Ever wondered how much of the Federal Government’s taxes never gets collected?

This is obviously an important and challenging question for government, policy makers and administrators. The amount of foregone taxes is clearly influenced by many factors—the complexity of tax laws; the state of the economy; the competency of those responsible for the operation of the tax system and, needless to say, the level of citizens’ respect for the rule of law. Research being carried out by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is revealing valuable insights into this important aspect of public finance.

The origins of modern research activity to establish the incidence and nature of non-compliance with tax laws can be traced back to the 1960s when pioneering work was carried out by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in the United States to establish its Taxpayer Compliance Measurement Program (TCMP). The centrepiece of TCMP was an audit program of over 50,000 randomly selected individual income taxpayers conducted every four years to identify errors made by taxpayers—both deliberate and inadvertent—and to quantify their overall tax impact across the broader taxpayer population. Among other things, the findings were used to develop estimates of the overall ‘tax gap’ (that is, the difference between the total amount of tax estimated to be payable and the amount actually collected) and to refine automated risk screening systems for selecting tax returns for audit scrutiny.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO), where I worked for over 25 years, explored the implications and merits of conducting its own tax gap research program in the 1980s and 1990s and I was personally involved. However, at the time ATO management chose not to undertake such research, judging that the methodologies involved were too imprecise and unreliable and too costly to implement. A particular concern was that the ATO would forego significant tax revenues by deploying scarce audit staff onto low value audit cases selected randomly, while the audits themselves would expose many innocent taxpayers to additional compliance costs. An additional consideration was the prevailing wisdom at the time that tax compliance across the tax system was “generally under control” and that any overall tax gap would not exceed 5%. These same views prevailed well into the 2000s.

Renewed interest after the global financial crisis

By 2010, the global tax gap research landscape had changed appreciably. The United Kingdom’s national revenue body had established its own comprehensive tax gap research program covering all of the taxes under its administration and similar programs were underway in countries such as Denmark and Sweden. The European Commission commissioned its own value-added tax (VAT) gap research program in 2007/08, concerned by indications of significant VAT revenue leakage within many of the 26 member states of the European Union. More generally, particularly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, an increasing number of governments around the world were taking a greater interest in assessing the effectiveness of their tax collection systems, prompting many to launch tax gap research efforts for some of their main taxes, especially their VATs.

In 2009/10, the ATO embarked on new work to identify better measures to demonstrate the effectiveness of the tax collection system and implemented a limited tax gap research effort, initially focusing on the Goods and Services Tax (GST). This research entailed use of a ‘top-down’ research methodology that relies on National Accounts data and did not require a program of random audits. Tax gap results for the GST were first made public in 2012.

In 2013, prompted by the Government and with a new tax commissioner appointed from the private sector, the ATO launched a study into the feasibility of conducting a comprehensive tax gap research program and shortly thereafter decided to commence planning its implementation. The program was to encompass all of the taxes under its administration. To assist and guide this research effort, the ATO established an expert panel of three external advisers, of which I am a member. This new research effort has seen the introduction of random audits across selected taxes and taxpayers. Full details of the program, such as methodologies and findings, can be found at the ATO’s Tax Gap page.

How big is the Australian tax gap?

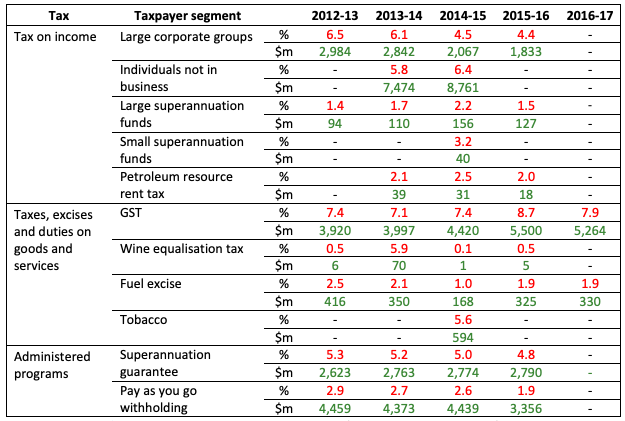

Table 1 below provides a summary of the latest published tax gap research findings.

Table 1. Australian Taxation Office: Net Tax Gap Research Findings

Source: ATO Annual Report, 2017-18, Canberra and ATO website (accessed 19 December 2018).

With findings still to be released for important areas of income tax such as small and medium businesses it is quite conceivable that total tax gap revenue leakage across all taxes (excluding administered programs) could exceed $25 billion on an annualised basis. This is a sizeable sum of revenue to loose each year and while it is not possible to eliminate the entire tax gap, the findings to date suggest some obvious areas for attention.

Perhaps the most significant tax gap finding produced to date concerns individuals’ income tax and the taxpayer segment defined by the ATO as ‘individuals not in business’; largely wage and salary earners and retirees. These taxpayers, who number just over 10 million and pay around two thirds of individual income tax, have long been regarded as the “backbone” of Australia’s tax system. This view is a result of the significant proportion of tax paid by these individuals and their perceived high levels of compliance, primarily owing to the fact that much of their income is collected by employers’ withholdings and/or subject to reporting by third parties to the ATO (such as employers, financial institutions, and government).

The ATO released its first ever estimate of the ‘individuals not in business’ tax gap in July 2018. The findings published were surprising to many, both inside and outside the ATO, and were the subject of considerable media coverage, although this quickly dissipated.

The ATO reported that this segment of taxpayers failed to pay an estimated $8.7 billion of income tax for the 2014/15 income year due to various forms of non-compliance, primarily over-claimed tax deductions, and in particular deductions for work-related expenses. This estimate of the income tax gap is equivalent to 6.4% of the amount estimated to have been properly payable for the 2014/15 income year. Significantly, random audits carried out by the ATO to develop the main component of the tax gap findings revealed a return error rate exceeding 70%. The ATO’s report also noted that, the vast majority of income tax returns for ‘individuals not in business’ are prepared by tax professionals.

As the published findings relate only to those taxpayers which the ATO classifies as ‘not in business’, they do not reflect all individual income tax. There are a further 3.5 million taxpayers classified as either ‘small businesses’ or ‘high wealth individuals’ and these taxpayers have considerably more opportunities to evade and avoid taxes, given that much of their income is subject to neither withholding nor reporting by third parties. Tax gap estimates for these taxpayers are expected in the future.

Minding the gap

Release of the ATO’s gap research findings for ‘individuals not in business’ also demonstrates another important potential benefit of tax gap research—the ability to highlight aspects of tax policy that are ineffective and/or clearly not working, pointing to the need for policy reform. For example, the issue of over-claimed work related deductions has long been recognised as a “problem to be fixed” and it was the subject of specific recommendations for reform in the last formal review of Australia’s tax system. What has been missing until 2018 is reliable quantitative evidence concerning the incidence and nature of non-compliance and associated tax revenue leakage. With deductions for work-related expenses now estimated to be overstated, in aggregate, by between 40-50% the case for policy reform is unquestionable and should now be a high priority. Simplification of this aspect of the tax system would also provide a major opportunity to fully automate the annual tax return preparation process for the majority of individual taxpayers, an outcome envisaged in numerous reviews of the tax system over the last decade, and most recently by the House of Representative’s Standing Committee on Economics.

Excellent update Richard.

Regards

Wayne

Richard, It would be interesting now to find out how big the revenue gap is at a state/territory level.