introduce a new plan that follows on from the old plan but returns the proceeds of further bracket creep differently. By 2027-28, there will be sufficient additional bracket creep to fund tax relief for low and middle income earners. To illustrate this, it is assumed in Figure 3 that the Low and Middle Tax Offset (LMITO) is re-introduced in 2027-28, but at a level that is 50 per cent higher than the old LMITO, that applied from 2018-19 to 2020-21 (and with adjustments to thresholds to allow for wage inflation in the intervening years). The new LMITO provides an annual tax cut of up to $1,620.

The proposed new plan returns the proceeds of bracket creep because it reduces the average tax rate back to between 23 and 24 per cent in 2027-28. Further, while the weighted average marginal rate of tax edges up under this plan, most of the reduction that occurred under the old plan remains intact, so there would be an ongoing improvement in incentives.

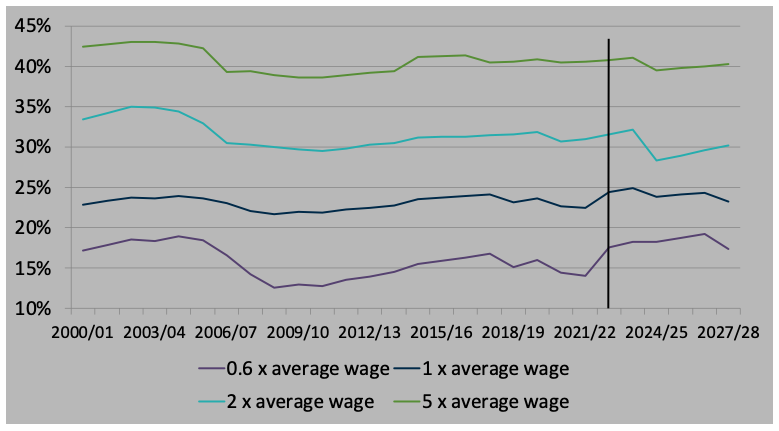

Figure 4 shows how these developments in tax policy would affect equity. The old tax plan particularly benefits upper middle income earners, with someone earning double average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE) for full-time adults receiving a noticeable reduction in their average tax rate from 2017-18 to 2024-25. In November 2022, AWOTE was $94,000 on an annual basis. By re-introducing an expanded LMITO, the new plan provides significant reductions in average tax rates for low and middle income earners in 2027-28. This includes those earning 60 per cent and 100 per cent of AWOTE (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average rates of personal income tax by wage

After five consecutive years of fiscal stimulus measures, the fiscal challenge ahead is to make budget savings not only for fiscal sustainability, but also to help the RBA in bearing down on high inflation. Following the Stage 3 personal income tax cuts, tax relief for low and middle income earners could be provided later using a new, expanded LMITO.

Other Budget Forum 2023 articles

The Costly and Unfair Stage 3 Tax Cuts Will Undermine the Progressive Income Tax and Worsen Inequality, by Kathryn James, Guyonne Kalb, Peter Mares, Miranda Stewart and Roger Wilkins.

Financial Support for Those on Low Incomes, by John Freebairn.

Will the Budget Reduce Inflation? By Michael Coelli.

Stage 3 Tax Cuts and JobSeeker – A Slightly Different View, by Andrew Podger.

Equity Is Hard to Achieve When Unfairness Is Baked into the System, by Robert Breunig.

A Small Investment in the Budget With a Big Policy Return? By Nicholas Biddle.

Labor Could and Should Have Gone Stronger on the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, by Rod Sims.

How Removing Parenting Payments When Children Turned 8 Harmed Rather Than Helped Single Mothers, by Kristen Sobeck.

Straightening Out the Super Tax Breaks Debate, by Brendan Coates and Joey Moloney.

The Priorities of Australians Ahead of Budget 2023-24, by Nicholas Biddle.

Recent Comments