As previously noted, since 2013 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has embarked on a transformation project, aiming to transform how it goes about its core business, and make it a contemporary and service-oriented organisation. A major driver of the ATO’s transformation was acknowledgement of the growing community expectations around government services being simpler, faster and easier to use.

Recognising the change in community expectations, the Australian Government developed the digital transformation agenda led by the Digital Transformation Office (DTO). In the 2015-16 Federal Budget, the Government announced its intention to proceed with the ‘reducing red tape – reform to the Australian Taxation Office’ measure. Part of this measure included the Digital by default initiative, ‘a proposal that will progressively make the method of interacting with the ATO, in a digital manner, with support for those unable to transition.’ This initiative means that the ATO will require most people to use their digital services to send and receive information and payments to and from the ATO.

Thus, with digital solutions proposed as the primary medium of service delivery, the way in which information is provided to taxpayers, the ATO’s interactions with taxpayers and their inbound and outbound transactions will undergo significant transformation in all areas of the ATO’s tax administration, including tax dispute resolution.

Dispute systems design approach

The purpose of this article is two-fold. First, this article seeks to provide a brief summary of a dispute systems design (DSD) evaluation of the Australian tax dispute resolution system in the context of the various digital initiatives introduced as part of the ATO’s Digital by default initiative. Secondly, based on the DSD evaluation conducted, this article aims to provide some recommendations on the Australian tax dispute resolution system for the ATO going forward.

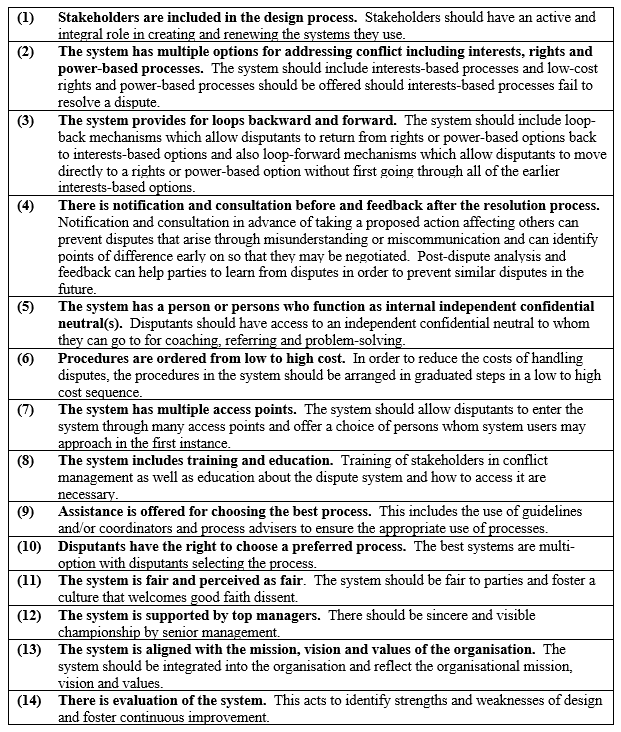

DSD refers to a deliberate effort to identify and improve the way an organisation addresses conflict by decisively and strategically arranging its dispute resolution processes. A number of DSD principles of best practice have been developed by various DSD practitioners over time. Following the prior evaluation of the Australian system, this evaluation was conducted using the 14 DSD principles of best practice outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: The 14 Dispute Systems Design Principles Used in this Study

Findings and Recommendations

As noted above, similar to many tax authorities around the world, the ATO is now, more than ever, focussed on using digital solutions to improve client experiences, to make it easier for taxpayers to meet their obligations, to streamline processes, and to better tailor and target their services and enforcement.

The main findings from the DSD evaluation of the Australian tax dispute resolution system in the context of the ATO’s digital transformation agenda are summarised below:

- The ATO includes stakeholders in the design process and engages with the community to co-design products and services, including through the ATO’s Let’s Talk website which provides an online chat, consultation and feedback forum (DSD Principle 1).

- With respect to notification before the resolution process (DSD Principle 4), the ATO has published income tax risk reports to let taxpayers know what behaviours, characteristics and tax issues attract the ATO’s attention and thus, identify areas where disputes potentially may arise. In addition, drawing from behavioural economics research to encourage ‘good behaviour’, the ATO has been using automated SMSs (rather than formal letters) to notify habitual late lodgers and payers.

- The ATO’s digital transformation adds to the provision of multiple access points to the dispute resolution system (DSD Principle 7) through the introduction of an , online and screen share services and , who is the ATO’s virtual assistant that understands conversational language and is always available on ato.gov.au to help with general tax enquiries.

- In relation to the education of stakeholders (DSD Principle 8), the ATO has transformed its website to ‘deliver a better online experience.’ From 1 March 2015, the ATO website went through a site-wide refresh, including reducing the number of words on ato.gov.au by approximately 5.3 million words (45 per cent), removing duplication and complexity to allow greater ease of use for users in obtaining information. The ATO has also created a digital application (the ATO app), which can be downloaded onto a smart phone or tablet and features a range of tools and calculators for taxpayers.

- The digital transformation of the ATO has enhanced the ability for disputants to choose a preferred process in the dispute resolution system (DSD Principle 10) through the introduction of, as noted under DSD Principle 7 above, online and screen share services, , the ATO’s virtual assistant, and an service for more specific support. These digital options are available to be utilised by taxpayers alongside the formal disputes process.

- As stated under DSD Principle 1 above, the ATO’s digital transformation includes the ATO’s engagement with the community in the co-designing of products and services and to get feedback on the ATO’s performance. Thus, evaluation of the digital aspects of the dispute resolution system occurs through its analysis of feedback collected from community satisfaction and staff engagement surveys, and feedback from ATO testing grounds such as its Beta site for website and online product development (DSD Principle 14).

Research on vulnerable taxpayer groups

The digital solutions introduced as part of the ATO’s Digital by default initiative, including as outlined above, online web chat and screen share services, virtual assistance, a digital app and SMS notifications, provide a number of benefits to those taxpayers who have internet access and those who have the requisite skills and knowledge to navigate digital channels. Implicitly, taxpayers with access to the system, and who have the knowledge and skills required to use it, will be more informed and will be able to interact with the ATO in a more convenient way.

However, due to the existence of a digital divide, these benefits may not necessarily accrue to vulnerable taxpayer groups (namely, low income earners, the elderly, the disabled and taxpayers with limited English proficiency) who may not have access to digital channels and/or who may be unable or unwilling to use them.

To date, there has been no specific research conducted by the ATO on understanding the potential implications of the increasing digitisation of service provision and information dissemination on vulnerable taxpayer groups with no or low access to digital channels. Furthermore, statistics on the use and extent of the benefits of digital solutions with respect to the resolution of tax disputes for different types of taxpayers are unknown.

Accordingly, research on the particular needs and preferences of vulnerable taxpayer groups is required by the ATO in order to further design online services in a manner most likely to address the barriers faced by vulnerable taxpayers and provide alternative options for those who are unable to interact digitally, as well as enable the effectiveness of the digital solutions employed to date to be evaluated across taxpayer groups.

While research on vulnerable taxpayer groups’ service needs and preferences is applicable to all areas of tax administration where the ATO interact with taxpayers, it is of particular significance to tax dispute resolution in order to improve equity of access issues associated with tax dispute resolution as well as enhance perceptions of fairness of the dispute resolution system (DSD Principle 11), and consequently, improve voluntary taxpayer compliance.

This article is based on: Jone, Melinda ‘A Preliminary Evaluation of Australia’s Tax Dispute Resolution System in the Context of the ATO’s Reinvention Program’ (2019) 34(3) Australian Tax Forum.

Recent Comments