Attracting inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational corporations has long been an important objective of many governments in developing and transition economies. In view of the perceived benefits of FDI and of its sensitivity to taxes, many such governments offer tax holidays and other tax incentives for multinational corporations.

The effectiveness of these measures depends in crucial respects on the tax regime prevailing in the multinational corporation’s home country (where the parent firm is headquartered). The benefit it receives from the tax holiday may be fully or partly undone by higher taxes owed to the home country. This is because the lower tax paid to the host country (where the multinational affiliates carry out business activity) lowers not only the local affiliate’s tax liability, but also the tax credit available to the parent in its home jurisdiction for taxes paid abroad.

As multinational corporations care about their combined tax liability to both governments, the developing country’s aim of attracting more FDI will be frustrated, as a tax incentive would only benefit the treasury of the home country, without benefiting the multinational corporation.

Tax sparing agreements

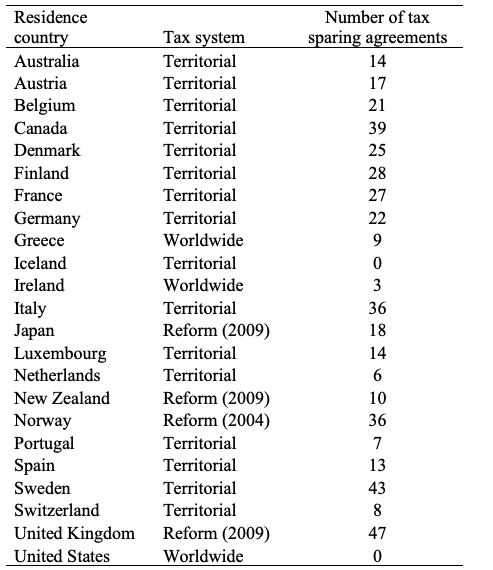

This fundamental problem has been discussed extensively since the 1950s, when the Royal Commission on the Taxation of Profits and Income recommended that the United Kingdom (UK) offer tax relief to its resident firms through its tax treaties in circumstances such as these. Since then, the UK, Japan and many other countries – with the notable exception of the United States – have developed an extensive network of tax sparing agreements, primarily with developing host countries (as documented in Table 1 below).

Tax sparing agreements are provisions that form part of bilateral tax treaties. They provide, in essence, that the home country agrees to provide its resident multinational corporations with a tax credit for taxes that would ordinarily have been due to the host country, but that are foregone (or ‘spared’) by the host country pursuant to a programme of tax incentives. This ensures that the host country’s attempts to provide tax incentives for FDI are not undone by the home country’s tax system.

Table 1. Tax system and tax sparing in the OECD in 2012

Note: ‘Reform’ corresponds to a tax reform from a worldwide tax system to a territorial tax system.

A controversial topic

Tax sparing provisions are arguably part of the foreign aid policy of developed countries and are designed to promote economic development.

From the perspective of developing countries, tax sparing is argued to represent an important tool accompanying their tax incentive programs, as it would be more difficult to attract foreign investment without tax incentives that can be protected via tax sparing. Other important arguments put forward by developing countries are that tax sparing allows them to target tax incentives to specific sectors of the economy and to exert greater control over their development programme.

However, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) called in 1998 for a reconsideration of tax sparing provisions in bilateral tax treaties, claiming that: ‘Investment decisions taken by international investors resident in credit [worldwide] countries are rarely dependent on or even influenced by the existence or absence of tax sparing provisions in treaties’.

Effects of tax sparing provisions on FDI

In a recent paper, we analyse the effects of tax sparing agreements on FDI using a large panel dataset on bilateral FDI from OECD countries. The data consists of stocks of FDI from 23 OECD-member home countries to 113 developing and transition host countries over the period 2002-2012. We code tax sparing agreements by searching the text of all existing bilateral tax treaties for language specifying a tax sparing provision.

We find that tax sparing agreements are associated with up to 97 per cent higher FDI. The estimated effect is concentrated in the year following the entry into force of tax sparing agreements, with no effects in prior years, and is thus consistent with a causal interpretation (that is, that tax sparing agreements cause higher FDI but not vice versa). This result supports the view that tax sparing provisions in bilateral tax treaties can be an important tool to encourage FDI in developing countries.

On average, OECD countries include a tax sparing provision in 31 per cent of their bilateral tax treaties with developing countries. Thus, it is feasible to disentangle the general effect of the treaties from the specific impact of tax sparing. Interestingly, we find that in the absence of tax sparing, bilateral tax treaties are not associated with significant increases in FDI, while treaties with tax sparing do have a large positive effect.

We also decompose the effects of tax sparing on FDI by investigating their effects on the extensive margin of FDI (the number of country pairs for which FDI starts due to tax sparing), and the intensive margin of FDI (the extent to which tax sparing increases FDI between country pairs with already established multinational firms). We find that tax sparing has an impact on the intensive margin by increasing FDI from already established firms, but it does not significantly affect the location of new multinational affiliates.

Worldwide system versus territorial system

The effect of tax sparing agreements might be expected to differ across FDI from home countries that have worldwide, compared to territorial (or exemption), tax systems. This is because those countries do not tax income earned abroad in the same way.

In the terminology of international taxation, the income generated by normal business operations in the FDI host country is referred to as ‘active’ business income, whereas other income (such as interest and royalties) is referred to as ‘passive’ income.

Home countries with worldwide tax systems impose tax on the active foreign business income of resident multinational corporations and generally give a credit for taxes paid to the host country. In contrast, home countries with territorial systems exempt the ‘active’ foreign business income of their multinational corporations from home country taxation. This income is only taxed by the host country. However, both worldwide and territorial home countries typically tax the passive foreign income earned by their resident multinationals.

We find no significant difference across worldwide and territorial home countries in the estimated effect of tax sparing on FDI. While this may appear surprising, it is consistent with a scenario in which the ability of worldwide multinational corporations to defer the payment (‘repatriation’) of dividends out of active income from their foreign affiliates to their parent substantially mitigates the burden of home country taxation. In such a scenario, the value of tax sparing for multinationals with worldwide home countries may not be much greater than the value of tax sparing for multinationals with territorial home countries.

This result suggests that much of the benefit from tax sparing is also available to territorial multinationals. This interpretation is supported by an additional finding that withholding tax rates on interest and royalties are strong determinants of FDI, especially when we consider global effective withholding tax rates adjusted for tax sparing provisions. This reinforces the continuing relevance of tax sparing in a world in which most home countries are territorial.

Further reading: Azémar, C & Dharmapala, D 2019, ‘Tax sparing agreements, territorial tax reforms, and foreign direct investment’, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 169, pp. 89-108.

Recent Comments