Australia is one of the world’s richest countries but our government taxes and spends far less than most other OECD members. For decades, the richest 10 per cent of Australians have been capturing a growing share of income, while the poorest 10 per cent remain trapped in poverty. The Stage 3 tax cuts will widen this divide and entrench the structural budget deficit. It is disappointing that the recent federal budget retained this bad policy that runs counter to Australia as the land of the fair go. However, the response to the budget shows that this is an issue which will not go away. We argue that the debate on the Stage 3 tax cuts should be the beginning of a broader discussion about the fairness and progressivity of the income tax in our overall tax and transfer system.

Flattening and compressing of the progressive rate structure

In the 20th Century, Australia was one of a select group of rich nations to develop a progressive income tax system. In 1950 we had 28 tax brackets, with a top marginal rate of 75 per cent. That kicked in when annual income ticked over 10,000 pounds, which was about 33 times the average wage of a male factory worker.

Today there are 5 brackets with a top rate of 47 per cent (including the Medicare levy) for incomes above $180,000 (roughly double average male full-time earnings).

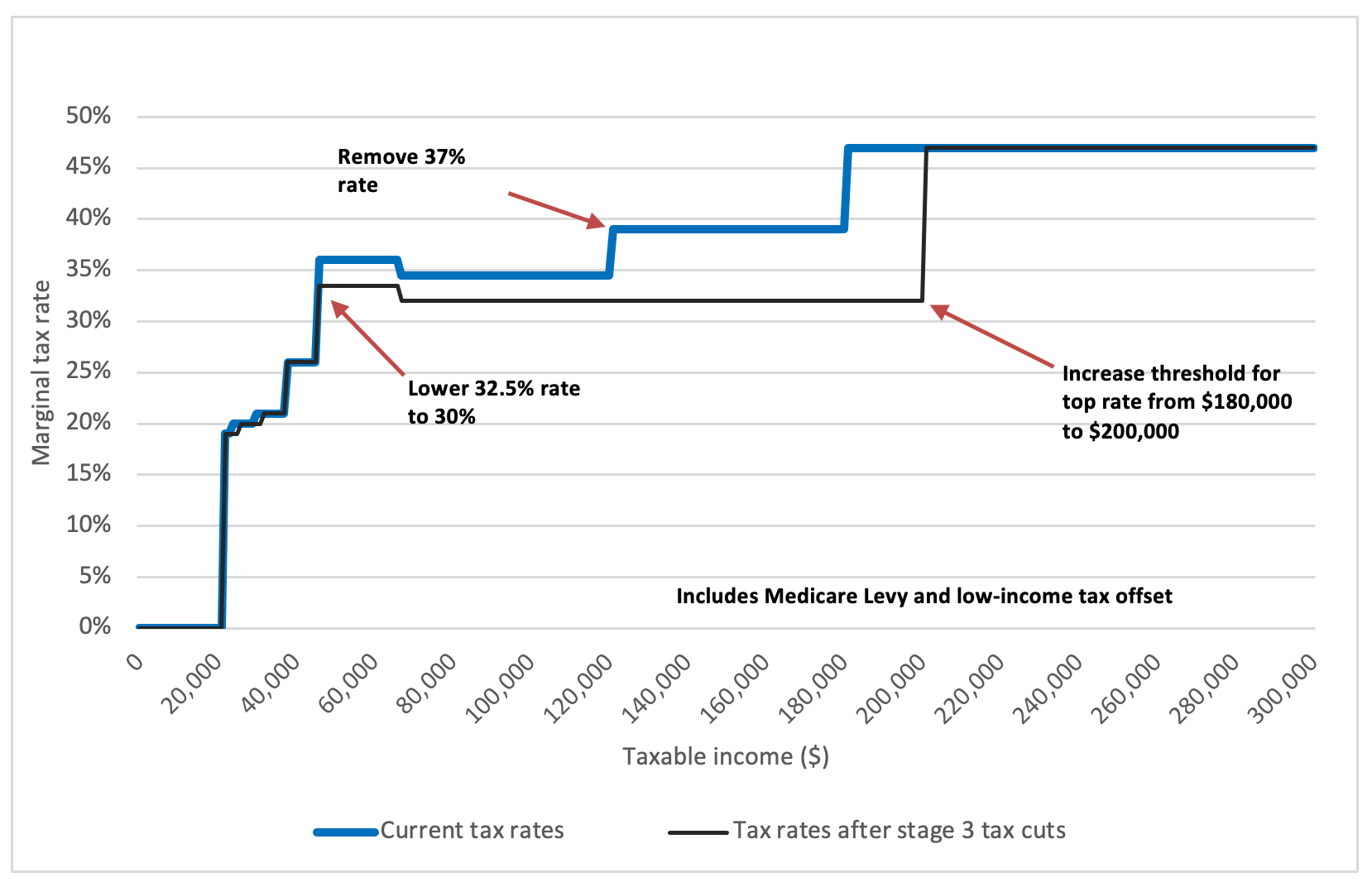

The Stage 3 tax cuts will further flatten and compress the progressive rate structure by increasing the threshold for the top rate from $180,000 to $200,000. It will completely remove the 37 per cent tax bracket and lower the next tax rate from 32.5 per cent to 30 per cent. This will then be the rate that applies to all income between $45,000 and $200,000 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: What is the Stage 3 Tax Cut?

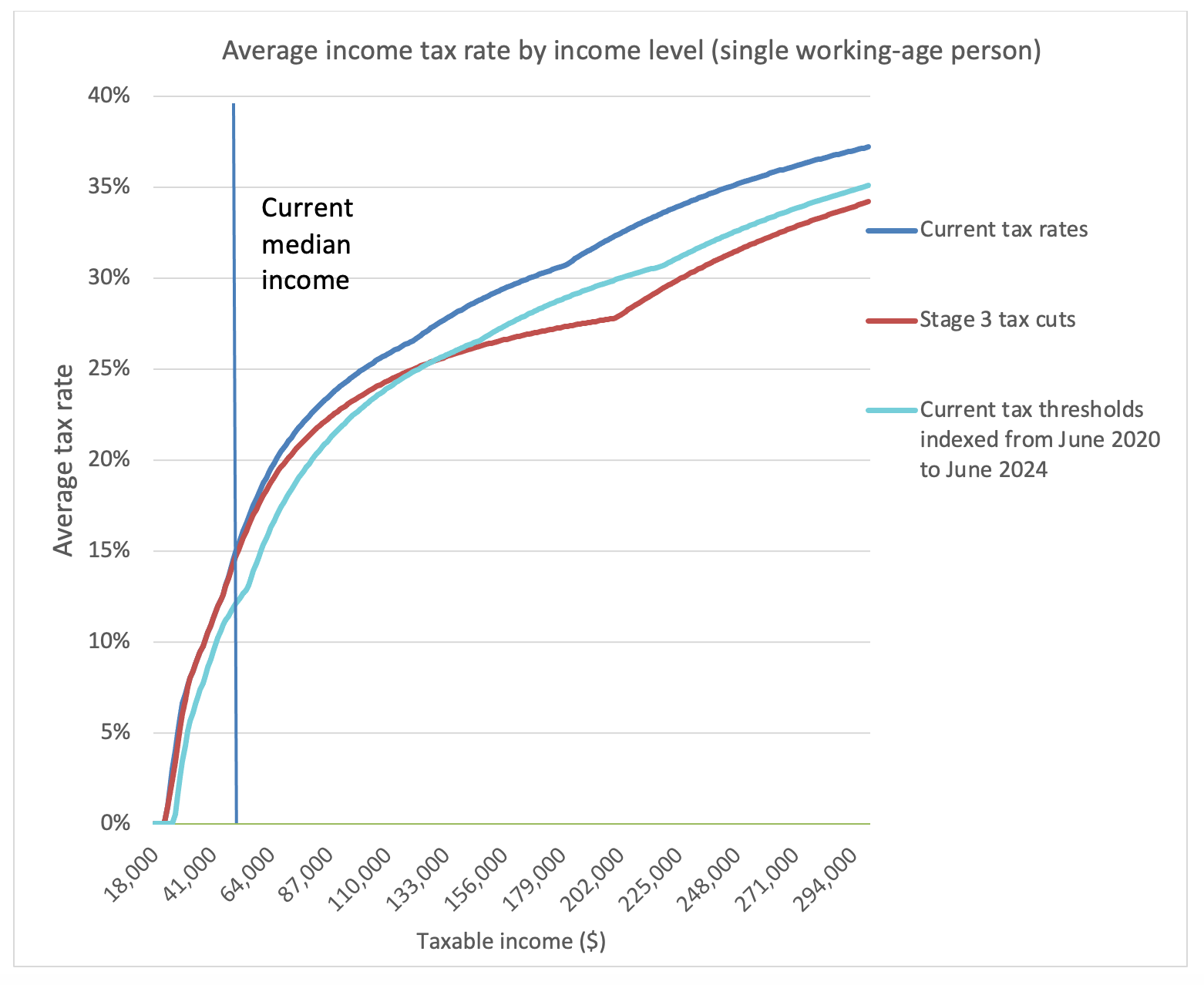

These tax cuts significantly reduce revenue and shift the burden of taxation away from top-income earners and towards low- and middle-income taxpayers. They overcompensate high-income earners for bracket creep (the rise in the share of income paid in taxes due to inflation) while doing little or nothing to address the issue for Australians on lower incomes who will pay more tax after the removal of the low and middle income tax offset (LMITO) from July 1 this year (see Figure 2; the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods also made similar findings).

Figure 2: Distributional effects of Stage 3 tax cuts versus adjusting for inflation

Less revenue means less can be done for low-income households struggling with the cost of living

The most recent estimate of the cost of the Stage 3 tax cuts by the Parliamentary Budget office estimates a cost of $20.4 billion in 2024-25 and a total cost over a decade of $313 billion. That means less money to spend on alleviating poverty to improve fairness and social and economic outcomes overall.

For example, the estimated $69.1 billion in revenue foregone over the forward estimates from 2024 to 2027 could more than fund the combined cost of the $34 billion needed to increase in Jobseeker and rent assistance to a liveable rate over the same period; the Commonwealth Government’s $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund; and the $1.1 billion needed to restore the single parent payment to continue until the age of 16 for the youngest child over the next three years.

The fiscal cost of the Stage 3 tax cuts keeps rising because taxes are estimated in nominal dollars. This nominal approach is the standard approach to policy costing for all tax and expenditure measures in the budget. Some have suggested that the 10 year fiscal cost of the tax cuts is a mirage, implying that tax rate reductions (for example, to return some bracket creep) would certainly be made in their absence. But the level of any tax cut, raising thresholds or returning bracket creep is a policy choice that demands an honest political debate.

The distributional effects are made worse by Australia’s narrow income tax base

A progressive income tax is achieved not just by the rate structure but also by the base – that is by what income we choose to tax. When Australia’s income tax was enacted more than a century ago, we taxed income from capital at a higher rate than income from work. That differential was removed, but in the 1980s, Australia introduced a capital gains tax and other reforms to significantly broaden the income tax base.

Since then, tax concessions have crept back into the law in favour of capital income. These include the overly generous capital gains discount, excessive concessions for superannuation and negative gearing. As higher-income earners can save much more than low-income earners, this narrowing of the tax base reduces revenue and makes the tax system less fair.

As the commitment to a progressive income tax rate and broad base has declined, inequality has risen, pushing the tax burden onto the middle and benefiting the rich. Top-income earners pay a large share of tax in our system because they have more capacity to pay, but the many avenues available to well-heeled taxpayers to shelter wealth and income mean it is unlikely they pay anything close to the statutory tax rates on their actual income.

It is often argued that tax rate cuts and concessions foster economic growth. But today’s economic research suggests that taxing capital adequately is both equitable and efficient and highlights the economic damage done by growing inequality and poverty. This argument also ignores the growth and social benefits delivered to Australians by increased spending on public goods such as health, housing and education.

How to fix it?

The Stage 3 tax cuts should not go ahead as currently designed. The government should, at least, return the 37% tax rate at a suitable threshold, which the Grattan Institute estimates would save $8 billion a year. Australia needs a broader discussion about restoring the progressive rate structure and base of the income tax to capture more tax from capital and wealth. This would ensure people pay a fair amount of tax, based on their ability to pay while raising the revenue the government needs to provide the services and infrastructure Australians expect and need.

This is an updated version of our piece published on Crikey on 8 May 2023.

Other Budget Forum 2023 articles

Inflation Forecast, Fiscal Policy and Personal Income Tax Rates, by Chris Murphy.

Financial Support for Those on Low Incomes, by John Freebairn.

Will the Budget Reduce Inflation? By Michael Coelli.

Stage 3 Tax Cuts and JobSeeker – A Slightly Different View, by Andrew Podger.

Equity Is Hard to Achieve When Unfairness Is Baked into the System, by Robert Breunig.

A Small Investment in the Budget With a Big Policy Return? By Nicholas Biddle.

Labor Could and Should Have Gone Stronger on the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, by Rod Sims.

How Removing Parenting Payments When Children Turned 8 Harmed Rather Than Helped Single Mothers, by Kristen Sobeck.

Straightening Out the Super Tax Breaks Debate, by Brendan Coates and Joey Moloney.

The Priorities of Australians Ahead of Budget 2023-24, by Nicholas Biddle.

If one is concerned about inequality (especially intergenerational inequality – which I am) in terms of opportunity (as opposed to outcome) why not just abolish income tax altogether and levy a 5% plus land value rent charge on the unimproved value of all land and natural resources, including mining tenements and spectrum? You would flush out a lot of illegal disguised foreign ownership and proceeds of crime to boot.

PS In the 1950s we had exchange controls and did not sign tax treaties with low rates for certain passive classes of investment income. Do you want Australian owners of taxed capital income bought out by foreign pension funds etc – as is happening with our infrastructure?

Income Tax should encourage physical workers to work and not get taxed heavily. Office workers can afford to pay heavy taxes. Just ask the tradies on Construction industry and oil riggers doing demanding heavy work if they would work “Extra ” if taxed heavily. Look at the U.S.A tax system under $500,000 tax brackets. My suggestion is as follows: No medicare Levy to apply.

$45,000 – $225,000 @ 30%

$225,000 – $300,000 @ 40%

$300,000- $450,000 @ 50%

$450,000 and over at 55%

Death Tax Exemption of $20 million and 25% over

on all assets. Sales tax increased and GST increased to 12.5% with 2.5% going to the Federal Gov’t.

Company Tax of 35% and Minimum Tax of 0.7% on all company Receipts like in Texas USA so that all companies pay a minimum amount of tax. We must look at other revenue sources and not tax hardworking people.

By the way, if you are going to look at tax scales in the 1950s, and try to use them to make comparisons, please do remember there was no capital gains tax then and the High Court had not done a Myer Emporium exercise.

There is indeed a very good argument for not taxing capital gains as they are not income – contra Henry Simons et al.

The Smithian British tradition is correct. Capital gains are the increase in value of an income producing asset. If that income is taxable the capital gain reflects the capitalisation of the after tax income stream, so CGT becomes double taxation.

At a more fundamental level, where do capital gains arise? Plant and machinery depreciate – no capital gains there. Shares represent claims to the assets of businesses. Those assets are land, plant etc and goodwill. Goodwill is merely the value of an expected taxable income stream.so back to the double tax problem.

If you strip it down, the only really appreciating asset is land so why not save yourself the trouble and charge it directly with a land value rate? You might actually clean out a lot of illegal disguised foreign “investment” and dirty money – and make a profit in doing so which will enable you to cut taxes on labour..

Pingback: Labor had no choice on stage 3 tax cuts

Pingback: Labor had no choice on stage 3 tax cuts - independent news and commentary Australia