At what point is there ‘too much of a good thing’ with crisis cash transfers?

This is an important question for future economic shocks, whether due to pandemic or other trigger. We raised it in a recent Australian Economic Review paper when we examined Australia’s economic policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australia’s emergency cash transfers during the pandemic

During the early stages of COVID-19 in 2020 the Australian federal government temporarily expanded the level and types of fiscal relief available to the working-age population.

Three of the largest measures were cash transfers targeted at individuals:

- an $88 billion wage subsidy;

- early access to $38 billion in withdrawals from private pension accounts; and

- $52 billion in supplemented benefit payments to the unemployed, students and parents.

We use the term ‘transfer’ here as a generic label for all three programs even though the pension account program allowed individuals to access money from their own superannuation accounts.

These emergency cash transfers were in place for a year, designed to alleviate hardship at a point of acute stress, and would replace a portion of the pre-pandemic earnings of healthy individuals who found their income-earning capacity suddenly and unexpectedly constrained.

To examine the scope and distributional dimensions of these three emergency COVID-19 cash transfers, we combine administrative data on weekly Australian wage earnings with the universe of administrative program records relating to these transfers.

A two-tier welfare system with unprecedented scope and scale

What we found around the nature of income redistribution during the early part of COVID-19 can be summarised in five stylised facts.

First, the scale of fiscal intervention was extensive. In total, 6.5 million working-age Australians (42 per cent of working-age population) accessed the three programs over a 12-month period.

Second, the level of transfer per recipient was substantial. The median recipient had 46 per cent of weekly pre-COVID-19 wages replaced by the transfers.

Third, there was significant heterogeneity in program receipt. We paint a picture of a two-tier, 12-month pandemic welfare system:

- A poverty-alleviating income floor through benefit payments was disproportionately accessed by workers in low-earning occupations and welfare recipients.

- The more generous JobKeeper wage subsidy and superannuation withdrawals boosted incomes and provided employment certainty. They were targeted more towards the middle and upper middle segments of the income distribution.

Fourth, together, the programs produced a strong, short-lived, shift in the income distribution. There was large movement out of low levels of income into the lower-middle and upper middle segments of the income distribution. By April 2021, however, the weekly income distribution once again closely resembled the pre-COVID-19 income distribution.

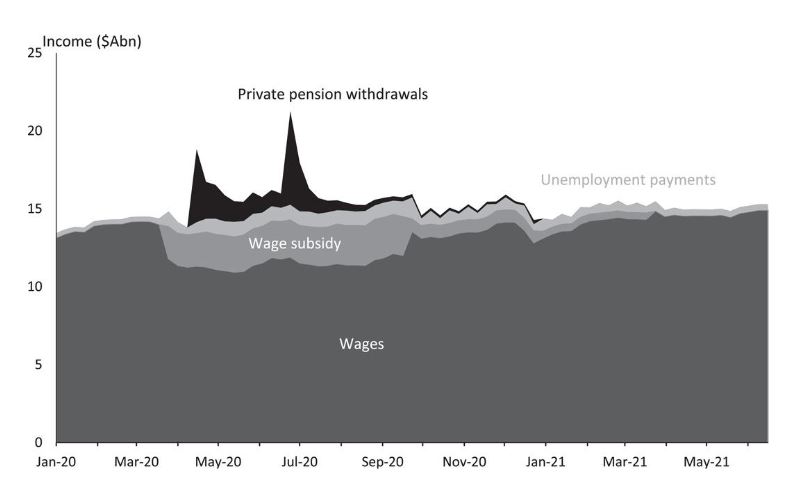

Fifth, the COVID-19 transfers (alongside resilience in earnings) served to increase total gross income flows among the adult Australian population in 2020. As represented in Figure 1, this is notable as income flows generally fall immediately after large adverse shocks.

Figure 1: Weekly income for the working age population

Policy implications

We expose important macroeconomic trade-offs that were implicit in Australia’s pandemic fiscal strategy.

At an aggregate level, transfers worth 9 per cent of annual GDP proved impossible to sustain over even the initial two-year phase of COVID-19. The first two waves of COVID-19 in 2020 saw strong protection of incomes. This protection was substantially weaker for subsequent waves in 2021 and 2022.

At an individual level, the unevenness of the pandemic response generated inequities. There were inconsistencies in the experience of the same Australians at different ‘waves’ of COVID-19. Transfers also treated Australians in similar positions differently.

The JobKeeper wage subsidy also represents a departure from the traditional approach of redistributing from those with a higher capacity to pay to those with lower capacities.

Our observations raise questions that can inform future crisis strategy.

Chiefly: is there a point where the level of cash transfer provided during a crisis becomes excessive, such that the costs of additional transfers outweigh the benefits? Or, to put it another way, when is there ‘too much of a good thing’?

Secondly, given the transitory and indeterminate nature of shocks, how comprehensive do transfers that are unveiled at the outset need to be? What role should contingent clawbacks and scale-ups, using real time data, play in crisis response? And how can decision-makers adapt for an Australian public discourse that seemingly expects large up-front announcements to assure confidence?

Those noted, we urge caution, when interpreting these observations, in making judgements around the suitability of pandemic policy.

Descriptive exercises like ours do not provide information about the ‘impact’ of policies and are limited to what they directly measure. They do not construct counterfactuals (the Australian economy would likely have looked very different in the absence of ameliorating measures) or identify mechanisms of effect. We are also reliant on indicators that reveal direct, rather than indirect, income consequences. We do not measure indirect macroeconomic effects of confidence-assuring action.

Where to now?

Our research provides insights about the intended and unintended effects of stimulus policy through cash transfers in response to crises.

A stronger, principles-based approach around the ways governments restrict people’s economic engagement in response to external events and their links with compensatory cash transfers, is desirable.

In addition, while it is impossible to know how long a crisis event will last at the onset of a crisis (and at the point when initial crisis measures are being enacted), a better alignment between the best available estimates of shock duration and the profile of fiscal and monetary support offers a welfare-improving prospect.

This should ideally include an explicit and publicly communicated strategy that accounts for contingencies in the event the crisis is prolonged or becomes more severe; and that ensures that emergency transfers are able to be delivered on a consistent basis across the entire expected duration of shock.

Related issues that warrant attention include: addressing a seeming public expectation that large, upfront spending commitments accompany every modern shock; and designing state-specific crisis policy tools such as clawback mechanisms for instances when such announcements are made but not appropriate.

We remain at the very early stages of the process in absorbing the public policy lessons revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tristram Sainsbury contributed to this work as a Sir Roland Wilson PhD Scholar in the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute.

Recent Comments