One of the most well-established practical observations in economics is that when we give an unemployed person a payment, it tends to delay their return to work.

Rightly or wrongly, it is an argument used to justify a rate of JobSeeker one third below the pension.

How well does the finding apply if the payment is a A$10,000 lump sum delivered at the height of a pandemic, funded through a corresponding reduction in someone’s retirement savings?

That is what we and colleague Timothy Watson at the ANU Tax and Transfer Institute set out to examine as part of new research.

The early release of super

By way of recap, the COVID early access to superannuation announced on Sunday 22 March 2020 was available to people who faced a 20% decline in working hours (or turnover for sole traders), were made unemployed or redundant, or received JobSeeker or related benefit.

These people were able to take out lump sums of up to $10,000 between April and June 2020, and a further $10,000 between July and December 2020.

The maximum $10,000 represented approximately 13 weeks of (effectively doubled)

unemployment benefit, and eight weeks of the minimum wage.

In essence, the government offered a bargain like this:

You know those superannuation savings you probably won’t be able to access until your late 60s? Well, life’s scary and uncertain. So here’s a chance to take out $10,000! You can only make use of it in the next three months though. That said, there’s a second chance in the next six months if you still qualify.

Three million Australians responded, close to one fifth of the population aged 16 to 65 with super accounts. Seven in ten took out the maximum $10,000.

This made the $38 billion withdrawn the second largest stimulus measure in 2020 behind the $88 billion JobKeeper wage subsidy, and one of the biggest stimulus measures in Australian history.

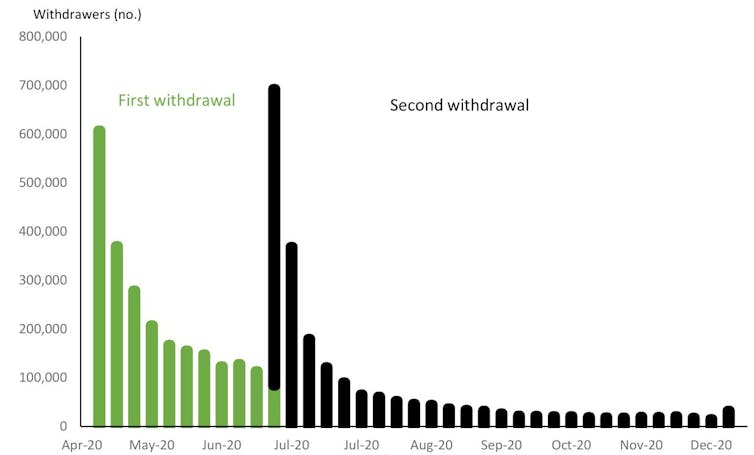

Weekly applications: a rush both times

Withdrawals delayed the return to work

We were given access to de-identified administrative records that link takeup of the offer to the length of stay on the unemployment benefit.

Focusing on the half a million Australians who arrived on payments as economic and social conditions deteriorated in the initial months 2020, we compared the length of time on benefits of the more than 230,000 who took advantage of early release with the 300,000 individuals who did not.

We calculate that the withdrawers who completed their time on benefits by June 2021 (about 162,000) spent about seven weeks longer on benefits than similarly-placed recipients who didn’t withdraw.

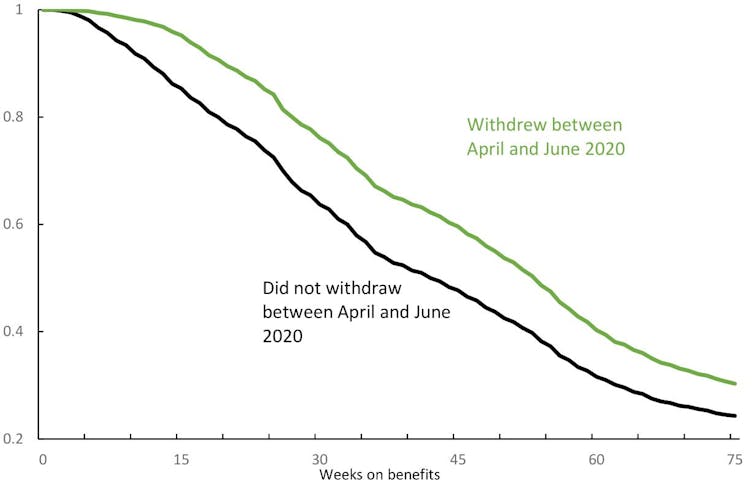

The chart below shows the story. A big gap in the rate of exit from benefits opens up between those who took advantage of the opportunity to access their super and those who did not, with those who used more likely to stay on benefits.

The gap grows over the first 13 weeks on benefits, then narrows only slowly, taking 18 months to come close to closing.

Probability of staying on benefits, first lot of withdrawals

Interestingly, those who withdrew are also those we would ordinarily have expected to spend less time on benefits.

They tended to have higher pre-COVID wage and superannuation balances, and were more likely to be married, male, and have children.

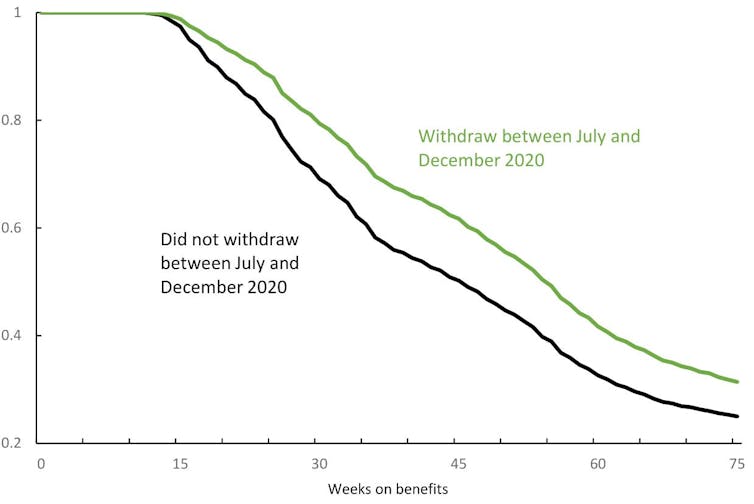

Probability of staying on benefits, second lot of withdrawals

Factor in an extensive collection of population characteristics into our estimates, and – after a battery of sensitivity and robustness checks – we found that the large lump sums had large effects in extending benefit tenures.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Being pushed into work too soon can push people into the wrong jobs. But we find no evidence that those who stayed out longer because of withdrawing their super found higher-paying jobs.

Implications

From today’s standpoint, two years on, with unemployment the lowest in almost 50 years, it is clear that early access to super delayed rather than prevented unemployed Australians returning to work.

But that mightn’t have been the case if the early withdrawal measure had been introduced at a different time, when the labour market wasn’t about to pick up.

It is also clear that the measure helped people when they needed it, although it is too early to assess its impact on their rest-of-life incomes and super balances.

A further thing we can say is that early withdrawals should not be considered private “off balance sheet” matters without an impact on public finances.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation puts the cost of additional benefit payments to the 162,000 withdrawers we studied at $600 million, a figure that might climb to $1 billion if applied to everyone who used the scheme.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Years ago I was Secretary of the IDC on Retirement Incomes. I argued that superannuation contributions should be deductible up to the whole of personal exertion income. no taxation of superfund earnings, no compulsory preservation but benefits only withdrawable as as a fully taxable and $1 for $1 income tested term certain annuity based on life expectancy or a pension. In short, super was a form of forward income averaging and should be allowed to replace unnecessary reliance on tax financed welfare payments. In former days, one’s children and one’s savings were one’s retirement plan and sensible people still see that children offer what the State never can in one’s old age.