Despite some analysis from the media suggesting single parents might find being on welfare more attractive than working, more than half of sole parents in Australia are in work and are better off as a result.

Australia’s tax and social security systems are designed to collect revenue on a fair basis, to provide a means tested safety net to protect people from poverty, to support the cost of raising children and to encourage work.

The Treasurer recently said that the, “ultimate test for any welfare system and any tax system [is that they are] well synchronised.” As the Treasurer went on to say, this means that “if you are of working age in this country and you are able to work that you are better off in work than you are on welfare.”

There has been recent public debate about whether Australia’s tax and social security systems do meet the goal of ensuring that welfare recipients have a financial incentive to seek work and, if they are working part time, to work more hours.

Does welfare for sole parents pay more than work?

We looked in detail at the case of a sole parent with four kids aged 13, 10, 7 and 4, proposed by Sarah Martin, “Parental Welfare Pays More than Work” in the Australian, 28 October 2016. Martin said that, “thousands of parents claiming government benefits are financially better off not getting a job,” and that 10% of parenting payment recipients, or about 43,200 people, were better off than a median wage earner. However, this view fails to take account of benefits paid in work, designed to ‘make work pay.’ It also overlooks the relative needs of such a family.

Further, as the Australian Council of Social Service observed, four kids and a single parent is a pretty unusual family structure these days.

Sole Parent Example: Jane

Let’s call our sole parent Jane, as more than 85% of sole parents are mothers. If Jane is not in the paid workforce, she would take home $52,469 in government benefits for the year to raise her family. We show later that this is close to the ‘Henderson poverty line’ for this family type. The Henderson poverty line benchmarks the basic income required to support different family units, and was originally set out in the 1973 Henderson Commission of Inquiry into Poverty.

Jane does not face a simple choice between welfare and work. Our system is designed to encourage work, so Jane will continue to receive family benefits in work. When Jane’s youngest child turns six, Jane is required by law to seek work (or study) for at least 15 hours a week, to get the benefits.

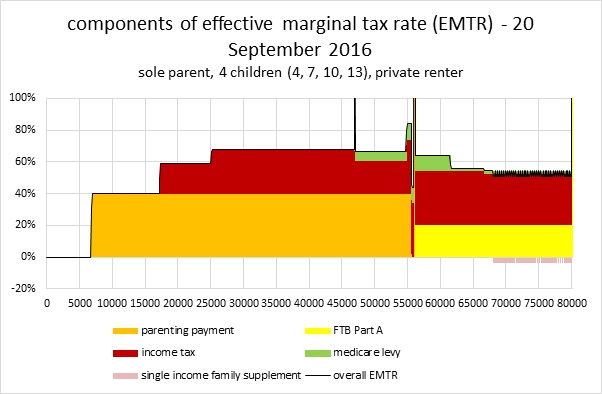

Financial incentives to work are produced by the net take-home income of a family, after tax paid and benefits received. This is reflected in the ‘Effective Marginal Tax Rate’ (EMTR), which takes into account tax paid and benefits lost as income from work rises; and the participation tax rate, which is the average EMTR over a range of income given the decision to take up work. The EMTR for Jane for earnings up to $80,000 is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 EMTR for Jane: sole parent with 4 children

Jane can earn just over $6,000 with no tax or loss of benefits. The EMTR on her next $10,000 is 40% and then to the median wage of $61,300, it is 60%-65%.

Up to the median wage, Jane’s participation tax rate is about 55%, so she is financially better off by at least $45 for each $100 earned after benefits phase out and tax is paid. It’s clear that working pays for Jane, even though the EMTR looks quite high. The “spikes” where the EMTR reaches 100% apply over a small range; hence they do not affect the overall picture. The coloured areas show the income tax on Jane (red), Medicare Levy (green) and withdrawal of parenting payment and Family Tax Benefit A (yellow) as her wage income rises.

More detail about EMTRs and how they are produced by the interaction of tax and transfer systems is in Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Policy Brief 1/2016 by Ingles and Plunkett. It also includes discussion of possible policy responses to improve work incentives.

Jane’s net take home pay for each extra day she works

We can show Jane’s net position after tax and benefits, for each extra day she works, from one day up to five days (full-time). To do this, we need to assume a wage rate for Jane.

Assuming the median wage of $61,300 (full time, men and women), Jane’s hourly wage rate is approximately $37. The “part time inclusive” median wage of $46,200 adopted by Sarah Martin in the Australian confuses the hourly wage rate and the hours worked. However we do use this lower wage later.

We also assume, like Martin, a rental housing cost for Jane of $20,800 or $400 per week, at the low end for Sydney. Even at this modest rent, Jane would be in “housing stress,” paying more than 30% of her income in rent.

Jane’s net position if she goes to work for one day up to five days is shown below (ignoring childcare and other costs). It shows a total gain from working of $27,150 a year if Jane works full-time.

Table 1 reward for working, sole parent, Median F/T wage rate $37/hr, days worked 0-5

| Annual Equivalent | ||||||

| Earnings | 0 | 12260 | 24520 | 36780 | 49040 | 61300 |

| Income support | 19674 | 17499 | 12595 | 7691 | 2787 | 0 |

| PES | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FTB A | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 26434 |

| FTB B | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 |

| Tax | 0 | 0 | -1374 | -4741 | -8007 | -11389 |

| Medicare | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -213 | -1208 |

| Disposable income (pre-costs) | 52469 | 62554 | 68536 | 72525 | 76402 | 79619 |

| Concession Card Type | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | None |

| Accommodation | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 |

| Disposable income after costs | 31669 | 41754 | 47736 | 51725 | 55602 | 58819 |

Source: D Plunkett model

Work pays for Jane even if she only works one day a week. However, Jane does less well from days three to five of work, due to the relatively high EMTRs which apply over the income range of $30,000 to $60,000.

The poverty line for a sole parent with four kids

The implication of the debate about being “better off” on benefits is that welfare is too generous. But this needs to be put into perspective.

For Jane’s family with four children aged 4 to 13, the standard Australian Henderson poverty line in June 2016 was $52,191 (not working) and $57,373 (working). That means the parenting benefits that Jane receives keep her family just at the poverty line. Working, as you might hope, actually raises Jane’s family out of poverty.

By contrast, the poverty line for a single person not in work was $22,211 and in work, $27,392. So even after paying income tax, a single person on a median income would be comfortably out of poverty.

Costs of Childcare

Both the Treasurer and the Australian article noted above are silent on the issue of childcare. This is strange because, unless Jane has a relative who can provide care for free, childcare for her four year old and after-school care for her seven year old and 10 year old are crucial for her to work.

Childcare is supported by a childcare rebate and childcare benefit, which are currently proposed to be consolidated into one payment in the Government’s childcare reform package introducing Child Care Subsidy from the Budget. This new package is important, but Ministers Christian Porter MP and Simon Birmingham MP insist they will not “add” childcare to “the nation’s credit card,” but must fund it by trading off with other social security cuts. This trade-off includes family benefits, as explained here, which will make many families worse off.

Modelling childcare is complex because of the diverse hours, packages and fees for care. We have done a simple model of Jane’s situation with childcare added (under the current regime). We’ve assumed Jane’s middle two children are in after-school care for 3 hours for each day she works, and the youngest is in long day care (LDC), charged for 10 hours for each day worked (session basis). We used $10 per hour for LDC and $6 per hour per child for after-school care. Finally, we assume she had no childcare for the eldest child.

Table 2: Reward for working after childcare costs, sole parent Median F/T wage rate $37/hr, days worked 0-5

| Annual Equivalent | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ |

| Earnings | 0 | 12260 | 24520 | 36780 | 49040 | 61300 |

| Parenting Payment (Income support) | 19674 | 17499 | 12595 | 7691 | 2787 | 0 |

| Family Tax Benefit A | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 26434 |

| Family Tax Benefit B | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 |

| Income Tax | 0 | 0 | -1374 | -4741 | -8007 | -11389 |

| Medicare Levy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -213 | -1208 |

| Child Care Benefit | 0 | 3858 | 7716 | 11576 | 14475 | 16822 |

| Child Care Rebate | 0 | 1607 | 3214 | 4820 | 6906 | 9269 |

| Disposable income (pre-costs) | 52469 | 68020 | 79466 | 88921 | 97784 | 105710 |

| Concession Card Type | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | None |

| Accommodation | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 |

| Child Care | 0 | 7072 | 14144 | 21216 | 28288 | 35360 |

| Disposable income after costs | 31669 | 40148 | 44522 | 46905 | 48696 | 49550 |

Source: D Plunkett model

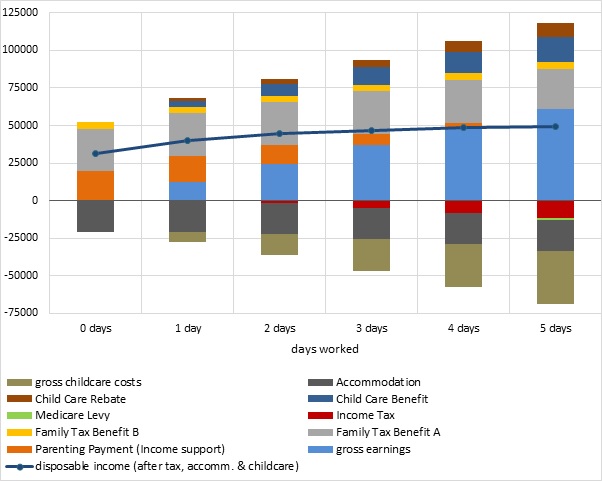

These tables can be represented graphically. The upper portion of the bars in Figure 2 represent the components of gross income; the lower portion the components of gross costs (rent, childcare and tax). The resultant is the disposable income line shown in blue. It can be seen that this is relatively flattened, particularly after days 1 and 2.

Figure 2 Reward for working after childcare costs, sole parent Median F/T wage rate $37/hr, days worked 0-5

Source D Plunkett model

Reward for working – average sole parent hourly rate

Median full-time income used in the previous graphs includes both males and females. Females, especially sole parents, may realistically have lower incomes than this. So we now use an hourly rate ($30) derived from median full and part time earnings of $46,500 pa. These figures are consistent with those used in the Australian article cited. They are also consistent with the average wage for a sole parent as calculated by the ABS. For single parents who are employed their mean hourly rate is $29.30 and median is $26.25 per hour. These figures are based on the ABS Survey of Income and Housing updated to 2016.

Table 3: Reward for working after childcare costs, sole parent wage rate $30/hr, days worked 0-5

| Annual Equivalent | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | $ |

| Earnings | 0 | 9300 | 18600 | 27900 | 37200 | 46500 |

| Parenting Payment (Income support) | 19674 | 18683 | 14963 | 11243 | 7523 | 3803 |

| Family Tax Benefit A | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 | 28313 |

| Family Tax Benefit B | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 | 4482 |

| Income Tax | 0 | 0 | -255 | -2264 | -4858 | -7453 |

| Medicare Levy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Child Care Benefit | 0 | 3858 | 7716 | 10353 | 13253 | 14475 |

| Child Care Rebate | 0 | 1607 | 3214 | 4496 | 6581 | 6906 |

| Disposable income (pre-costs) | 52469 | 66244 | 77033 | 84523 | 92495 | 97027 |

| Concession Card Type | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC | PCC |

| Accommodation | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 | 20800 |

| Child Care | 0 | 7072 | 14144 | 19344 | 26416 | 28288 |

| Disposable income after costs | 31669 | 38372 | 42089 | 44379 | 45279 | 47939 |

Source: D Plunkett model

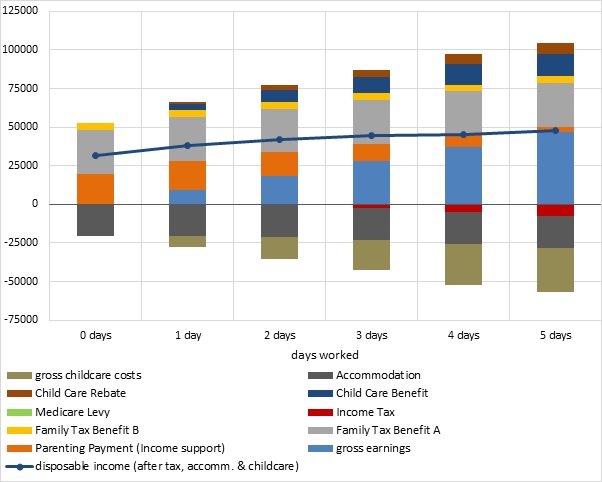

Again, we can show this table as a figure (Figure 3). The flattening of the disposable income line is, as before, quite marked.

Figure 3 Reward for working after childcare costs, sole parent wage rate $30/hr, days worked 0-5

Source: D Plunkett model

The above example assumes formal (paid) childcare. Many families do rely on informal (e.g. family) childcare to fill gaps at the start and end of days and for whole days. Even if paid for, childcare is very variable in type and cost. These cameos use the ‘policy consistent’ approach which takes the current circumstances and simply extrapolates over a year. The children and adults don’t age and there’s no adjustment for upcoming CPI increases or other changes, including school holidays which interrupt work patterns and opportunities.

So this modelling provides a generalised look at the combined impact of the various childcare schemes, not a definitive calculation of an individual’s results.

Working pays, but childcare, flexibility, and other costs are also critical

We conclude, as shown in the Tables above, that there is a financial reward from working in all cases. However, it is more attenuated after taking into account childcare costs and (often) lower female wages. In particular, working full-time is less attractive at a low wage, given the trade-offs with parenting time for a sole parent. This is consistent with the conclusions of the Productivity Commission 2015. It means that sole parents, unless they can get well paid, full-time work, often miss out on the other benefits of full-time work including superannuation contributions, paid leave, training, development and career progression.

Even with childcare and assuming there is a suitable job available, for a single parent with four kids, parenting is pretty demanding. What if they get sick? How far is work and school from home? How can after-school sport be managed? The financial costs of working such as commuting and clothes will also be challenging for Jane. There will be many situations where the financial incentives are not sufficient. Jane needs to weigh up all the costs and benefits when making a work decision.

Charts and graphs by David Plunkett.

Originally published by the Conversation.

Excellent article highlighting the precarious income problems faced by single parents, even if they can secure full-time employment

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your

weblog? My website is in the exact same niche as yours

and my users would truly benefit from some of the information you present here.

Please let me know if this okay with you. Thank you!

Hi, our blog is open access as long as you cite, happy for you to republish – ideally if you could use the link to our article at austaxpolicy.

If you are citing, you can use the “permacite” at the bottom of the article.

You’re welcome to quote with attribution.

Regards

David Ingles

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about website.

Regards

So in this scenario the “average” single parent in full time paid employment contributes 50 hours of their time per week (commuting time included) in exchange for about $15000 per year, to share amongst a family of five. AND spends every waking moment at home looking after the kids and probably cleaning when the non custodial partner takes the kids for a few hours. What is the net benefit of 50 hours of time committed to working for the average earning single man? $15000? Far far higher, at least $40000. What do they do in their non employment time? Caring for others? Relaxing? Do they have to share their earnings on nice things for their dependants? Or is their $40000 all theirs to spend on themself? If you are a single parent in Australia you and your children are always going to have significantly less, because our society doesn’t value caring, doesn’t value children and doesn’t value equality. There should be no removal of the single parent pension for working single parents until they reach 150% of the median household income for a nuclear family. There should be no removal of the SSP until the eldest child finishes high school. Because two adults available to look after the kids and share the load is a completely different parenting experience.

Hi, thanks for your substantial comment on this article which was some years ago now! (Policy settings are a bit out of date). I completely agree with you that sole parenting is a completely different experience and inadequately supported – although I would also argue that if at all possible, a parent keeping connection to the workforce and being enabled to actually earn decent income, is important for long term lifecourse wellbeing of both parent and child(ren). We showed that as a matter of basic settings, “earnings” pay, but you are correct that they pay very little. More social support for the parenting role is required – I would want to see much more earnings retained as well as the PPS

I’d love to see this same analysis done with current figures, and including repayments for a HELP debt when that starts to get deducted. The extra withholding percentage at such a low repayment threshold is a serious deterrent to increasing my hours as a single parent with 4 children almost identical in ages to those in the example. Sure I’d be making inroads into paying that debt for all my extra stress and exhaustion of juggling more working hours, but my kids would be nothing but negatively impacted. No thank you, poverty line and less stress and more time with my children, over the same poverty line and high stress and next to zero quality time with my children, that’s a no brainer for me.