Income tax progressivity has been an entrenched characteristic of Australia’s personal income tax system, meaning that the average rate of tax (the total tax paid as a percentage of income) increases with taxable income (see Peter Varela’s TTPI Policy Brief). As commentators have noted, the Government’s three-stage Personal Income Tax Plan (legislated in 2018 and 2019), particularly Stage 3, undermines progressivity in Australia’s personal income tax system.

In the 2020-21 Budget, there was a compelling case for modifying the Personal Income Tax Plan and effecting a more equitable distribution of tax benefits. The economic climate of 2020 has more harshly impacted lower-income individuals who dominate service industries devastated by COVID-19 restrictions, with modelling by the Grattan Institute indicating that the ‘lower a person’s income, the more likely it is that their job is at risk as a result of COVID-19.’ We highlight that the 2020-21 Budget does not address inequity in the Personal Income Tax Plan, despite a pressing need for revision. This has significant implications for women, who are among those ‘hit hardest’ by COVID-19 restrictions, because there are virtually no tax benefits at the level of female median income.

A recap of the Personal Income Tax Plan

The legislated Personal Income Tax Plan involves significant changes to thresholds and tax rates, and the (temporary) Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO). Stage 1, which commenced in 2018-19, implemented LMITO and was to apply for four income years (ending 2021-22). Although claimed to benefit both low and middle income earners, the LMITO was far more beneficial for middle income earners, as noted in Austaxpolicy’s 2019 Budget Forum.

Stage 2, initially legislated to take effect from 2022-23, involves increasing the Low Income Tax Offset (LITO) from $445 to $700 and two changes to income tax thresholds: increasing the upper threshold of the first marginal tax rate of 19% from $37,000 to $45,000 and increasing the upper threshold of the second marginal tax rate of 32.5% from $90,000 to $120,000. Stage 3, which takes effect from 2024-25, involves a substantial flattening of the income tax system, with a new second marginal rate of 30% (to replace the existing rate of 32.5%) that applies to taxable incomes between $45,000 to $200,000.

Budget 2020-21: bringing forward Stage 2

In the 2020-21 Budget, the Treasurer announced bringing forward Stage 2 of the Personal Income Tax Plan two years to 2020-21, and a continuance of the LMITO in this income year. In the Budget measure, Stage 2 would now comprise four income years (from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2024).

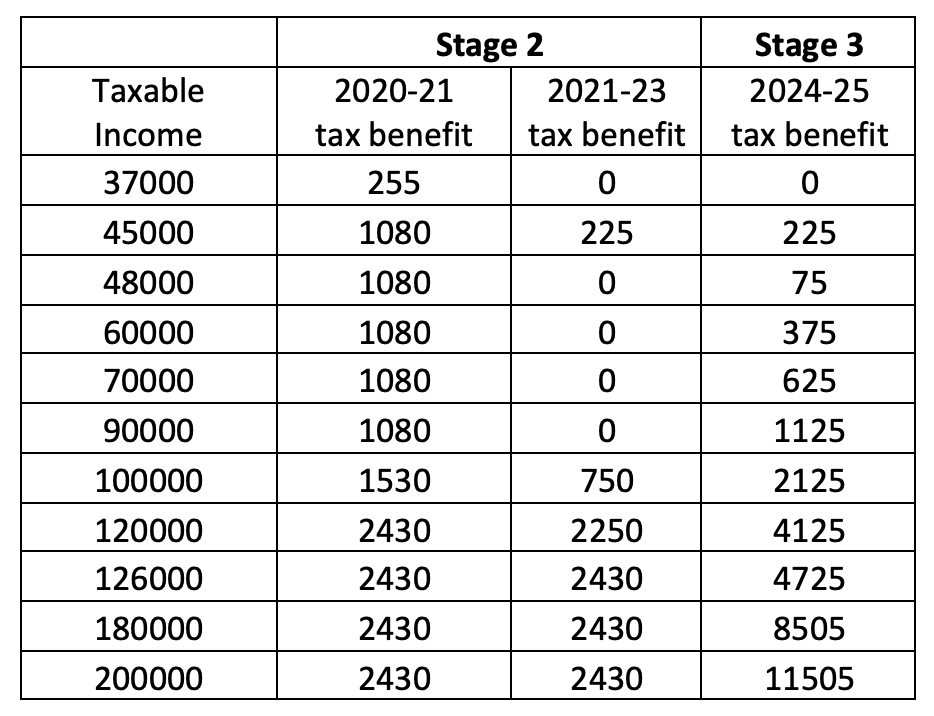

The main consequence of this is to bring forward income tax cuts that primarily benefit taxpayers earning $120,000 or more. Table 1 below shows the net tax benefit of Stage 2 and Stage 3 measures compared to 2019-2020 at various taxable income levels after taking account of all tax rate changes as well as the LITO and the LMITO (most income levels below correspond with thresholds relevant for tax rates or offsets).

Table 1 – Dollar Tax Benefit (compared to 2019-20)

As shown in the second column, the retention of the LMITO in 2020-21 (not originally part of Stage 2) provides a one-off tax benefit for middle income earners with a considerably smaller benefit to lower income individuals at taxable incomes of $37,000 (or less).

However, as shown in the third column, in the following three income years of Stage 2, most income levels up to $90,000 are no better off compared to their 2019-20 position, and some are worse off compared to 2020-21 (with disparities in tax benefits between high income earners and other taxpayers heightening in Stage 3).

How does the Personal Income Tax Plan undermine progressivity?

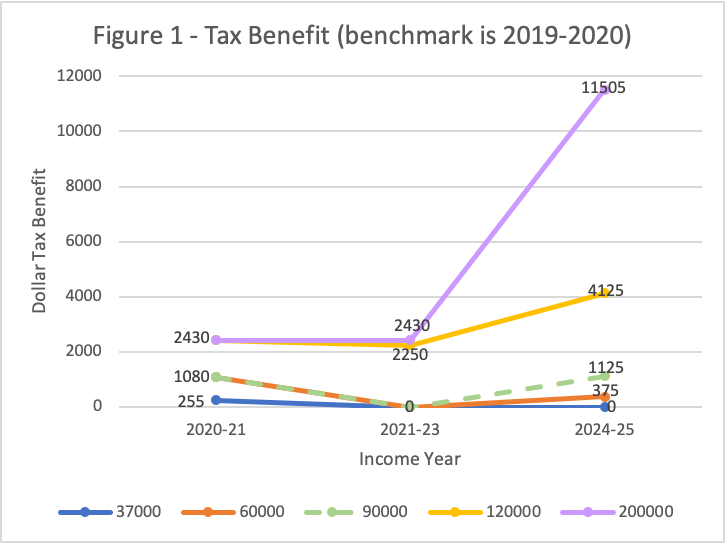

By translating Table 1 into Figure 1 below (where each of the five lines corresponds to five taxable income levels, as indicated), it is clear that Stage 3 (to apply from 2024-25) is most clearly associated with a substantial erosion of progressivity. But there is also considerable inequity in the Stage 2 measures.

The Government’s Budget papers (from 2019) describe Stage 2 as permanently ‘locking in’ the tax benefits of LMITO from Stage 1 (see at 1-11). While it is true that the tax benefit from LMITO would continue for past LMITO recipients (both under the legislated plan and the 2020-21 Budget measure), the effect of ‘locking in’ the benefit via a threshold change undermines progressivity because it confers the value of the LMITO benefit to all taxpayers who earn above the relevant threshold.

The tax benefit associated with the increase to the upper threshold of the 19% rate ($45,000-$37,000 x (0.325-0.19)) exactly matches the full value of LMITO of $1,080. All taxpayers (who earn above $45,000) are conferred the benefit, including the very highest income earners. The second threshold change that extends the 32.5% bracket to $120,000 only benefits taxpayers earning $90,000 or more.

To cleanly illustrate the significant tax benefits to high income earners from Stage 2, we can focus on persons with taxable incomes above $126,000 (who are not eligible for any part of LMITO), all of whom obtain a $2,430 tax benefit in the four income years of Stage 2, compared to their 2019-20 position (see Table 1). This benefit can be decomposed into $1,080 (which matches the value of LMITO, but conferred via the first threshold change) and a further $1,350 from the second threshold change (i.e. $120,000-$90,000 x (0.37-0.325)).

By comparison, lower- and middle-income earners benefit considerably less and not at all in many cases (see above, Table 1 and Figure 1). In 2020-21, persons with a taxable income between $48,000 to $90,000 obtain a one-off benefit of $1,080 in the amount of their LMITO entitlement, with a much smaller benefit of $255 at an income of $37,000 (from $37,000 to $48,000, the benefit ranges from $255 to $1,080; from $45,000 to $48,000, the benefit happens to match $1,080 and this is due to the effect of the first threshold change).

In the following three income years (2021-22, 2022-23 and 2023-24) when LMITO is to be discontinued, with one small exception, there is no tax benefit at all for taxable incomes of $90,000 or less compared to their 2019-20 position (see Table 1). Taxable incomes between $45,000 and $48,000 get a modest benefit (a maximum of $225 at $45,000) because the tax benefit conferred by the increase to the upper threshold of the 19% rate (which matches the full LMITO entitlement of $1,080) is superior to their previous partial LMITO entitlement ($855 at $45,000).

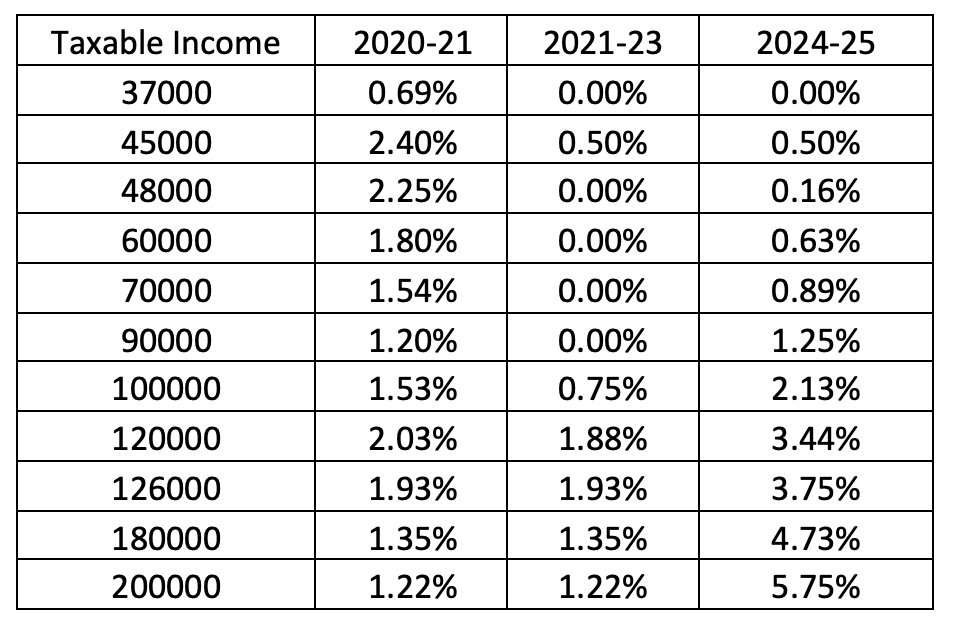

The progressivity impact of Stage 2 and Stage 3 is captured in Table 2 below, which shows the decline in average tax rates across income levels from $37,000 to $200,000 (using 2019-20 as the benchmark).

Table 2 – Percentage Decline in Average Tax Rates (compared to 2019-20)

As shown, for taxpayers with taxable income up to $90,000 there is no decline in average tax rates in 2021-23 and very modest declines from 2024-25 (Stage 3) for most incomes below $90,000. According to the most recent ATO data available (from 2017-18), the annual median taxable income in Australia is $45,882 (average annual taxable income is $61,217), and the approximate decline in the average tax rate at this income level is only 0.5%. The decline in average tax rates steadily increases for higher taxable incomes, ranging from 3.44% to 5.75% as income increases from $120,000 to $200,000.

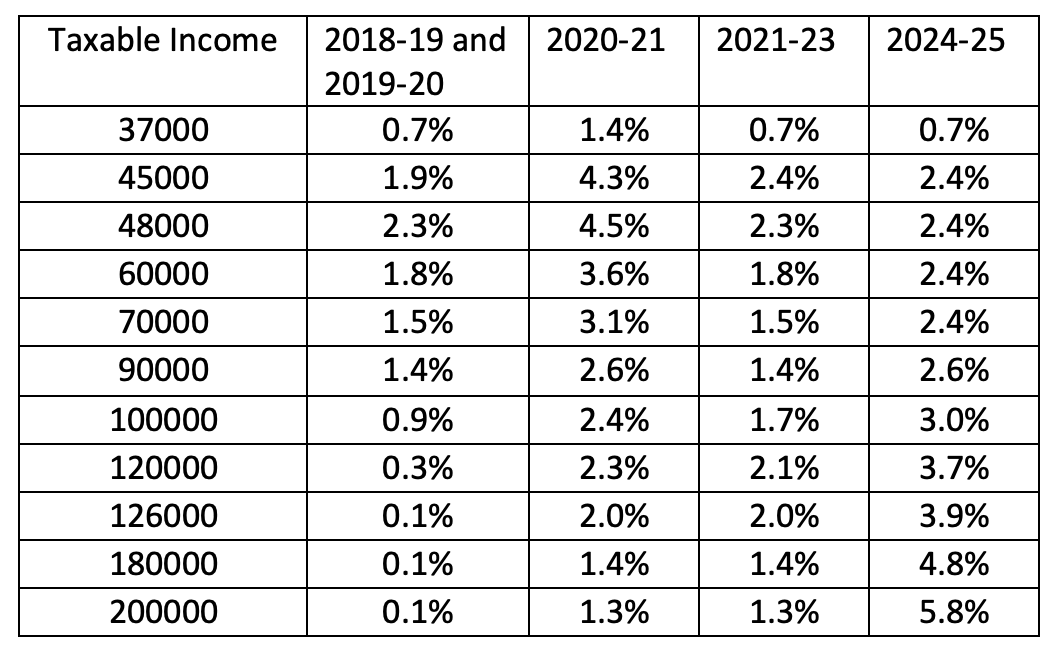

Even if the reference year is changed to 2017-18 (preceding Stage 1 measures) on the reasoning that the 2019-20 income year already incorporates benefits to at least middle-income earners, there is still a significant erosion of progressivity in Stage 3 as shown in Table 3 below. However, the devastating economic circumstances of 2020 now make the 2019-20 income year a natural benchmark for evaluating the income tax effects of Stage 2 and Stage 3.

Table 3 – Percentage Decline in Average Tax Rates (compared to 2017-18)

The lack of a tax benefit at a taxable income of $37,000

A specific, glaring source of inequity is the lack of a tax benefit for persons with a taxable income of $37,000, which is a relevant threshold in the tax rate schedule, LITO and LMITO.

As shown above (see Table 1 and 2 and Figure 1), persons at a taxable income of $37,000 receive no tax benefit at all in 2021-2023 (most of Stage 2) and Stage 3 compared to their current position in 2019-20, and (as shown in Table 3 above) have received only very modest benefits in Stage 1 (2018-19 and 2019-20) compared to middle income earners (at $37,000, the LMITO entitlement is $255 and the combined LITO and LMITO entitlement is only $700, whereas those at $48,000 receive the maximum combined entitlement of $1,360).

This is a point of policy importance. According to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics data more than half (54.6%) of women in Australia work part-time, and a taxable income of $37,000 is close to median female taxable income ($39,000, in the most recent ATO data).

As widely noted, women have been severely affected by the economic consequences of COVID-19. Indeed, as part of Budget 2020-21 policy initiatives, the Government has released a 2020 Women’s Economic Security Statement which signals a commitment to ‘repair and rebuild women’s workforce participation and further close the gender pay gap,’ acknowledging women ‘are more likely to be part-time or casual workers and highly represented in hard-hit industries’ (see at p.11 and p.14). However, this policy document does not examine tax incentives and female labour participation in any meaningful way. It merely provides a generic summary of tax cuts in the 2020-21 Budget and illustrates claimed tax benefits by using a hypothetical example set in 2020-21 (which contains one-off benefits) with a woman earning well in excess of median female income (at p.18).

Conclusion

Overall, the Personal Income Tax operates inequitably because higher income individuals are consistently better off in Stage 2 and Stage 3 compared to their 2019-20 position, whereas lower income individuals are no better off apart from the one-off benefit in 2020-21. In particular, delivering a definite and persistent tax benefit to taxable incomes of around $37,000 should be included in the policy response to incentivise female labour force participation.

Other Budget Forum 2020 articles

Blink and You’ll Miss It: What the Budget Did for Working Mums, by Miranda Stewart.

Economic Stimulus through a Gender Lens: Why the Budget Did Not Deliver, by Helen Hodgson.

Training Subsidies and Market Failures, by John Freebairn.

Getting Coherence into the Equity Debate – Part 3, by Andrew Podger.

Getting Coherence into the Equity Debate – Part 2, by Andrew Podger.

Getting Coherence into the Equity Debate – Part 1, by Andrew Podger.

What Has Volunteering Got to Do With the Budget? By Sue Regan.

Talk of Aspiration Is Not Borne Out in Federal Budget Papers, by John Hewson.

Asymmetric Taxation of Business Income and Losses, by John Freebairn.

Economic Security for Older Partnered Women and Widows: Fixing Gaps in Australia’s Superannuation System, by Monica Costa, Helen Hodgson, Siobhan Austen and Rhonda Sharp.

Heroic Assumptions in Budget Omit One Major Threat: A Global Debt Crunch, by John Hewson.

Dream Budget or Not? by Shumi Akhtar.

Will Instant Asset Write-Offs Boost Jobs? by Michael Coelli.

It’s Not the Size of the Budget Deficit That Counts; It’s How You Use It, by Steven Hamilton.

Looking for Bold Reform? Get Rid of Payroll Taxes, by Robert Breunig.

It’s Time to Meet Key Social Policy Challenges in COVID Recovery, by John Hewson.

Meet the Liveable Income Guarantee, a Budget-Ready Proposal That Would Prevent Unemployment Benefits Falling off a Cliff, by John Quiggin, Elise Klein and Troy Henderson.

COVID-19 Strengthens Australians’ Belief in the Fair Go, Government Should Support the Vulnerable, by Emma Dawson.

Recent Comments