The Senate inquiry into Corporate Tax Avoidance has recently held hearings in relation to Australia’s offshore oil and gas industry and Monday 3 July 2017 was the second of three hearings on this topic. The Senate inquiry was extended late last year to include a consideration of the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT) for offshore oil and gas, and was the response by the Australian Labor Party and Australian Greens to the Turnbull Government’s announcement of a review into the PRRT. I have been researching for some time into the history and operation of Australia’s Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT) and subsequently made a submission to the Senate Inquiry. I was asked to appear at that Monday’s hearing as an expert witness and explain my perspective (watch video here). The senators conducting that hearing were Jane Hume (Lib., Acting Chair), Sam Dastyari (ALP), Senator Jenny McAllister (ALP) and Senator Peter Whish-Wilson (Greens).

Other witnesses on the day included Michael Callaghan, Chair of the PRRT Review; the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association (APPEA); the community groups, Tax Justice Network and Publish What You Pay; Santos, the Australian Taxation Office and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. The mix of witnesses and points of view promoted some Senators to ask: ‘If Australia is poised to become the world’s largest exporter of gas, then why are there domestic gas shortages – and at higher prices than those to export customers?’; ‘Is industry arguing that PRRT concessions should stay in place to provide the incentive to extract more gas to satisfy domestic market demand?’

A key point that I made before the Senate Inquiry was how the PRRT Regulations allow the gross undervaluing of the gas transfer price of the PRRT, to the detriment of tax collections and the community as owners of petroleum resources, which is consistent to my previous commentary on the shortcomings in the gas transfer price method prescribed by the PPRT Regulations. Indeed, the Callaghan “Final PRRT Final Report”, acknowledges the flaws of the PRRT gas transfer price method.

Australia has welcomed new business investment of $200 billion for integrated gas projects. However, lower than expected tax receipts have tempered the early optimism of gas project benefits to the wider community. In particular, petroleum resource rent tax (PRRT) revenues since the 2002-3 financial year have fallen. These reduced tax revenues have raised concerns about the effectiveness of petroleum taxation in Australia.

The basis of my Senate submission was my recently published research article (Kraal 2017) that examined the modifications necessary to the petroleum fiscal regime to address one of the PRRT Review’s aims of providing an equitable return to the Australian community. Findings from my article’s case study of Chevron-operated Gorgon gas project underpin my recommendations for PRRT specifically for integrated gas projects in Commonwealth waters.

My research is significant for its unique overview of Australia’s petroleum taxation since the fall in oil prices from mid-2014 and the rise of gas export projects. It calls for changes to the PRRT legislation as well as more uniform legislation for the taxation of petroleum resource projects.

I made six recommendations in my submission to both the Senate Inquiry and the concurrent Turnbull Government review of the PRRT, chaired by Michael Callaghan.

My recommendations included a call for changes to:

- The method for gas transfer pricing;

- The PRRT uplift rates;

- The PRRT exploration transfer concessions; and

- The Order of PRRT deductions;

- A revision to gas transfer pricing; and

- A focus on integrated natural gas-to-liquids projects in Commonwealth waters.

These recommendations were taken up in the Callaghan Final PRRT Report.

My last recommendation called for a re-introduction of royalties for integrated natural gas-to-liquids projects in Commonwealth waters that are currently only subject to the PRRT. Unfortunately this recommendation was not taken up by the Callaghan, Final PRRT Report. Nonetheless, there is a groundswell of public opinion still questioning the rejection of a re-introduction of royalties.

In the balance of this article I will explain the problems with the residual price method (RPM) for gas transfer pricing prescribed in the PRRT Regulation 2015.

How millions are lost in tax revenue from integrated LNG projects that use the residual price method (RPM) for gas transfer pricing

The questions and answers below highlight the issues with the rise of LNG projects in Australia and the legislative responses.

What is different about LNG projects in Australia?

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects in Australia are integrated, which means companies form a joint venture to operate activities upstream (extraction of gas at the field’s wellhead, and ‘cleaning’ of the gas at the conditioning plant to produce gas feedstock); as well as activities downstream (piping the gas feedstock to the liquefaction plant, converting it to liquid, and finally loading the LNG onto tanker ships for export).

Why are integrated LNG projects an issue for PRRT revenue?

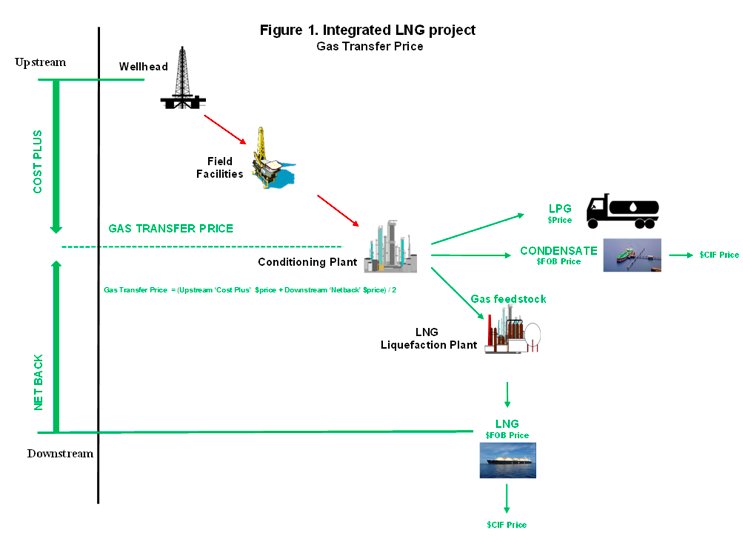

The Government’s PRRT revenue is calculated at a location called the ‘taxing point’ that is situated just before the gas feedstock (which is referred to as ‘sales gas’ in the PRRTA Act 1987) goes into the liquefaction plant (see Figure 1). The calculation for PRRT revenue is: gas price x volume x 40% PRRT rate (eg. price $10 x volume of gas sold 1,000 mcf x PRRT rate 40% = $4,000).

However, there is no “arm’s length” or fair market price for the gas feedstock used in integrated gas projects in Australia. This is because both the upstream and downstream operations in a gas project are typically conducted by a joint venture group of companies.

How do we deal with the problem of no arm’s length gas price?

Where there is no “arm’s length” or fair market price for gas in integrated LNG projects, PRRT regulations provide a method for calculating a ‘gas transfer price’ for the gas feedstock used in the liquefaction process. The method is referred to as the residual price method or RPM. Taxpayers, such as Chevron, are required to use this method if there is no comparable uncontrolled price (CUP), or Advance Pricing Arrangement with the Tax Office.

The RPM is a central design feature of the PRRT used to calculate PRRT revenues (from which exploration, capital costs and operating expenditures are deducted). The higher the ‘gas transfer price’, the more PRRT revenues for the Government, and vice versa.

How does the PRRT Regulation’s RPM method work?

The RPM is a combination of both the ‘Net Back’ and ‘Cost Plus’ pricing methods. This results in two different prices. The difference is divided by two. The RPM method seeks to establish the mid-point gas price between the upstream and downstream operations of an integrated gas project.

Figure 1 illustrates the RPM calculation requirements of the PRRT Regulations:

(i) Downstream: uses the Net Back method to determine a gas price. A price is calculated by taking the LNG sales price and multiplying by gas volumes, less downstream costs that include the liquefaction plant. The net result is divided by gas volumes.

(ii) Upstream: uses the cost plus method to determine a gas price. A price is calculated by adding all upstream costs from the wellhead to the boundary of the liquefaction plant, and dividing by gas volumes.

(iii) The final step is to add together the calculated gas prices from upstream and downstream, and divide by two to derive the ‘gas transfer price’.

What are the flaws in the PRRT Regulations’ RPM method?

The RPM’s combination of ‘Net Back’ and ‘Cost Plus’ pricing methods, as prescribed by the PRRT Regulations, is problematic for many reasons, many of which were identified in the Callaghan “PRRT Review Final Report”. In this single example, the ‘Cost Plus’ method used to derive the upstream gas price, only calculates costs from the gas field’s wellhead to the boundary of the liquefaction plant. It ignores the petroleum reservoir value, that is, it assumes the value of the gas reserves are zero. The resource is free of charge. There is no imputed royalty or PRRT cost. In other words, the upstream price is undervalued.

When the upstream ‘Cost Plus’ gas price is compared to the downstream ‘Net Back’ gas price, there will always be a difference. The upstream ‘Cost Plus’ price will nearly always be less than the downstream ‘Net Back’ price. The ‘gas transfer price’ is further reduced by the averaging process. A lower ‘gas transfer price’ results in lower PRRT revenues for the Government.

The RPM method clearly disadvantages the Government and the wider Australian community as the owners of gas resources. The flaws in the RPM method result in the Australian government losing millions of dollars in tax.

No other country in the world uses this ‘bespoke’ and flawed RPM method to determine a gas transfer price.

The RPM method is not used in the calculation of North West Shelf gas royalties, or for calculating the Queensland’s state royalty on onshore coal seam gas.

Neither the Tax Office nor the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (DIIS) in their testimonies on Monday 3 July 2017, could explain the RPM method for gas transfer pricing. The DIIS stated that in the early 2000s when the GTP was designed ‘it was a compromise with industry due to gaps in the data.’

What is the solution?

The current RPM method in the PRRT Regulations needs to be replaced. The ‘net back’ method is the alternative option for gas transfer pricing.

Reference

Diane Kraal (2017), ‘Review of the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax: Implications from a case study of the Gorgon gas project’, Federal Law Review, Vol. 45, Number 2, pp. 315-349.

Recent Comments