Franking credits attached to dividends are a well-known and much-loved tax credit in share investments in Australia. However, franking credits have again been in the headlines recently with a controversial draft bill proposed by the Federal Government to disallow franking credits that are funded from capital raisings. One of the reasons this bill has been proposed is to reduce the alleged “abuse” of the tax system that has adverse impacts on the Federal Budget bottom line. Indeed, this was the motivation for the Federal Labor Party’s franking credit policy that it took to the 2019 election.

Our recent study looks closely at another distortion franking credits bring to share market trading whereby market participants essentially trade with each other to share tax benefits that would have otherwise gone unused (Free version of the study available here).

How do franking credits work?

Companies pay dividends to their shareholders, which come from their profits after they have paid corporate tax. In Australia, franking credits are tax credits that recognise that companies have already paid Australian corporate tax on the dividend. They have the consequences that shareholders pay a reduced tax on dividends, or even receive a refund. Franking credits can only be used by resident shareholders, primarily individual Australian residents, Australian companies and superannuation funds.

This means franked dividends are less valuable for foreign investors as they are unable to utilise the franking credits.

An investor has essentially two choices with respect to dividends. If they own the share when the share market closes on the day before the ex-dividend day, this investor receives the dividend and franking credit. Alternatively, they can sell the share before the ex-dividend day. This latter option generally means selling the share at a higher price, but the investor will not receive the dividend and franking credit. The decision boils down to whether the investors would prefer proceeds from a share sale (and earn a capital gain) or the dividend and franking credit.

If the tax rates are the same on both dividends and capital gains, then investors would be equally happy with either option. If the tax rate on the capital gain is higher than that on dividends, then the investor would prefer to receive the dividend payment. For Australian investors, this is the situation that franking credits provide. A $1 dividend is actually worth $1.43 before income tax. Foreign investors don’t have the same preference as they are ineligible for the franking credit. This difference in preferences leads to these investors trading with each other.

The franking credit trading game

There are two quirks related to franking credits in Australia that are relevant to the “trading game” we observe in the Australian share market. First, investors need to buy and own the share for 45 days on and around the ex-dividend day to be eligible for the franking credit. This “45-day rule” is designed to stop investors from buying the share and owning it for one day to collect the tax benefits associated with the franking credit. However, there is a loophole. Investors who collect less than $5,000 in franking credits do not have to abide by the 45-day rule, so they can engage in short-term trading to capture the franking credit by owning the share for only one day.

Second, investors who have a marginal tax rate less than the corporate tax rate of 30% can receive a cash refund from the Australian Taxation Office if there are no other tax liabilities for the franking credit to offset. The refund can be as high as 43 cents per dollar of dividends. So $1 of cash dividends can actually be worth $1.43 in cash after-tax for some Australian investors. Both of the above “loopholes” encourage short-term trading by some Australian investors to capture the dividend and franking credit.

How do investors play the game?

We examine trading on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) from January 1995 to May 2016. The dataset we use allows us to identify three groups of traders by the stockbrokers that they use for their trading. Large financial institutions, including foreign investors, use an institutional stockbroker. This group also includes Australian institutional investors. We are able to disaggregate Australian retail investors (for example, “mum and dad” investors) into those using a “full-service” broker that provides tailored advice and those using a discount, or online, stockbroker, such as CommSec. We term these two groups as premium retail and discount retail, respectively.

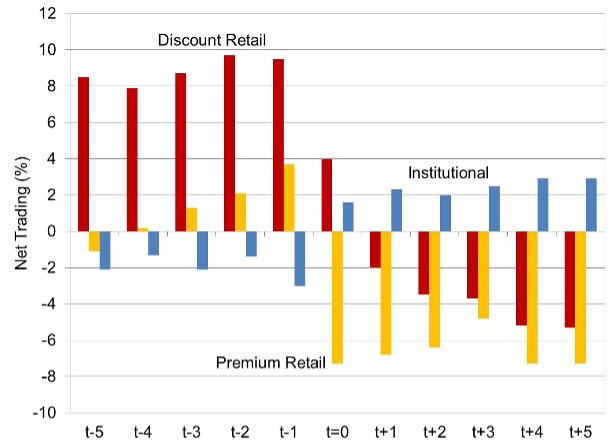

Figure 1 presents the net trading by each investor type for ten days around the ex-dividend date. The ex-dividend day is represented by t=0 in Figure 1. Net trading is measured as the dollar of purchases minus the dollar value of sales as a percentage of total trading. A positive value means that the investor type is buying more than they are selling.

We can see that investors who place a higher value on the franking credit buy shares before the ex-dividend day, with the discount retail investors have the greatest appetite for dividends and franking credits. With the exception of ex-dividend day, these investors become sellers once the share trades without access to the dividend and franking credit. Retail investors using premium, full-service brokers also engage in some excess buying before the ex-dividend day but do considerably more selling after the ex-dividend day.

On the other hand, institutional investors, which include foreign investors, take the opposite side of these trades. They sell before the ex-dividend day to avoid receiving the dividend and franking credit, and purchase shares after the ex-dividend day. We conclude that the trading behaviour of investors is generally in line with our expectations based on tax-driven preferences.

Figure 1: net trading by trader type

Who wins the game?

We delve further into the trading behaviour of discount retail investors and find that their trading becomes increasingly impatient as the ex-dividend day approaches. This leads to an increase in the trading costs paid by the discount retail investors because of their heightened demand for dividends and franking credits. This increased demand from discount retail investors pushes up share prices before the ex-dividend day and is a key part of the franking credit trading game. After the share begins trading ex-dividend, the share price falls more for stocks that were purchased by discount retail investors. Although discount retail investors gain from receiving the dividend and tax credit, they lose money because of the decline in the share price. However, they are still one of the winners of the game as the tax benefits exceed the share price decline.

Institutional investors, including foreign investors, are also winners of the game. These investors gain through trading as they can sell at a higher price before the share trades ex-dividend. The government is the loser of the game as they have effectively provided a tax benefit to discount retail traders, part of which is then transferred to institutional and foreign investors through trading. Retail investors gain from trading with institutions because they can obtain access to the tax benefits of franking credits. Institutional investors are able to make trading profits but they forgo the tax benefits, which some institutions cannot utilise.

This trading behaviour shows that even if traders are not entitled to certain tax benefits, they are able to extract value from these franking credits by trading with other market participants who can. It would seem that the current debate about franking credits that are funded by capital raisings is merely one of many areas where the dividend imputation system and franking credits can be gamed.

Any income tax system, with or without franking, which relies on an end of year assessment of income will have this issue. The same “problem” is true of trading in units of trusts or interests in partnerships. Treasury talking about the “abuse” of the franking system is rather odd considering they wanted to double tax trusts as companies without franking credits. Their preferred form of abuse would be to kill franking credits altogether – and be damned to equity or tax neutrality.