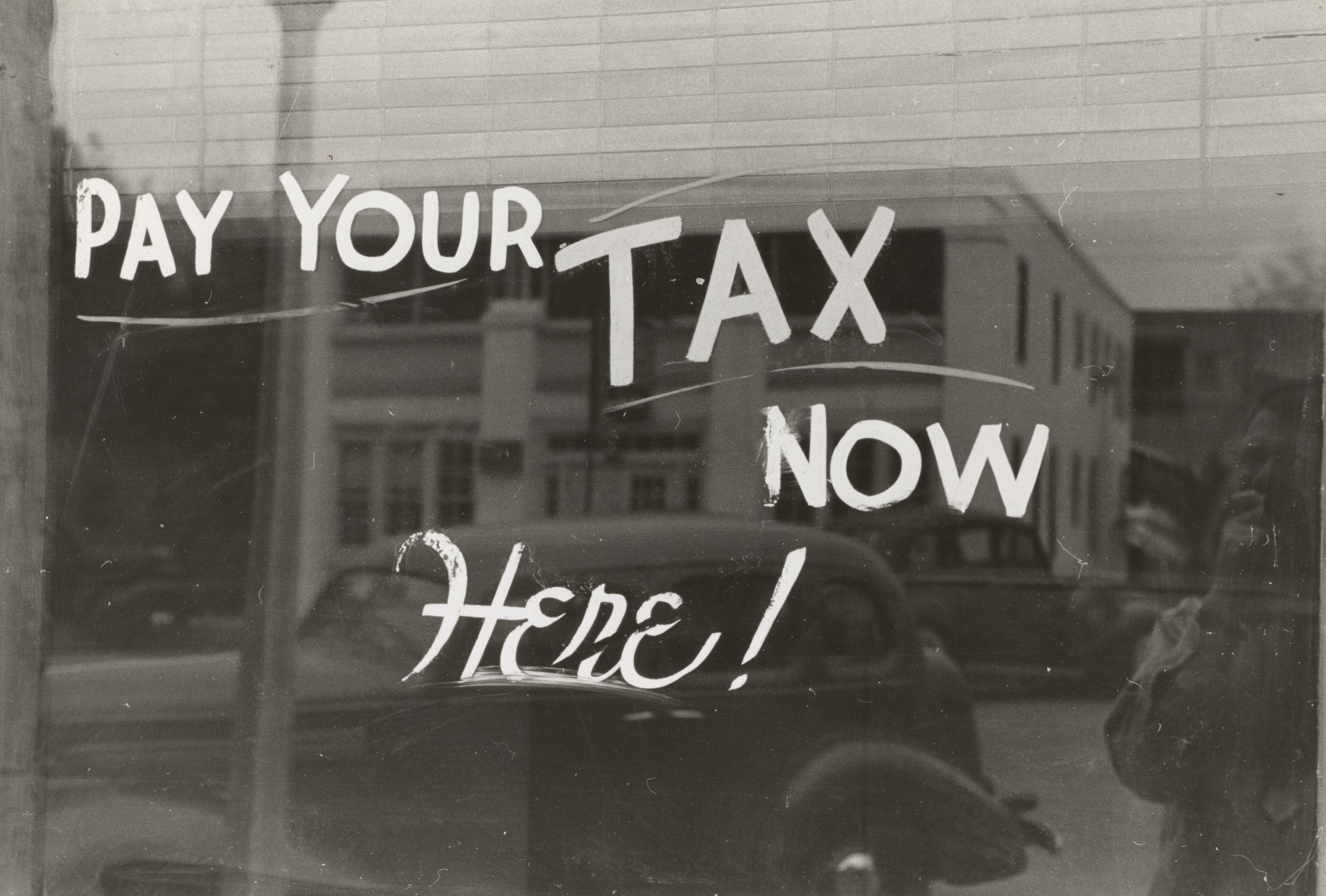

Policymakers are increasingly relying on behavioural interventions with the aim of improving individual decisions. These interventions have become known as ‘nudges’ following the similarly titled book written by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in 2008. Nudging methods are used, for example, to increase the willingness of individuals to pay taxes. But how effective are these measures in reality? Our recent review paper helps answer this question.

What is a nudge and in which policy areas have they already been applied?

Thaler and Sunstein (2008) define a nudge as ‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives’. One of the most common nudge interventions on behalf of the government entails sending notifications, such as letters or personal visits, from various government agencies.

Nudges have become extremely popular in the last decade across a number of policy areas. They have been used to contribute to healthier eating diets, improve children’s educational outcomes, reduce emissions, and encourage savings behaviour, among other policy goals. For instance, automatic enrolment in retirement savings plans can help younger people save more. Simple but targeted reminder letters sent by health authorities can increase the uptake of healthcare screening programs. Letting consumers know that they are spending more electricity than their neighbours can substantially change their consumption behaviour.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has counted over two hundred nudge units that have been set up by local, national and supra-national institutions across the world to design and implement behavioural interventions. Some of the most well-known units are the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), the World Bank’s Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD), or the White House’s Social and Behavioral Science Team (SBST), among others.

How do nudges work in the area of tax compliance?

Nudging practices have also become widespread in the area of tax compliance, a policy challenge that is relevant in almost all parts of the world. Tax compliance is not only relevant for ensuring efficient and fair taxation, but also for safeguarding appropriate levels of public goods provision.

The starting point behind these interventions is the presumption that taxpayers pay their taxes not only because of the fear that they will be punished for not doing so but also because taxpayers like to pay taxes voluntarily for moral reasons. Consequently, two general types of nudges – deterrence and non-deterrence ones – are designed that appeal to respectively the compulsory and voluntary reasons behind paying taxes.

More specifically, deterrence nudges are interventions that emphasise traditional determinants of compliance such as audit probabilities and penalty rates. Non-deterrence nudges, on the other hand, try to appeal to various moral aspects – such as saying that not paying tax is unfair and reduces the availability of public goods – and social norms – such as saying that almost everyone pays their tax on time – without any mention of threat that has the potential to alter the taxpayers’ financial motives.

Meta-analysis is a method of quantitatively reviewing the available body of evidence, how does it work more exactly?

In our paper, we present a quantitative review, a so called meta-analysis, of about a thousand treatment effect estimates of nudges obtained from around forty-five interventions. The nudging interventions of De Neve et al. (2019) in Belgium, Dwenger et al. (2016) in Germany or Hallsworth et al. (2017) in the UK are examples of some of the better known studies. The field is however much larger mainly covering countries of North and South America and Europe, and it is growing by day. Although, experiments from Africa are currently somewhat lacking, new studies – including an ongoing multi-country study, the Metaketa II – target these countries as well. For recent literature reviews, see Mascagni (2018) for a discussion of tax experiments, and Slemrod (2019) for a review of the more general literature on tax compliance.

Of course, these various experiments may arrive at somewhat different findings and the exact details of their experimental designs may be somewhat heterogeneous. Meta-analysis is a methodological tool allowing to bring the multiple treatment effects estimates of nudges coming from these various experiments together with the aim of arriving at a consensus estimate of the size of the effect as well as studying the reasons behind the heterogeneity in estimates. In this particular case, what is helpful is that the different studies are all randomised control trials operating within the same methodological framework, such that a comparison of estimates across experiments is a meaningful exercise.

What are the main findings?

The bottom line finding of the meta-analysis is that non-deterrence nudges – namely interventions pointing to elements of individual tax morale – are on average ineffective in curbing tax evasion once they are evaluated against a control group of taxpayers receiving neutral communication. While the study shows that deterrence nudges – namely interventions emphasising traditional determinants of compliance such as audit probabilities and penalty rates – are potent catalysts of compliance, the magnitudes of these effects are overall quite small. Deterrence nudges increase tax compliance at the extensive margin by only 1.5-2.5 percentage points compared to non-deterrence nudges.

Despite these modest baseline effects, additional findings of the meta-analysis highlight certain design aspects of experiments that may make them potentially more effective. For example, nudges communicated through in-person visits deliver more powerful results in terms of compliance outcomes than nudges communicated through letters. In terms of different groups of taxpayers, the practice of selecting to focus on previous non-compliers (such as late-payers) or on taxpayers in higher income countries can potentially increase the effectiveness of nudges.

On the other hand, an important finding is that the effects of nudges are likely to be bound to the short-run. Additionally, in line with DellaVigna and Linos (2020) and a long-standing debate in empirical economics on publication bias, this meta-analysis also shows evidence that these experimental estimates of already small magnitude are likely to be inflated by selective reporting of results.

Should policymakers abandon the use of nudges given your findings?

The implication of our review paper is that nudges do not revolutionise the world, certainly not the world of taxation. And so, the question is why nudges are so popular among policymakers.

One reason is the belief among both policymakers and academics that these notifications are virtually costless. This belief comes from equating the costs of nudges to the physical costs of sending the communications, such as the postal fee for sending an envelope, which are obviously negligible. If the costs are nearly zero, as the argument goes, than a positive effect on compliance of even a very small magnitude would still suggest that nudges are an infinitely cost-effective policy tool.

The trouble is that the costs of nudges are very likely to go well beyond the physical costs of sending communications. These costs are difficult to quantify, but they involve potentially substantial compliance costs that taxpayers face as well as credibility costs on the side of the tax authority. Allcott and Kessler (2019) show that the failure to take into account these costs will lead to a massive overstatement of the positive effects of nudges on social welfare.

In addition to the tendency to underestimate the costs of nudges, these interventions are often fairly easy for policymakers to understand, as opposed to having to dive into more sophisticated and lengthy research-based policy advice, which makes them so attractive especially in low capacity environment. What’s more, implementing nudges may serve as signal from politicians to voters that the government is relying on (behavioural) science to improve policy.

With that said, nudging policies may crowd-out efforts going into the design of traditional economic policy reforms. Reforms of taxes, subsidies, and other policy tools that aim to change behaviour by altering the underlying economic incentives. In this respect, there may be a risk of too much excitement among policymakers around the idea of nudges. Nudges are simply no substitutes for classical economic policy instruments.

Further reading

Antinyan, A. and Asatryan, Z., 2020. Nudging for tax compliance: A meta-analysis. CESifo Working Paper No. 8500.

Recent Comments