The Commonwealth Government levies specific taxes on tobacco products and alcoholic beverages because their consumption and abuse causes social harm. Often termed ‘sin’ taxes, they are used to increase prices and reduce demand. These taxes are very useful fiscal consolidation tools as higher tax rates on tobacco and alcohol products can increase revenue relatively quickly. Also, government spending pressures lessen to the extent that the higher prices reduce social harm.

The Commonwealth’s taxes on tobacco and alcohol products do not attempt to cover the full damage to society caused by their consumption and abuse. Such damage is very difficult to estimate accurately because it includes intangible social costs (for example, valuing impacts of trauma) and environmental costs as well as tangible social costs such as direct impacts on government expenses.

In contrast to the 1950s and 1960s, when federal governments were seen to take an even-handed approach to taxing tobacco and alcohol when horror budgets were announced, the picture is very different today. In 2016-17, the Commonwealth Government expects to raise $10.7 billion from specific taxes on tobacco products but only $6.2 billion from alcohol taxes. However, national accounts data collected since 1959-60 by the ABS (Cat no. 5204.0, 2016) indicate that household final consumption expenditure on alcoholic beverages, adjusted for changes in the price level over time, exceeded expenditure on tobacco products for the first time in 2015-16.

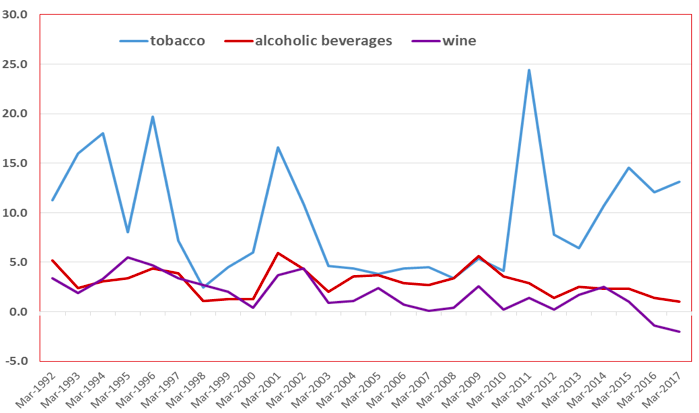

Furthermore, the 2017-18 Commonwealth Budget reveals:

- revenue from alcohol taxes is forecast to decline by 1.1 per cent in 2016-17, while revenue from tobacco taxes grows by 7.7 per cent;

- between 2016-17 and 2020-21:

- tobacco revenue is projected to increase by more than four times the rate of increase in alcohol revenue (see Table 1 below);

- as shares of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), tobacco taxation revenue is projected to rise by 20 per cent, whereas alcohol taxation revenue continues to decline slowly; and

- compared to estimates and projections published last December, alcohol taxation revenue was revised down by $660 million over the four years to 2019-20 while tobacco revenue was revised up by $340 million for the same period largely because of a measure designed to ensure that different tobacco products receive more consistent tax treatment.

Table 1: Commonwealth General Government Revenue from Specific Taxes on Tobacco and Alcohol Products

In other words, smokers are making a large contribution to fiscal consolidation whereas those consuming alcohol are not. What factors account for the apparent soft touch on alcohol taxation? There are many but four important interrelated causes are outlined below.

First, it reflects a legacy of past decisions that created a dual taxation regime for alcoholic beverages, and one so complex that governments have found it difficult to reform. The dual taxation system for alcohol dates from 1984 when the Hawke Labor Government applied a 10 per cent Wholesale Sales Tax (WST) to wine based on wholesale values, instead of bringing wine under the volume-based excise arrangements applying to beer and spirits. Nevertheless, prior to 1 July 2000, federal governments still had a price lever for wine – they could increase the WST rate.

Not so after 1 July 2000. The indirect tax reforms introduced then replaced the federal WST with the Goods and Services Tax (GST). At the time, there was a very good case for moving wine (as well as alcoholic cider, perry, mead and sake) into the volume-based excise arrangements. Producers were targeting the youth market with sugary alcoholic drinks and abuse of cheap cask wine was rife in many Indigenous communities, particularly in the Northern Territory. Surprisingly, this option was not advocated for wine in the A New Tax System (ANTS) reform document in 1998. Instead, the ANTS document announced that wine would be subject to a new ‘Wine Equalisation Tax’ (WET) to replace the difference between the 41 per cent WST and the proposed GST. A key intent was to preserve the concessional taxation treatment of the alcohol content of cask wine. The WET rate has been fixed in legislation at 29 per cent since 2000.

Because wine is still taxed on a value basis, wines with the same alcoholic content are subject to vastly different levels of taxation. The cheaper the wine, the less it is taxed, and the more it is consumed. In other words, the WET benefits producers of cheap cask wine relative to producers of premium wines. In 2015, the Parliamentary Budget Office published the following estimates of effective excise rates per litre of alcohol for wine, assuming all products were subject to excise:

- $2.99 for a $15 four litre cask of wine;

- $13.80 average for all wine; and

- $45.52 for a $40 bottle of premium wine.

Second, changing consumption trends – clearly influenced by the dual taxation regime ‒ are another factor. In 2015, the ABS (Cat. No. 4307.0.55.001), reported that over the fifty years to 2013-14:

- wine’s share of the total volume of pure alcohol consumed increased from 12 per cent to 38 per cent (and cider gained 2 per cent);

- beer’s share fell from 75 per cent to 41 per cent; and

- spirits, including ready‑to‑drink beverages, increased from 13 per cent of all pure alcohol consumed to 19 per cent.

These trends are important because, while wine and cider now comprise 40 per cent of apparent consumption of alcohol, the WET generates only 14 per cent of the total revenue from taxes on alcoholic beverages in 2016-17. They should also be of concern to policy makers as wine and spirits have a much higher alcohol content than beer.

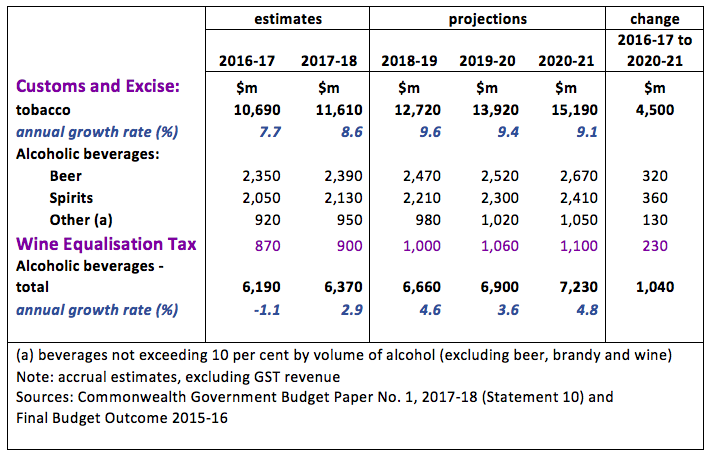

Third, without a uniform, volume-based government price lever supported by a floor price, and with the WET rate stuck at 29 per cent, governments can only lift the excise rates applying to particular beverages or all excise rates applying to beer, spirits and ready-to-drink beverages. There is little incentive for such changes because this would simply exacerbate the trend to greater consumption of wine. This lack of price leverage in the area of alcohol compared to tobacco, is reflected in changes in the relevant components of the Consumer Price Index over a long period of time (see Chart 1, below). Importantly, the wine component has fallen for the past two years.

Chart 1: Consumer Price Index: tobacco, all alcoholic beverages, and wine components (changes for years ending March, per cent)

Source: ABS Cat No. 6401.0, March 2017

Source: ABS Cat No. 6401.0, March 2017

Fourth, not reported in the Budget are estimates of the value of tax concessions for producers of alcoholic beverages. The largest tax concession benefitting producers that is reported in the Commonwealth Treasury’s Tax Expenditures Statement 2016 is the WET producer rebate, valued at $330 million in 2016-17 compared to WET tax revenue estimated at $870 million. The stated intent of the WET rebate is to benefit small wine producers in rural and regional Australia. Many wine producers rely heavily on this rebate and therefore changes to it are resisted.

The rebate cap is being reduced to $350,000 per year effective 1 July 2018 from the current $500,000, boosting WET revenue growth in 2018-19. This reduction is one year later than proposed in the 2016-17 Budget (see Megan Vine’s article for Budget Forum 2016), while the proposal to cut the rebate further to $290,000 has been abandoned. The 2016-17 Budget also included the $50 million Export and Regional Wine Support Package over four years to promote wine tourism at home and abroad. From 2019-20, a $10 million Wine Tourism and Cellar Door Grant program will provide grants of up to $100,000 to wine producers for their cellar door sales when they exceed their WET rebate. Government assistance programs over many decades, including the industry‑specific taxation arrangements, have attracted excess resources into the wine‑grape agricultural industry, such that exports of wine now constitute around 60 per cent of wine produced in Australia.

While Australia has been a world leader in actions to combat tobacco smoking, we lag most OECD countries in implementing policies to combat what is now a pervasive drinking culture. Not surprisingly, many in the wine industry, notably producers and exporters of premium wine, now agree that wine should be taxed under the excise arrangements. Certainly there is no public policy case for taxing wine and ‘traditionally-brewed’ cider, perry, mead and sake differently. As well as being an unnecessary, inefficient tax that favours cask wine producers, the WET is an industry assistance scheme, and a barrier to implementation of a consistent and coherent set of policies that can reduce the enormous social and environmental damage from alcohol marketing, consumption and abuse. Alcohol policy in Australia needs a total rethink, not more of the same.

Note: I acknowledge comments from Megan Vine.

In the UK alcohol is expensive and tobacco is ridiculously expensive. As a non-smoker I am all in favour, but it does lead to a lot of people making day trips to France and selling tobacco illegally !