In April 2015, Malaysia replaced the sales and service tax with a Goods and Services Tax (GST) to broaden the tax base and reduce the country’s heavy reliance on oil revenue, which made up more than 40 per cent of the federal government revenue in 2014. The aim was also to decrease Malaysia’s budget deficit, which had gone down from 7.4 per cent in 2010 to 3.2 per cent in 2015. With GST implementation, revenue collection increased by about 3 per cent to 219.7 billion Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) and reduced the fiscal deficit to 3 per cent of GDP in 2017.

Our study investigates how the introduction of the GST affected small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) owners in the retail sector. SMEs contributed 36.3 per cent to Malaysia’s economy (GDP) and employed 65.5 per cent of the country’s workforce in 2015.

Methodology

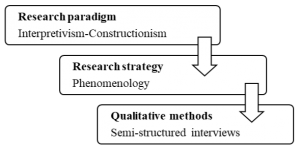

We follow a qualitative approach using the phenomenology research strategy, which report our findings to closely mirror the participants’ experience in the implementation of GST and their perception towards its introduction. The research framework for this study is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Framework for research

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with nine owners of GST-registered SMEs, within the framework of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). Except for one retailer, most businesses are well established with over 10 years of operations in various types of business, including fashion accessories, stationery, beauty products, education books, clothing, sundry goods and pharmaceutical products. Most of the businesses have been using computer systems in managing and controlling their operations prior to GST implementation, except for two traditional businesses that operated without using any IT system in any aspects of their businesses.

Developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen (1975), the Theory of Reasoned Action is a widely-used theory of social behaviour, frequently employed to analyse tax compliance. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship of its two components, attitudes (personal) and subjective norms (social influence), in predicting behavioural intention.

Figure 2: Theory of Reasoned Action

Attitude refers to a person’s belief and involves evaluation of certain implications resulting from a certain behaviour while subjective norms are perceived social pressure imposed on a person to take, or not to take an action. Hence, generally individuals will act on an action when they have positive evaluation on the action (to comply/ not to comply with tax), and when they believe that their social groups think they should take the action.

Using the TRA framework, we evaluate the motivating factor, or behavioural intention, that affects the actual behaviour of GST taxpayers. Positive compliance behaviours among taxpayers can be influenced by focusing on activities that improve the attitudes and subjective norms of the taxpayers.

Major findings

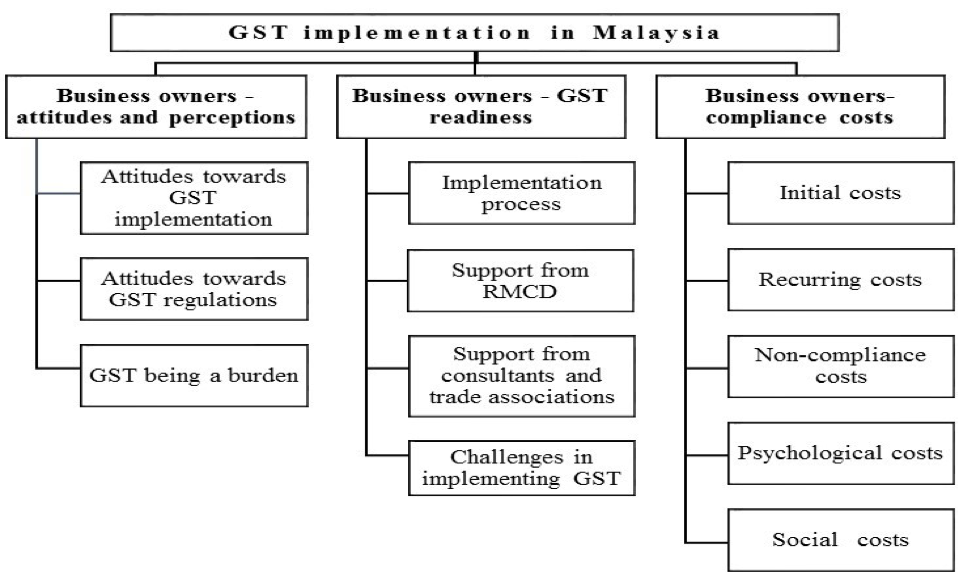

The participants’ lived experiences with GST implementation are classified into three main themes – business owners’ attitudes and perceptions, GST readiness and compliance costs – and 12 sub-themes. The sub-themes provide a richer understanding of the GST implementation experience among taxpayers, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Thematic map of GST implementation in Malaysia

Theme 1: Business owners-attitudes and perceptions

This theme explains the behavioural intention of GST taxpayers, which eventually leads to their actions. The attitudes and perceptions of business owners can be further described under three sub-themes: attitudes towards GST implementation; attitudes towards GST regulations; and perception of the GST being a burden. Generally, participants expressed negative views towards GST implementation and GST regulations, mainly due to increasing costs of doing business in Malaysia against a backdrop of an uncertain economic outlook and the depreciation of the Malaysian Ringgit.

The majority of the participants faced stress and anxiety from complying with burdensome compliance costs, including both tangible costs (initial, recurring and non-compliance costs) and hidden costs (psychological and social costs). The burden of compliance costs was exacerbated by a very short implementation period, and the increase in cash flow requirements to fund higher product costs, coupled with service costs and upfront payment of output tax to the Royal Malaysian Customs Department.

Theme 2: Business owner-GST readiness

Business owners’ GST readiness depends on several closely related factors, further analysed in four sub-themes: implementation process; support from the Customs Department; support from consultants and trade associations; and challenges in implementation. In this study, most of the participants were the primary drivers for their GST-readiness projects, which required significant investment of time and resources. Interestingly, one of the key successful factors in transitioning to the new tax regime is the support from family members, friends and fellow retailers.

In Malaysia, the Customs Department plays a crucial role in providing the necessary support, training and infrastructure on GST implementation. In this study, less than half of the participants claimed the e-voucher of MYR1000 offered to businesses for the purchase of software. Most of the participants incurred costs in attending privately-organized GST training or seminars, although complimentary GST workshops and trainings were offered by the Customs Department. There is also a significant expectation gap in terms of the delivery of necessary infrastructure to ease compliance, such as the usefulness of the official GST website and the GST Hotline by the Customs Department in addressing queries and concerns.

On the other hand, we noted significant involvement of IT consultants in supporting businesses in their GST implementation, while trade associations have shown little involvement in supporting and educating businesses, perhaps due to lack of interest from participants. In addition, the Customs Department appears to have collaborated with big trade associations and may not have reached various trade associations serving the needs of small business operators.

Some of the concerns raised by the participants include the diversion of existing resources to GST compliance matters, tighter cash flows, risks of unintentional errors or negligence committed by staff, and risks of inaccuracies in GST returns, caused by glitches in GST software.

Theme 3: Business owners-compliance costs

Compliance costs are elaborated under five sub-themes: initial costs (one-off investment); recurring costs; non-compliance costs; psychological costs; and social costs. Businesses need to incur considerable initial GST costs, including investment in IT software and hardware, GST-related training, hiring consultants (such as approved GST consultants, tax consultants and auditors) and other internal resources. The costs of compliance are fixed; hence they are regressive in nature with significant impact on small businesses, consistent with past compliance costs studies conducted in the United Kingdom, Netherlands, New Zealand, Germany and Canada.

The majority of the participants were anxious and worried (psychological costs) over the potential penalties arising from unintentional noncompliance with the Goods and Services Tax Act 2014, mainly due to errors by staff, lack of familiarity with the new GST system, and the degree of enforcement by the Customs Department. Some participants are not happy with the unfairness of overly strict non-compliance penalties (including jail terms), since they incur costs acting as GST collection agents for the government, without gaining any benefit in return.

We identify several stress-triggering factors among the participants, which may have an effect on their attitude towards, and perception of, the GST. Consequently, taxpayers may be influenced into perceiving the GST as an unfair tax forced on them, potentially leading to non-compliant behaviour. Finally, some participants voiced their concerns over the closure of small or traditional businesses, mainly due to their inability to manage the GST requirements, coupled with anxiety and fear (psychological costs) over the costs of non-compliance. This unexpected outcome of business closure is considered a social cost to the community, as it would cause inconvenience to the community in obtaining goods and services.

Conclusion

Our study provides a qualitative understanding of the various factors that influence the intention and compliance behaviour of GST taxpayers. The findings are useful to researchers, governments and policymakers in the design of long-term strategies to enhance taxpayer compliance behaviour.

In this case, the three main factors affecting the SME retail sector are the GST taxpayers’ perception of fairness, GST readiness of business, and external factors (such as economic development and currency fluctuation) affecting business operations.

In terms of subjective norms, namely social influences that affect taxpayers’ compliance behaviour, we find that peer-group influence (such as family members, friends and fellow retailers) play a major role in facilitating the transition to a new GST system.

Further Reading

Yong, MC, Kasipillai, J & Sarker, A 2017, ‘GST compliance and challenges for SMEs in Malaysia’, eJournal of Tax Research, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 457-489.

Recent Comments