Policymakers and economists have long assumed that high-income individuals save most of a temporary increase in income. This belief has shaped fiscal policies, leading to stimulus payments that phase out at higher incomes and weaker social insurance protections for high earners. The idea is that wealthier individuals are more likely to save rather than spend temporary income boosts, making such policies less beneficial.

Our evidence challenges this assumption. Using Danish administrative tax data from 2000 to 2016, we estimate that taxpayers at the top tax bracket have an annual marginal propensity to consume (MPC) of 0.6. This means that when high-income earners receive a temporary income increase, they spend 60% of it over the course of a year rather than saving it. This is higher than standard economic models predict and has important implications for how fiscal stimulus and social insurance policies are designed.

If high earners are spending more than expected, excluding them from stimulus programs weakens the overall effectiveness of such policies. Similarly, if high earners experience large drops in consumption when their income falls, stronger social insurance protections may be needed. The assumption that high-income households can self-insure against income fluctuations may not hold as strongly as previously thought.

For policymakers designing tax rebates, unemployment benefits, or crisis-response measures, these findings suggest that income-based means testing should be reconsidered. While policymakers may still wish to target lower-income earners on equity grounds, our research shows that high-income earners should not be excluded because they have low spending propensities.

Estimating the MPC for high-income earners

Most previous studies on spending behaviour rely on lottery winnings, stimulus payments, or survey data, all of which provide valuable insights but come with limitations when trying to answer our specific question.

Lottery studies offer a clean and exogenous source of income variation—individuals do not anticipate winning, making it an excellent way to study how unexpected income changes affect spending. However, lottery winnings differ from regular income fluctuations because they are windfall gains. People may respond differently to lottery winnings than typical fluctuations in labour income because of framing or mental accounting effects.

Studies of fiscal stimulus payments provide important evidence on short-term consumption responses to temporary income increases. However, these payments are phased out for higher-income earners, leaving a gap in our understanding of how upper-middle-class individuals respond to transitory income shocks. Since the assumption behind this phaseout is that high earners save rather than spend stimulus payments, we lack direct empirical estimates to verify whether this is actually the case. Australian studies have also focused on non-durable rather than overall consumption.

Survey-based estimates, where individuals are asked how they would spend a hypothetical income increase, are widely used and allow researchers to measure self-perceived spending propensities. However, actual behaviour potentially differs from self-reported intentions, and responses can be influenced by recall bias, hypothetical framing, or difficulties in predicting one’s own behaviour in real economic situations.

Our study takes a different approach: we use Denmark’s tax system to measure real-world responses. The Regression Kink Design (RKD) allows us to estimate the MPC based on predictable changes in after-tax income at a sharp threshold in the tax system. However, one might ask: why hasn’t this approach been used before?

The RKD is a relatively new econometric method, and applying it effectively is extremely data demanding. It requires a very large number of observations to detect spending responses precisely. We solve this using the Danish full-population administrative registers available to researchers.

Another data challenge is that even in administrative data, consumption is typically not directly observed. However, thanks to the richness of Danish register data, we are able to impute consumption following previous research using Danish data. By leveraging information on income, wealth, and financial transactions, we construct a reliable measure of household consumption that allows us to estimate MPCs at a high level of precision.

Visual evidence: How consumption changes at the tax kink

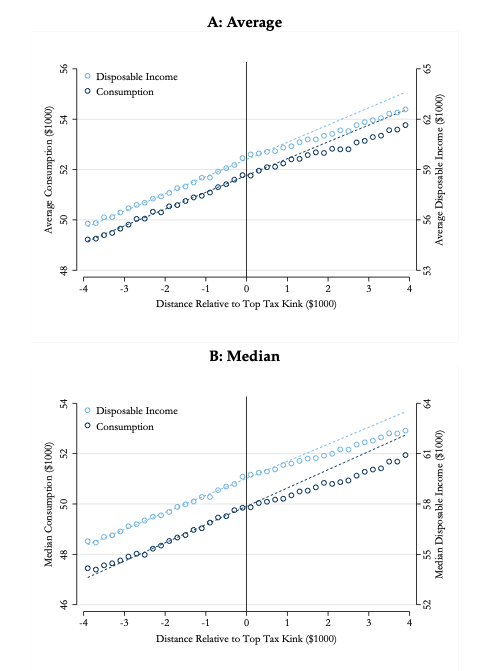

Figure 1 illustrates our methodology. The x-axis represents income levels around the top tax threshold, while the y-axis shows disposable income (light blue dots) and consumption (dark blue dots).

Figure 1: Evolution of disposable income and consumption around the top tax kink

To the left of the threshold, disposable income rises steadily with earned income. To the right of the threshold, the increase in disposable income slows due to the higher marginal tax rate. Consumption follows a similar pattern, with a noticeable drop in the rate at which spending rises above the tax threshold.

What we find: By comparing the slope change in consumption relative to the slope change in income in Figure 1, we estimate that high-income earners have an MPC of 0.6. The estimated MPC for taxpayers at the top tax bracket is 0.6, which is significantly higher than standard economic models predict.

Reliability of the estimate: To ensure our estimate is valid, we focus exclusively on wage earners, avoiding biases from self-employment income manipulation. We also show that individuals just below or above the threshold are not systematically below or above the threshold in future years, confirming that the income variation we exploit is predominantly temporary.

A concrete example: Consider a one-time DKK 10,000 tax rebate introduced to stimulate the economy during a downturn. Standard policy thinking would target only lower-income households, based on the assumption that high earners will not spend it. Our research suggests otherwise. If high-income earners were included, they would spend DKK 6,000 of the rebate, significantly boosting aggregate demand.

Policy implications: Rethinking fiscal and social insurance policies

Australian stimulus payments made during the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have been phased out at higher incomes, presumably under the assumption that wealthier individuals will not spend them. Our research suggests that including upper-middle-income earners in such programs could significantly boost consumer demand. If high earners spend 60% of a rebate, omitting them reduces the total increase in consumer spending, weakening the macroeconomic effects of fiscal stimulus.

Social insurance programs such as unemployment benefits and income support often provide less generous coverage to high earners under the assumption that they can self-insure against income shocks. Therefore, ensuring adequate income protections across the income distribution strengthens the automatic stabiliser effect of social insurance, mitigating broader economic downturns. Our findings indicate that high-income earners experience significant consumption drops when their income falls. This suggests that strengthening income protections for them could enhance the role of automatic stabilisers, ensuring a smoother adjustment of aggregate demand during economic downturns.

Recent Comments