Public spending has mushroomed over the last two years as governments around the world struggle to cope with the health and economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic. Ultimately, governments may be forced to turn to their citizens to finance the response. But who will pay?

Previous crises have seen the burden fall onto low and middle-income wage earners through increases in regressive consumption taxes and cuts to pensions, public sector wages, and social assistance, often at the behest of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This time may be different.

The IMF recently proposed temporary tax hikes on wealthy households. This represents a sea-change from the institution’s long-held reputation for prioritising business interests over the public good. But does it represent a more permanent shift?

IMF tax advice: Old wine in new bottles?

The IMF—a lender of last resort to countries in economic turmoil—has long advocated business-friendly tax policies to stimulate economic growth. The organisation advised against high levels of corporate tax because it would scare investors, and discouraged taxes on trade on the basis that it hampers growth and increases inequality.

Instead, the IMF championed the value-added tax (VAT)—a tax on the consumption of goods and services—as an efficient instrument to meet revenue needs. According to the IMF, the VAT is efficient if it covers a broad base, is uniform across all products, and does not include exemptions.

In a new study, we investigated the links between IMF-mandated tax reforms and the evolution of taxes. Based on the IMF’s stance, we expected that where countries were under IMF lending programs, they would implement their tax policy advice. As a result, we should see tax revenues on goods and services increase, but revenues from trade taxes decline.

How the IMF alters the composition of tax revenue

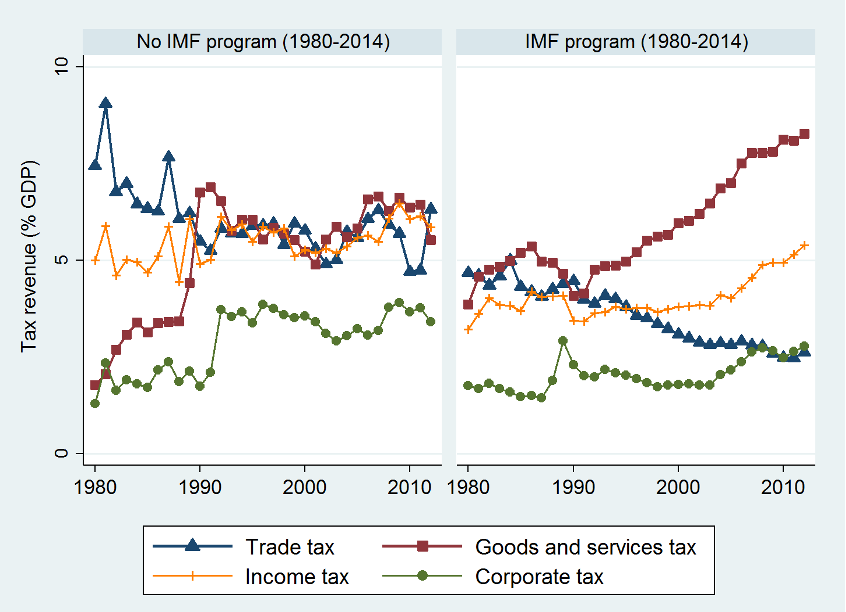

We collected data on taxation from the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) and combined it with our data on IMF conditionality from the IMF Monitor database. We then compared tax revenues between countries that underwent at least one IMF program in the past three decades with countries that never had an IMF program. We found that IMF borrowers experienced increases in goods and services tax revenues but a decline in trade tax revenues, consistent with our priors. For non-IMF borrowers, the composition of tax revenues remained unaffected (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of tax revenues by IMF exposure

To examine these patterns further, we conducted regression analysis for 100 developing countries from 1993 to 2013, controlling for known confounders. We confirmed that IMF programs increase goods and services tax revenues but decrease revenues from trade taxes. These patterns were particularly pronounced where IMF programs included explicit policy conditions on taxation.

Yet, we further showed that IMF programs did not affect total tax revenues. These results suggest that IMF policies alter the structure of tax revenues in developing countries, without bringing net positive effects for total tax revenue.

Why the VAT is inappropriate for developing countries

Development economists point out that while a tax system with heavy reliance on VAT may be optimal for advanced economies, it is inappropriate for many developing countries—as famous economists like Joseph Stiglitz argue. First, it may have adverse distributive impact, as the set of instruments for redistribution is more limited in developing countries. Second, it may be less conducive to economic efficiency, because the presence of a non-taxable informal sector distorts allocation decisions. Indeed, when a large part of the economy is informal, the VAT is not applied universally, but a trade tax may be. Third, the VAT is less corruption-resistant given that record-keeping systems are not well-advanced in developing countries.

Even in light of these serious doubts about the VAT, the IMF does not seem to be willing to change course. Only in September last year, the IMF celebrated its ‘world-wide leading role’ in spreading the VAT. A senior IMF official stressed the importance of having ‘few or no exemptions or other special treatments… [including] on items on which the poor spend a large proportion of their income’ and maintained that expenditure measures such as targeted social protection schemes were more efficient in addressing these concerns. IMF operations are in line with such thinking: A study by Eurodad found that of 59 IMF programs agreed during the Covid-19 pandemic that the study analysed, 39 included commitments to increase the share of indirect taxes, particularly VAT, in total government revenues.

What needs to be done

The IMF is correct in warning that ‘the economic shock triggered by the pandemic could undermine public attitudes to the fairness of taxation and welfare systems and lead to social unrest.’ But introducing a temporary tax on the better-off members of society is not sufficient to quell public unrest.

Indeed, the fixation of IMF leadership on this instrument deflects attention away from a more pressing issue—the need to change its view about the regressive VAT that places a disproportional tax burden on the poorest and most vulnerable members of society.

Recent Comments