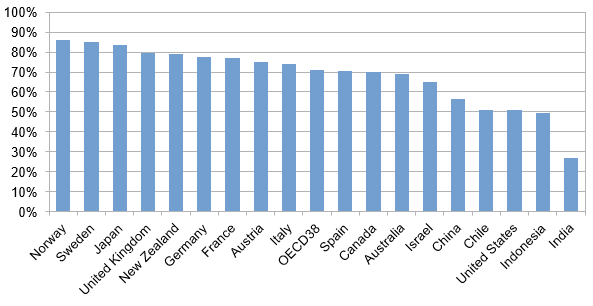

Health risk is difficult to insure via private insurance markets. Information asymmetries between buyers and sellers of private insurance plans cause adverse selection and moral hazard which leads to high premiums and leaves a large share of the population uninsured. Market failure is one of the main justifications for government involvement in the health insurance sector. As a consequence, today governments are the largest providers of health insurance in almost all developed countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Health expenditure from public sources

Source: OECD 2021

Health insurance system designs differ across OECD countries. The most common design includes basic universal public health insurance (UPHI) in combination with a supplemental private health insurance component. In this system, private health insurance facilitates better access to private clinics, more luxurious care such a single-bed hospital room, or services that are not covered by the existing public health insurance system such as certain types of vision or dental care. The Medicare systems in Australia and Canada are typical examples of this design.

The United States system is somewhat of an outlier as the private health insurance component plays a more prominent role. Private health insurance is largely provided through employers. Employer-provided health insurance started after the 1942 Stabilization Act imposed rigid wage controls in order to fight inflation during World War II. Employers, in an attempt to compete for scarce workers, began adding group-rated health insurance to the non-wage compensation packages. To this day, premiums of employer-provided insurance are tax deductible.

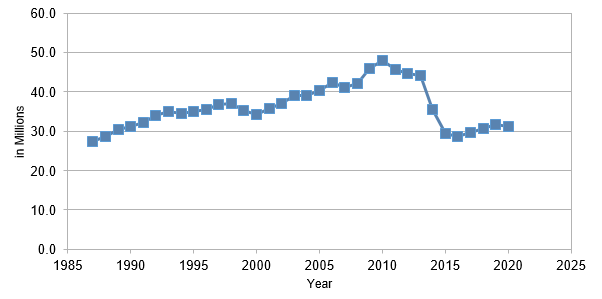

The main parts of the public health insurance component were introduced via the Social Security Act in 1965. The two largest programs are Medicare which focuses on the retired population and Medicaid which insures individuals with low income. Overall, this mixed health insurance system leaves millions of Americans without health insurance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of uninsured

Source: National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA)

In our recently published study, Jung and Tran (2022), we explore different avenues to improve the current system using a large scale dynamic general equilibrium model that simulates the main institutions of the US healthcare sector. We focus both on the overall welfare benefits but also on the public finance aspects of expanding either the public or the private health insurance components of the current system.

Expanding US Medicare

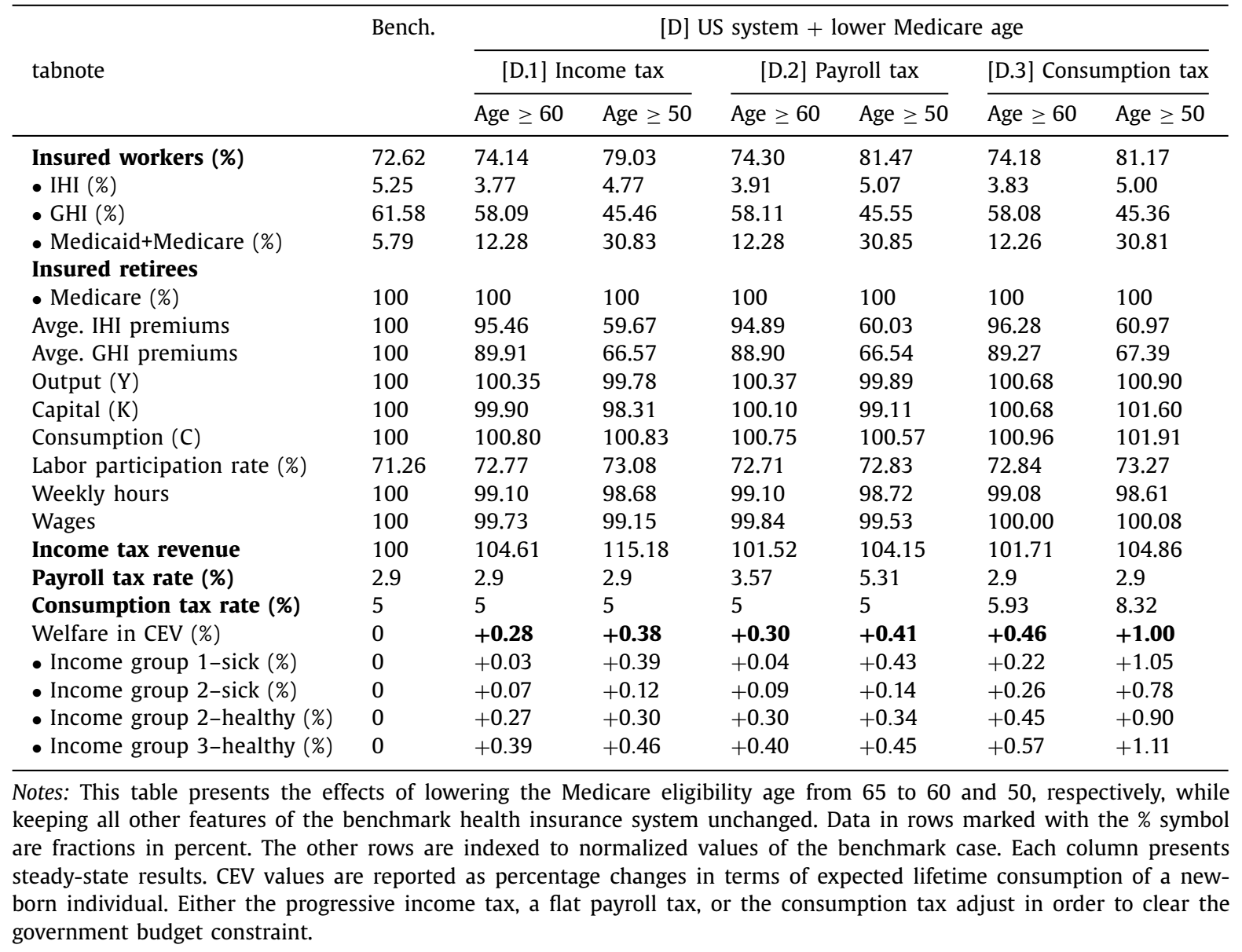

We first simulate lowering the eligibility threshold of US Medicare from currently 65 to 60. The goal of this policy reform is to insure more of the vulnerable older workers that lose their job due to health issues or skill obsolescence. Since the majority of workers in the US gets their health insurance from their employers, many of these individuals lose their health insurance at a time when they become increasingly vulnerable to health issues due to their age.

Our simulation shows that this Medicare expansion not only benefits the newly eligible workers but also younger workers. As the older cohort leaves the private health insurance pool and moves into Medicare, the remaining pool of individual with private health insurance becomes younger and their expected health expenditures decrease. As a result, private health insurance premiums decrease which directly benefits younger workers. This experiment demonstrates that the expansion of Medicare can generate welfare gains and improve social insurance at a moderate cost of higher taxes. Slightly larger welfare gains can be achieved by lowering the threshold further down to age 50 (see Table 1).

Table 1: Expansion of Medicare

Universal Public Health Insurance (UPHI)

Universal, single payer, public health insurance is a popular policy proposal pushed for years by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. While the details of the proposals have changed over time, the core idea has always involved government-provided health insurance for the entire US population financed by taxes similar to the Medicare system in Australia or Canada.

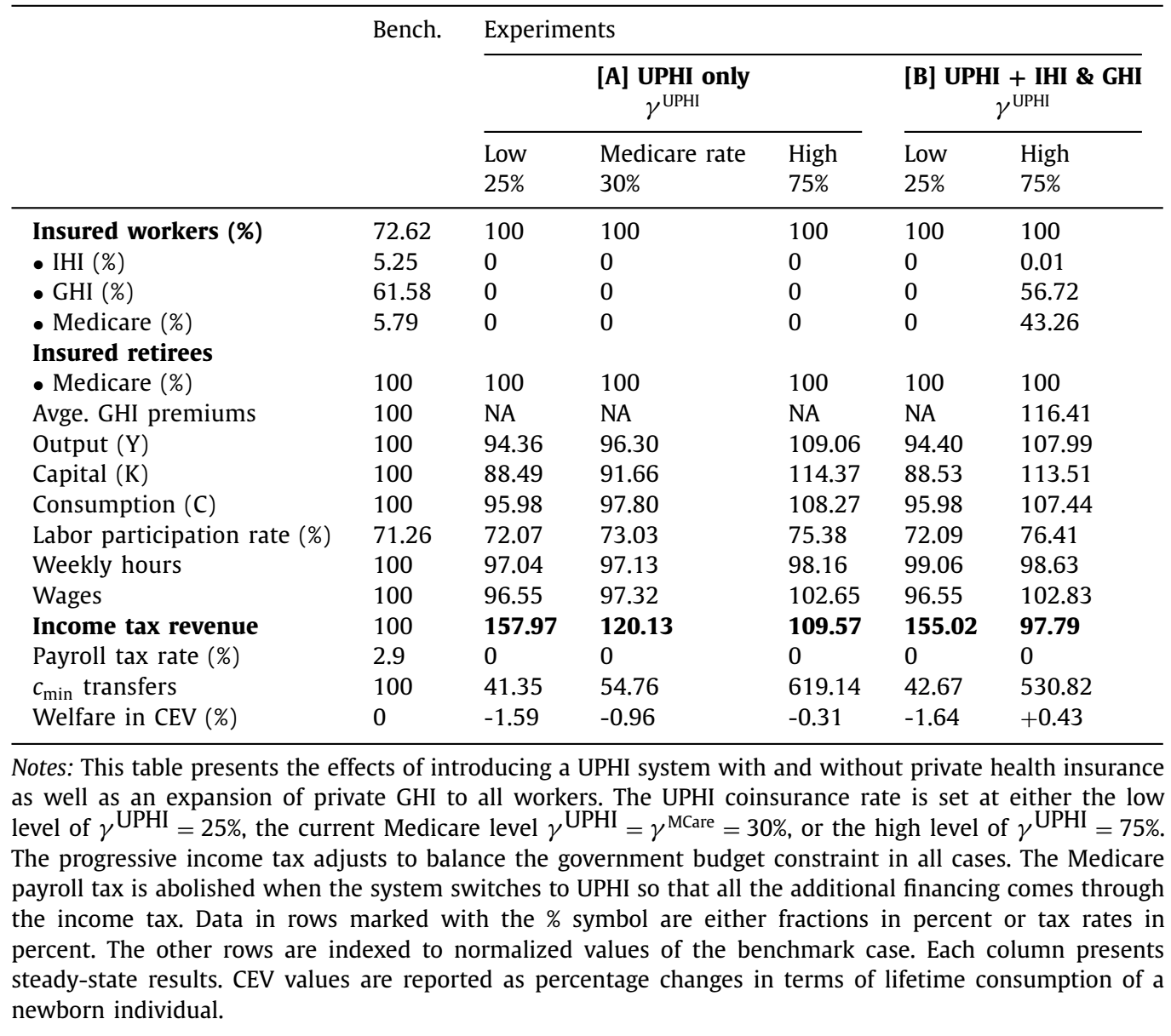

In the context of our model, the introduction of a UPHI program leads to a significant reduction in labor supply and household savings due to crowding-out effects (see Table 2). The latter is the result of individuals moving from self-insurance via savings to relying on government health insurance. As taxes rise to finance the UPHI system, the associated tax distortions reduce the production capacity of the economy and lead to output losses and therefore lower income. All these effects in isolation would decrease welfare.

However, the UPHI system also eliminates adverse selection issues and improves risk sharing which both lead to welfare gains. Especially low income and sick individuals benefit from the UPHI system.

Overall, our results indicate that welfare losses caused by “bad” incentive effects dominate welfare gains due to “good” insurance and redistribution effects. This result strongly depends on the assumption that the generosity of the new UPHI system is similar to the current US Medicare system. This generosity is guided by the coinsurance rate (the fraction of the medical bill that the individual pays) which is set to 30 per cent.

Table 2: Universal Public Health Insurance (UPHI)

The generosity of the UPHI system has important implications for the overall welfare outcome of the reform. By lowering the coinsurance rate of UPHI the government can shift the financial burden of medical care from high risk individuals to the tax paying public. On the other hand, higher coinsurance rates require households to contribute more out-of-pocket to finance their health expenditures and leaves them more exposed to idiosyncratic health expenditure risk. If the UPHI coinsurance rate is set to a higher level than the current Medicare coinsurance rate, welfare gains can be achieved.

We finally solve for the optimal coinsurance rate that maximises the overall welfare outcome. This coinsurance rate is relatively large and ranges from 42.6 per cent to 54 per cent, depending on the specific tax that is used to finance the UPHI system.

UPHI with Private Health Insurance options

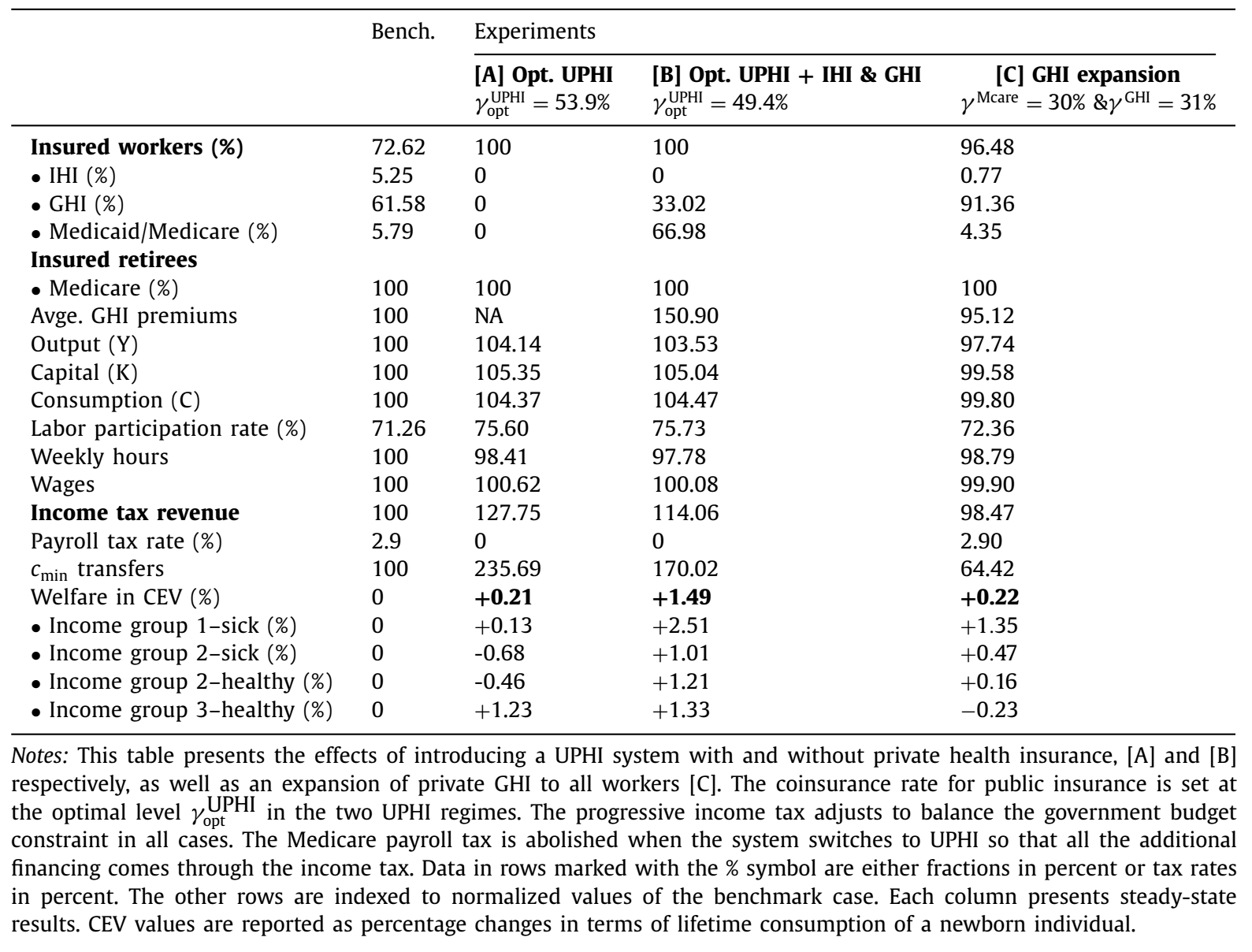

The tax burden caused by the UPHI system can be lowered by allowing workers to switch from public to private insurance. This decreases the size of the government-run UPHI system and the associated tax burden (see column [B] of Table 3).

Table 3: UPHI and Private Health Insurance

The optimal UPHI coinsurance rate in this scenario is around 49 per cent if the progressive income tax is used to finance the UPHI system. At this rate, about a third of workers decide to stay in private group health insurance (GHI) plans which lowers the fiscal cost of the UPHI expansion and income tax revenue increases by “only” 14 per cent as opposed to 28 per cent in the UPHI reform without any private insurance options. Overall, the UPHI system in this environment leads to larger welfare gains. More importantly, the optimal UPHI system with private health insurance plans results in welfare gains for all income groups, which translates into higher overall welfare gains compared to the optimal UPHI system with no private options.

Finally, we explore options to strengthen the private health insurance component of the current US insurance system and simulate a government mandate that would force all employers to offer GHI to their employees (see column [C] of Table 3). This removes the risk of a worker being paired with an employer that does not offer GHI as is often the case under the current US system.

We find that this reform leads to a large increase in the fraction of workers with GHI from 62 per cent to about 91 per cent. The experiment shows that mandating GHI offers to all workers and allowing premiums to be tax deductible can help reduce adverse selection. In addition, while offering GHI to all working age individuals increases the labor force participation rate, it does lower the average hours worked and the capital stock. The latter is a direct result of workers moving from self-insurance via household savings to tax-deductible private health insurance plans. Overall, the reform leads to moderate average welfare gains.

This experiment demonstrates that further regulation of private health insurance markets (namely, mandating GHI offers for all workers) can generate welfare gains and improve the social insurance role of the US health insurance system.

Policy implications

Our analysis provides new evidence in support of extending Medicare to address the failure of the current health insurance system in the US. We show that even a radical reform that introduces a Medicare-for-all system, namely Universal Public Health Insurance (UPHI), could potentially be welfare improving in the long-run, especially for low-income individuals. However, we do calculate large welfare losses for high income individuals who are the main beneficiaries of the current employer-sponsored, private group health insurance scheme. These opposing welfare outcomes imply political challenges for more comprehensive health insurance reform plans such as UPHI. Adding group health insurance as private options to the UPHI system would mitigate welfare losses of high income individuals.

Journal article

Juergen Jung and Chung Tran. 2022. “Social Health Insurance: A Quantitative Exploration”, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control. Vol. 139.

Recent Comments