This is the second part of a two part series about the PepsiCo case, currently reserved for decision by the High Court of Australia, and what it may say about the efficacy of the general anti-avoidance rule in Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936).

Part I explained the key issues in PepsiCo. This part, Part II, details how Part IVA works, including why it was introduced and why, in 2013, the then government considered remedial amendments were necessary.

Why was Part IVA introduced?

Part IVA was introduced in 1981 to replace the anti-avoidance rule in section 260 of the ITAA 1936. Section 260 had been undermined by High Court rulings, tax avoidance had become rampant, and the burden of income tax was falling inequitably across the community.

Under section 260, arrangements entered for the purpose or effect of altering, directly or indirectly, the incidence of income tax were void for tax purposes. However, the High Court ruled that section 260 did not prevent taxpayers from choosing to artificially structure their arrangements to avoid tax that would otherwise have been due if they had transacted using more conventional legal forms (the choice principle).

Furthermore, the High Court held that the Commissioner of Taxation was not permitted to reconstruct transactions to create taxable situations in place of voided arrangements. In short, there was no taxation based on “economic equivalence”.

Part IVA was intended to address both limitations.

Firstly, Part IVA is based on an idea articulated by the Privy Council in its 1958 decision in Newton’s case. The Privy Council said that the overt steps by which an arrangement is implemented — that is, its legal form — may evince an objective purpose of avoiding tax on the end results achieved by the arrangement.

In other words, Part IVA is concerned with arrangements that, viewed objectively, are structured in blatant, artificial or contrived ways to take advantage of the way taxation laws attach tax consequences to changes in proprietary rights and/or legal obligations, rather than to economic outcomes.

Secondly, Part IVA empowers the Commissioner of Taxation to cancel tax advantages obtained from such contrivances; specifically, the non-inclusion of amounts in assessable income or the obtaining of allowable deductions (the avoidance of royalty withholding tax and other tax advantages were added to Part IVA post introduction).

In 1981, it was envisaged that this power would enable the Commissioner of Taxation to reconstruct “taxable” situations out of impugned arrangements. However, as discussed below, the Commissioner’s reconstruction powers have proved problematic, leading to the remedial amendments in 2013.

How does Part IVA work?

As mentioned in Part 1, the Commissioner of Taxation may cancel a tax benefit obtained in connection with a scheme if a participant in the scheme had a sole or dominant purpose of a taxpayer obtaining a tax benefit. Or, in the case of the Diverted Profits Tax, a principal purpose of a relevant taxpayer obtaining a tax benefit, or both a tax benefit and a reduction in foreign tax liabilities.

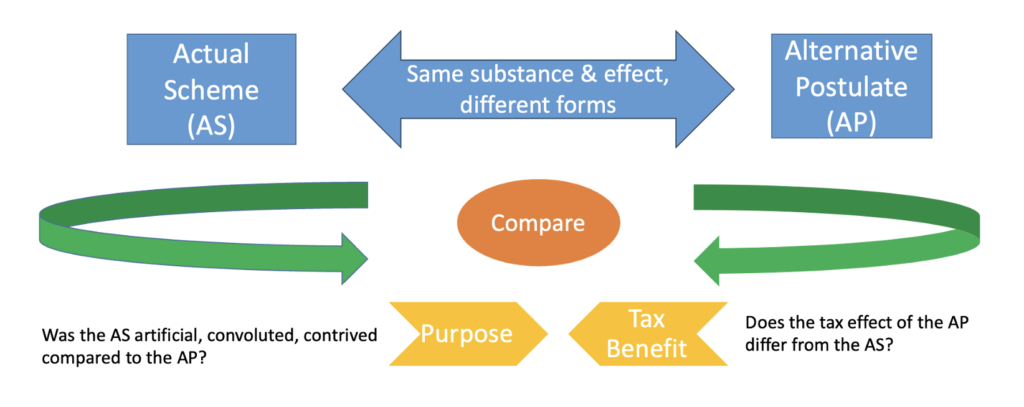

The statutory scheme revolves around three key concepts: scheme (it may be a single step or a series of steps), purpose (ascertained objectively considering the scheme’s form and substance, the manner in which it was implemented, its tax and non-tax consequences, its timing and the nature of the participants’ relationships) and tax benefit (specific kinds of tax effects). The concepts operate together, in an “interrelated” way, unified by an alternative postulate.

An alternative postulate is a hypothetical alternative to the actual scheme. The postulate may be simply that the scheme did not happen (an annihilation postulate). Otherwise, it must be a functional substitute for the scheme, being another way the taxpayer could reasonably have achieved materially the same substance and effect as the scheme, tax aside (a reconstruction postulate).

A comparison between the tax effect of the scheme and the tax effect of the alternative postulate(s) provides a means of identifying and quantifying the tax benefit obtained by the taxpayer. It also facilitates the purpose inquiry by demonstrating objectively, whether there were other less artificial or contrived ways the taxpayer could have achieved the same non-tax outcomes. If there were, then it might be inferred that the scheme was structured to secure the tax benefit.

This process is illustrated in the figure below.

In practice, the tax purposes of a scheme that generates allowable deductions, unmatched by real economic outlays, would be illuminated by an annihilation postulate. If the scheme did not happen, there would be no tax deductions.

But an annihilation postulate would not be effective against schemes which alter the incidence or character of an economic outlay, or economic gain. An annihilation hypothesis, though permissible under the statutory scheme, would not only expunge the tax mischief, but also the underlying economic and commercial activity.

In cases of that kind, the purpose and tax benefit inquiries would be best served by comparing the actual scheme to reconstruction postulates; namely, other more straightforward ways, in which the economic or commercial activity might reasonably have been pursued, and taxed.

Why was Part IVA amended in 2013?

By 2013, the Commissioner of Taxation had succeeded on Part IVA, in the High Court, in Spotless, Consolidated Press and Hart. In finding for the Commissioner, the High Court favoured a purposive construction of Part IVA which allowed the concepts of “scheme”, “purpose” and “tax benefit” to operate harmoniously, in the interrelated way depicted in the figure above. But the Commissioner’s success in the Federal Court was patchier.

Some Federal Court judges decided that, to determine whether a taxpayer had obtained a tax benefit, they must undertake a forensic examination into what the taxpayer would have or might reasonably be expected to have done if they hadn’t entered the scheme (see, for example, RCI, Axa Asia, Futuris and Trail Bros). These judges did not envisage that the Commissioner of Taxation could simply hypothesise the absence of the scheme, or a functional substitute for the scheme. This led them to compare the tax effect of actual schemes with the tax effect of counterfactuals which bore no economic or commercial equivalence to the actual schemes.

This was contrary to the internal logic on which Part IVA is predicated; that is, that the tax avoided is the tax that would have been payable on the end results of the arrangement (if any), had it been implemented in a more conventional legal form.

Perversely, from a tax policy perspective, the Federal Court’s approach meant that taxpayers who participated in highly artificial schemes did not obtain tax benefits to which Part IVA applied if they could point to evidence that, but for the schemes, they would have avoided doing anything that would have exposed them to more tax. In effect, the tax avoided by the schemes became the very feature which protected the taxpayers from the application of Part IVA.

This is why the remedial amendments were enacted in 2013. The then government thought Part IVA would be frustrated if the Federal Court reasoning became entrenched. It therefore sought to make explicit what the High Court, in Spotless, Consolidated Press, and Hart, had taken to be implicit: namely, that

- “purpose” and “tax benefit” are interrelated;

- “tax benefits” and “purpose” are demonstrated by comparing actual schemes to hypothetical alternatives;

- hypothetical alternatives may be annihilation postulates and/or reconstruction postulates; and,

- reconstruction postulates must be functional substitutes for actual schemes, disregarding tax.

The government said it did not intend a change in policy and minimised the scope of the amendments to preserve existing High Court jurisprudence on Part IVA.

In what sense are the remedial amendments at issue in PepsiCo?

As explained in Part I, a plurality in the Full Federal Court concluded that the foreign members of the PepsiCo group did not obtain any tax benefits because there was no dissonance between the commercial and economic substance of the group’s arrangements with Schweppes Australia, and the legal form of those arrangements.

However, the judges also characterised the process for identifying reconstruction postulates as evidence-based exercises in prediction (see [95]—[97]). This is more troubling from a policy perspective. It mirrors submissions put by PepsiCo (see [48]—[51]), citing now outdated reasoning in Peabody that reconstruction postulates must be “reliable predictions” rather than “mere possibilities”. It also mirrors recent dicta in Ierna and Guardian AIT.

This is to impose on reconstruction postulates the pre-2013 notion that “tax benefits” must be established by inference from foundational evidence as to what might reasonably be expected to have happened but for a scheme. It conceives of “tax benefit” as a “gateway test”.

But such a notion defies the internal logic of Part IVA (depicted above) wherein alternative postulates are components of holistic inquiries into whether schemes were carried out in particular ways to achieve particular tax effects. These are objective evaluations of what was actually done by reference to what could have been done (or not done). A threshold requirement that reconstruction postulates (but not annihilation postulates) must be “reliable predictions” does not aid that inquiry. The place for testing the plausibility of alternative postulates is in the holistic inquiry.

Where to next?

It will be interesting to see what the High Court makes of the changes to Part IVA should they consider it. If it concludes that the 2013 amendments were not effective to oust the old Federal Court approach to tax benefits, and/or that the amendments do not operate harmoniously with the other provisions of Part IVA, the efficacy of Part IVA is likely to be undermined, compelling future governments to revisit the design of Part IVA.

Disclaimer: Kate Roff contributed to the design of the 2013 remedial amendments in her then position as a Principal Advisor in the Commonwealth Treasury. The views and opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and are based on the author’s own understanding of the statutory provisions.

Recent Comments