Direct democracy is becoming more and more popular all over the globe. Brexit, the Turkish constitution, or same-sex marriage and abortion laws in Ireland are widely discussed examples of national popular votes. Yet, direct democracy is also spreading on the local level. In German municipalities, more bottom-up initiatives are currently counted each year than in previous decades combined.

Relative to representative democracy, direct democracy clearly changes the mechanisms of politics. What is interesting is whether political outcomes do also change as well. For instance, tax rates: Are taxes higher or lower when popular votes replace parliaments?

Taxes are the most important source of government revenues and the key element of fiscal and economic policies. However, measuring the effect of direct democracy on tax rates is difficult because the causality may well run in the opposite direction. If citizens perceive taxes to be too high, they may react with initiatives and petitions. So, how to solve this classic chicken-and-egg dilemma?

Small German municipalities as a natural experiment

Our new paper use a specific constitutional feature in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein to isolate the causal effect of direct democracy on taxes.

The German constitution allows municipalities to have municipal assemblies of all citizens – in other words, direct democracy – in place of elected municipal councils. In the state of Schleswig-Holstein, the following rule applies to tiny municipalities: If municipalities have a population of 70 and less three years prior to the day of the next local election, no municipal council is elected for the coming legislative period. Instead, a popular assembly of all citizens legislates for the full term, which is five years.

Municipalities have no choice in the matter. The threshold of 70 inhabitants is binding. Municipalities of about the same population size of around 70 therefore have different legislature institutions. One or two inhabitants above or below the threshold make all the difference. Currently, about 25 municipalities in Schleswig-Holstein have municipal assemblies, and a similar number of municipalities that are just above the threshold of 70 inhabitants have municipal councils.

Lower property taxes under direct democracy, no effect on business taxes

Municipalities in Germany legislate property tax rates (property tax A: agriculture, and B: all other kinds of property) and business tax rates. Municipalities only decide on local multipliers, which are multiplied with a uniform basic rate and thus proportionally translate into tax rates on property and businesses. We therefore refer to local multiplier rates as tax rates.

The tax base of the property tax is the value of land and buildings at a specific census day. Property taxes affect all citizens. Tax bills are paid by the owner, but landlords are allowed to pass taxes on to tenants. Business taxes, by contrast, are levied on the profits of local firms. In 2017, property taxes generated some Euro 14 billion in tax revenues (0.4% of the German GDP); local business taxes yield Euro 53 billion (1.6% of the German GDP). Revenues from both taxes we investigate account for around one-half of total tax revenues of local governments in Germany.

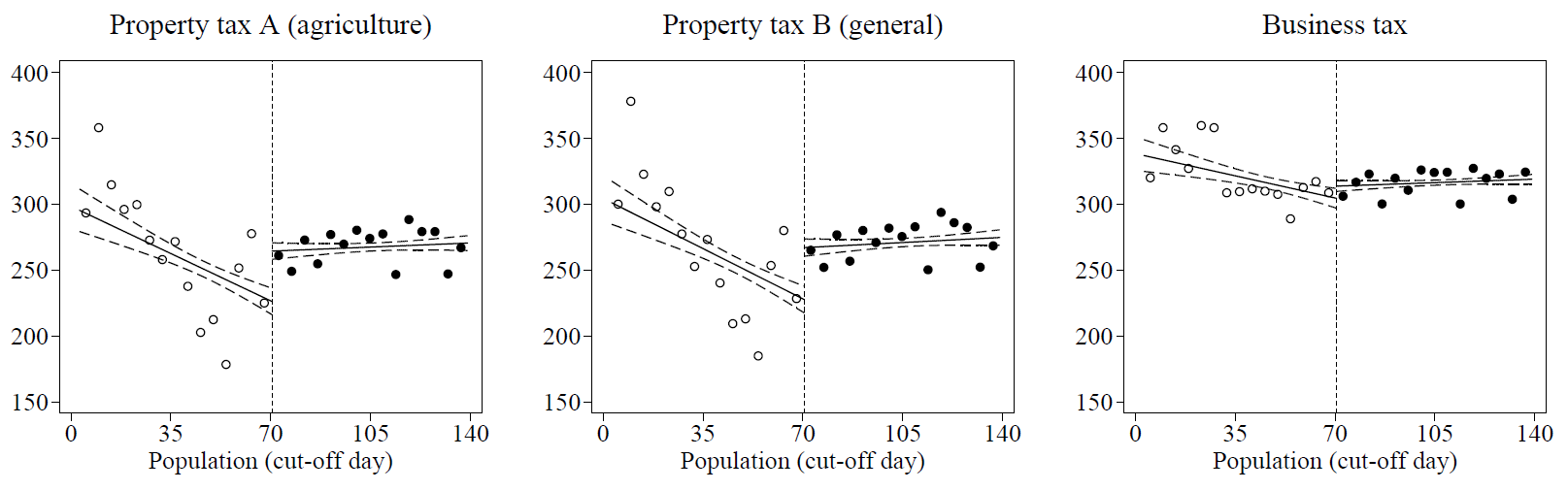

Figure 1 below shows that in very small municipalities in Schleswig-Holstein, property tax rates discontinuously jump at the threshold of 70 inhabitants between direct democracy and municipal councils. The underlying study uses a large panel data set documenting tax rates in Schleswig-Holstein for more than 40 years. Municipalities with 68 or 69 inhabitants should hardly differ from municipalities with 71 or 72 inhabitants, but they have clearly lower property tax rates of about 10 to 15 per cent. In contrast, no discontinuity is visible for business taxes.

Thus, local councils and popular assemblies tax businesses in a similar way but act differently when it comes to taxing local property.

Figure 1: Property taxes decrease under direct democracy

Note: The figure shows average tax rate multipliers of the agricultural property tax (A), the general property tax (B), and the business tax, plotted against population for German municipalities with 140 and less inhabitants (1998 to 2017). Municipalities with 70 and less inhabitants have direct democracy, municipalities with 71 and more inhabitants elect local councils. Source: Geschwind and Roesel (2021)

Other econometric approaches such as difference-in-differences or event-study estimations confirm the results. Municipalities hovering around the threshold of 70 inhabitants switched back and forth between local councils and popular assemblies several times. Property taxes well reflect those institutional changes, but not business taxes. Further robustness analyses corroborate the results. For example, in Rhineland-Palatinate – another German state with tiny municipalities but without popular assemblies – no discontinuities in tax rates are visible at the threshold of 70 inhabitants.

Mechanism

Overall, municipal assemblies tend to adopt lower rates for taxes that affect a large group of people (in this case, property taxes), and not for taxes that affect only certain special interest groups (namely business taxes).

This selectivity suggests that tax cuts observed under direct democracy work primarily through policy unbundling. Unlike in municipal elections, citizens sitting in municipal assemblies can vote separately and gradually on individual taxes, and do not have to decide on a bundle of tax policy positions on a single election day. Town meetings cut taxes selectively: the more taxes target the full population, the more robust our evidence for tax cuts under direct democracy.

Then, why do farmers benefit from direct democracy but not businesses in general? We have two explanations. First, general and agriculture property tax rates are tightly correlated (r = 0.93). For reasons of equity, municipalities often change property tax rates A and B simultaneously and by the same extent. Second, farming plays an important role in Schleswig-Holstein. Agriculture covers around three-quarters of the state’s total area, and most families are affected by both property tax rates.

The small size of the municipalities under observation provides an additional advantage to the analysis. Direct democracy has an effect even in very small municipalities, where social control of the elected representatives is likely to be very high. In contrast, the study does not provide evidence for the popular hypothesis, that direct democracy reduces ‘overspending’ by elected representatives. The size and the composition of the legislative body does also not appear to be the driving force for differences in tax policies between parliamentary and direct democracy.

Conclusion

We have shown that citizens implement lower taxes than parliaments but do so selectively. Property tax rates in small German municipalities decrease by some 10 to 15% when town meetings instead of councils design tax policies. By contrast, we do not find that business taxes change.

Our main conclusion is that direct democracy can be a useful complement to representative democracy. Citizens could overrule their elected representatives, at least sometimes. Completely different political outcomes, however, cannot be expected under direct democracy. In many cases, popular assemblies and parliaments would legislate fairly similar tax policies. Direct democracy allows citizens to design tax policies somewhat more individually than voting for a high-tax or low-tax party in elections.

Recent Comments