“Are other taxpayers paying their fair share, or am I the only one?” Answers to questions like these are crucially important for own subsequent compliance behaviour. Especially businesses that do not pay the correct amount of tax contribute to creating distrust in the effectiveness and fairness of the tax system due to their exposed position when fraud is detected. Outstanding tax debts affect the ability of governments to finance public services. This can have severe long-term consequences if taxpayers perceive non-compliance as socially acceptable. That is why tax collecting bodies are increasingly looking for ways to complement traditional deterrence approaches with new interventions inspired by behavioural insights.

Business taxation in Australia

Australian businesses owe more money to the tax office than individual taxpayers. They also have more opportunities to evade payment or to underreport because they are less often subject to tax deductions at the source of their payment or to third-party reporting. As a consequence, only a fraction of business tax non-compliance is detected.

Collectable debt in Australia has increased from $14.7 billion to $19.2 billion in the 2014-15 financial year. Although the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is considered one of the most efficient tax collecting bodies in the world, it writes off more than 20% of outstanding debt. Businesses are responsible for a large part of that. Due to their substantial contribution to government revenue and the higher probability to engage in tax avoiding activities, they constitute a highly relevant target group for interventions that aim to increase voluntary tax compliance.

Behavioural insights and the ATO

In cooperation with the ATO, researchers from the Australian National University (ANU) are currently making use of behavioural insights to evaluate the effects of certain interventions on tax compliance. Newly published results from two trials targeting business taxpayers provide some interesting insights into this under-researched field.

The key result in a nutshell: Businesses can be nudged towards tax compliance but it is the nature of the nudge that is important.

Both studies were conducted as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) satisfying the criteria of a natural field experiment. In other words: The trials were designed to preserve realism in all relevant domains, for instance the treatment of the experiment closely approximated the types of interventions that are likely to occur in the real world and the outcome measures resembled the outcomes that are of practical interest.

RCTs offer great advantages. Allocating an intervention to a randomly chosen group of business taxpayers while withholding it from another enables researchers to identify the causal effect of this intervention by simply measuring differences in outcomes (and potentially controlling for differences in group-characteristics, if there are any). Moreover, testing several interventions at the same time provides systematic evidence on the effectiveness of a range of interventions. This permits inferences about policies that are likely to work in similar contexts and makes the results highly relevant to researchers and policymakers alike.

Trial I: Revising business activity statements

The first trial focused on businesses paying the correct amount of tax. If transactions vary considerably from normal business activity, businesses may receive a personalised letter from the ATO asking them to review their business activity statement (BAS) and to notify the ATO if an error occurred.

The aim of the trial was to test the effect of changes to this letter on response rates of taxpayers, the timing of payments, and the amount of payments of liabilities. Four interventions were tested: (1) Timing: Extending the due date by two weeks, (2) Social Norms: Changing the heading of the letter from “You need to review your GST refund claim” to “Our tax system works because people do the right thing”, (3) Colour: Changing the colour of heading and subheading from blue to orange to induce a feeling of urgency, and (4) Warm Glow: Informing taxpayers about tax deductible donations to appeal to their social conscience. Each intervention involved a single change in letter content or style.

The results of the trial are sobering in a way: None of the four treatments had a significant effect on any of the outcome variables considered. Several factors may be responsible for this result.

First, the differences between treatment and control letters were rather small. For example, the control letter was almost identical to the letter in which the colour was changed in a few places. Even though research from other domains indicates that compliance is affected by apparently small details such as timing, framing, and visual presentation, the tested nudges may have been too small to actually induce a behavioural change.

Second, the sample size (up to 589 observations in each treatment and control group) may have been too small to detect an effect.

Third, despite these limitations, it is possible that businesses are simply not very responsive to this type of intervention. While researchers have recently found significant effects of similar nudges on the behaviour of individual taxpayers, we still know very little about behavioural responses of businesses, which constitute a very different type of taxpayer.

Trial II: Compliance with employer obligations

The second trial studied compliance with employer obligations. Employers in Australia have to transfer money into different government funds to fulfil their tax and superannuation obligations. Field auditors and desk auditors of the ATO regularly conduct payment conversations with business taxpayers and send out a notice of audit to check compliance.

The trial consists of two parts. The first part assesses the effect of changing internal guidelines used by field auditors to raise awareness of the relevance of tax debt payments. The new guidelines emphasise the importance of payment conversations with taxpayers. The second part focuses on studying the effect of simplifying a letter and changing the phone script of desk auditors to offer taxpayers a direct connection to an ATO officer to work out a suitable payment plan. Study outcomes include debt collection measures, the duration of case cycles, and information about whether a default assessment was raised by the ATO during the audit (an indicator that taxpayers did not comply with their filing obligation).

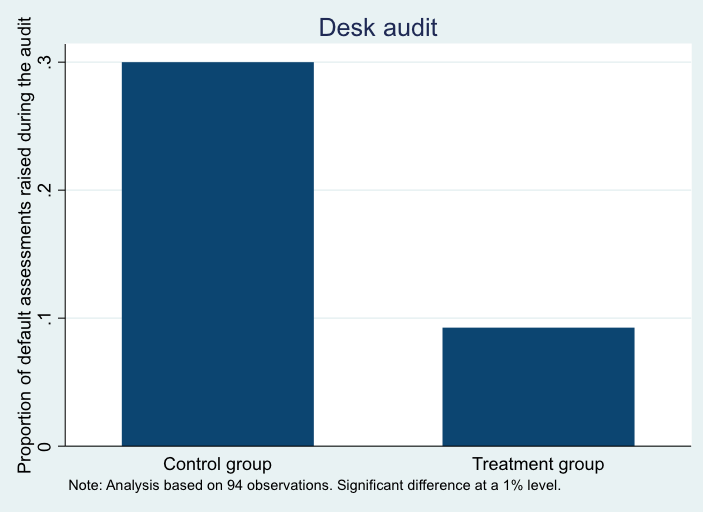

The results indicate that changing internal guidelines used by field auditors (first treatment) reduced the amount owed by the taxpayer at the end of the case cycle from $133,000 to $69,000. This effect disappeared when differences in observed characteristics between the treatment and the control group were added as control variables. In contrast, simplifying the letter and changing the phone script used by desk auditors (second treatment) reduced the proportion of default assessments raised by the ATO substantially (from 30% to 9.3%), and this effect remained significant even when control variables were added to the model (see figure below).

Taken together, the results suggest that the treatments led to some improvement, indicating that businesses are responsive to nudges like simplification and the provision of help with setting up an individualised payment schedule.

Lessons learnt

All in all, what can we learn from these two trials?

First, from a policy perspective, the findings suggest that clearly noticeable interventions are required when targeting businesses to induce behavioural change. While small changes to letters have been found to result in behavioural changes among individual taxpayers, the trial results provide first tentative evidence that businesses are less responsive to low-key nudges.

Second, the findings point to the most promising domains to improve voluntary business tax compliance. Businesses appear to act “more rationally” than individuals due to structural factors (businesses may have more than one person who is responsible for tax filing and may be less likely to be affected by the decision than individual taxpayers). Consequently, interventions that aim to reduce friction costs for businesses appear to be most promising when targeting compliance behaviour. The second trial shows that changing the phone script of desk auditors to help setting up a payment arrangement and simplifying the follow-up letter has a substantial effect on the filing behaviour of businesses. Therefore, tax authorities should identify areas in which barriers may prevent businesses from compliant behaviour, and apply behavioural insights in these areas.

Finally, we need more systematic business tax compliance research. Not understanding the broader implications of business tax non-compliance has severe societal and administrative costs. It is therefore highly commendable that tax administrators are increasingly open to running RCTs to evaluate the effects of policy changes on the real-world behaviour of taxpayers. Governments and institutional representatives alike should support this development to derive a sound base of empirical insights into the effectiveness of different approaches to increase voluntary tax compliance. It is in their own best interest.

Recent Comments