Since 2013 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has embarked on a transformation project, Reinventing the ATO, in which it aims to transform how it goes about its core business, and make it a contemporary and service-oriented organisation. Managing and resolving tax disputes in a way that is efficient, respectful and fair, including through using alternative dispute resolution (ADR), has formed part of the project. Set against the background of the reinvention project, this article outlines certain dispute systems design (DSD) principles of best practice displayed by the Australian tax dispute resolution system.

DSD began in the context of workplace disputes and can be traced to the publication of Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems to Cut the Cost of Conflict by Ury, Brett and Goldberg in 1988. Their research drew on empirical evidence in the particular context of disputes in an unionised coal industry. DSD has since been applied in other dispute resolution contexts, including in tax dispute resolution.

DSD refers to a deliberate effort to identify and improve the way an organisation addresses conflict by decisively and strategically arranging its dispute resolution processes. It includes a focus on the use of interests-based processes (such as negotiation and mediation) as the primary mechanisms of dispute resolution. DSD aims to reduce the cost of handling disputes and produce more satisfying and durable resolutions. A significant volume of research shows that interests-based approaches produce more cost-effective, satisfying long-term and sustainable solutions to disputes, particularly when those disputes occur within the context of a continuing relationship. The use of ADR to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of tax administration as well as to provide flow-on improvements to taxpayer compliance by making it easier to resolve disputes with revenue authorities, or even to allay taxpayer concerns, is consistent with the aim of DSD.

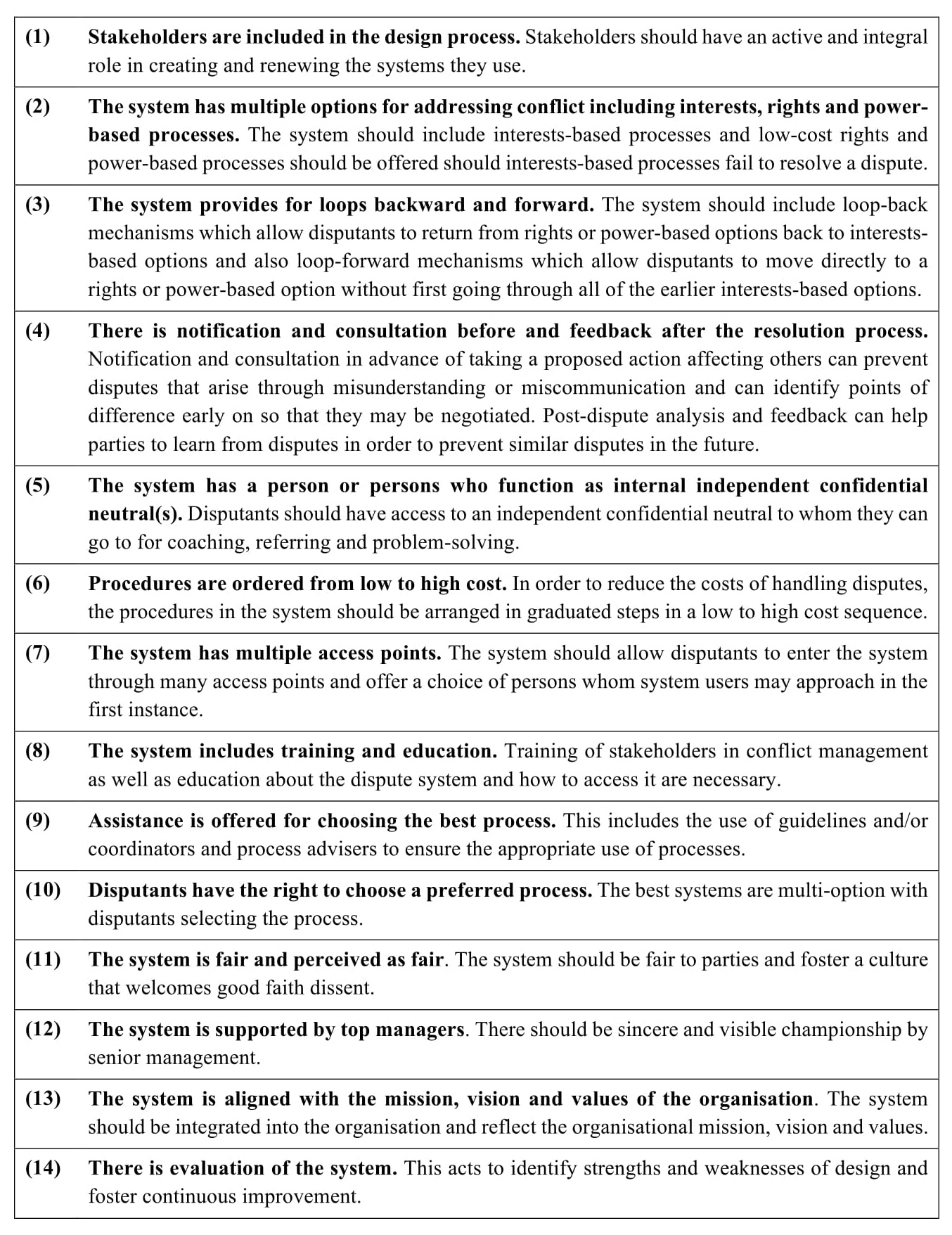

A number of DSD principles of best practice have been developed by various DSD practitioners over time. These principles are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Dispute Systems Design Principles

It is beyond the scope of this article to undertake a comprehensive evaluation (encompassing both the design strengths and weaknesses) of the Australian tax dispute resolution system, using DSD principles. However, outlined below are some of the key design strengths displayed by the Australian tax dispute resolution system, set in the context of the ATO’s reinvention program. Championing a dispute resolution culture, and ADR, are recurrent themes in the speeches of senior ATO members, including the Australian Commissioner, Second Commissioner, Law Design and Practice and the Deputy Commissioner, Review and Dispute Resolution (RDR). This practice of the ATO aligns with the DSD literature which provides that:

At least one senior person must be a visionary who champions the cause of creating a conflict-competent culture … The champion’s passion inspires others to act. It is this ability to connect others to a vision that often drives the success of a program.

As noted earlier, since his appointment in 2013, the current Australian Commissioner has embarked on a project of Reinventing the ATO. The reinvention project has three main streams – transforming the client experience, transforming the staff experience and changing the ATO culture. It follows that the tax dispute resolution system (and ADR) are integrated within the wider tax administration system by managing disputes fairly and effectively – this is an important part of the reinvention program. To give effect to this, a number of processes have been implemented by the ATO to resolve disputes as early as possible. These processes include: encouraging early engagement with taxpayers at both the audit and objection stages; the introduction of an independent review process for large business taxpayers; and the increased use of ADR, including the introduction of in-house facilitation. The ATO has indicated a continuing commitment towards incorporating dispute resolution, including ADR, within the organisation. “Resolving disputes” was first included as a dedicated focus area of the ATO Corporate Plan 2014-18 and there has been further inclusion of the topic in subsequent ATO corporate plans. The ATO’s annual reports also include a separate section reporting on “resolving disputes”.

In addition, as part of the transformation of the organisation, various ATO staff have undergone training on how to better communicate with taxpayers during disputes. The ATO has also established a Case and Technical Leadership group within RDR to provide mentoring and leadership to RDR staff in objections, ADR and litigation. With respect to in-house facilitation, various frontline ATO staff have undergone training/awareness sessions on the benefits of in-house facilitation as a suitable approach to resolve less complex disputes. Externally, the ATO has worked to raise awareness of its in-house facilitation service through interaction and consultation with professional associations and the legal profession. For example, the RDR group has had various interactions with the Dispute Resolution Working Group and the Legal Practitioner Roundtable.

In relation to the evaluation of the system and the reporting of feedback on tax disputes, the ATO has had its ADR processes independently evaluated to help build community confidence in the use of ADR in tax disputes. The ATO engaged the Australian Centre for Justice Innovation (ACJI) at Monash University to conduct a feedback survey involving all participants in ADR processes with the ATO. The findings were outlined in a final report made publicly available on the ACJI website. The survey findings provided insight into the quality and effectiveness of the ATO’s use of ADR and identified areas for improvement. The ATO also conducts (and publishes) quarterly surveys on taxpayers’ perceptions of fairness in disputes. The ATO’s organisational strategies to improve taxpayer perceptions of fairness, in line with their reinvention program, draw on insights gained from this research.

Other countries could draw from certain design strengths of the Australian system, set in the context of the ATO’s reinvention project, with respect to: stakeholder involvement in the design process (DSD Principle 1); the provision of feedback on disputes (DSD Principle 4); inclusion of education and training (DSD Principle 8); support and championship of the system by senior revenue authority members (DSD Principle 12), alignment of the dispute resolution system (and ADR) with the wider tax administration system (DSD Principle 13); and evaluation of the system (DSD Principle 14).

This article has focused on selected examples of the design strengths of the Australian system which arguably can be viewed as primarily being associated with the more cultural aspects of design (as opposed to structural design aspects). However, these aspects of DSD best practice are of potential significance to other jurisdictions seeking to develop or improve their tax dispute resolution systems, particularly in the light of the various transformation or modernisation programs currently being undertaken by various tax administrations around the world. Moreover, these aspects of DSD are important given that the way in which tax disputes are managed and resolved can have a significant impact on the overall experience that taxpayers may have in interacting with revenue authorities, which in turn can impact on taxpayer voluntary compliance.

This article is based on: Jone, Melinda, ‘What can the United Kingdom’s tax dispute resolution system learn from Australia? An evaluation and recommendations from a dispute systems design perspective’ 2016 32(1) Australian Tax Forum 59-94. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2954289

Recent Comments