Most people don’t like paying tax. Nor do people like paying more tax than they do currently. Recent global media attention has focused especially on companies’ behaviour, with accusations of multinationals effectively choosing where to pay their taxes and how much to pay—or avoiding tax altogether. But the issue is just as relevant for ordinary Australians and New Zealanders.

For example, someone in New Zealand currently earning $75,000 a year pays $15,670—or about 21 percent—in income tax. But for every dollar they earn over $70,000 ($5,000 in this case) they pay 33 cents in tax, taking home just 67c.

Now imagine this top tax rate is almost doubled to 60c in the dollar. If they keep earning $75,000, they will pay an extra $1,350 in tax, raising their average tax rate by less than two cents to 23 percent. But for every dollar earned over $70,000, this taxpayer now only gets to take home 40 cents.

Would you work extra overtime if you got to keep just 40 cents out of every dollar earned instead of 67 cents or more? If earning more also means losing transfer payments like family tax credits, you could end up with less than 40c per dollar.

High tax rates have another, more insidious, effect: some taxpayers go looking for ways to avoid the extra tax, either legally or illegally. Negatively gearing a rental property, or earning less income while your lower-paid partner earns more, are two of the legal ways. Or you might go and work in Hong Kong, where tax rates are lower.

Discovering these sorts of responses to higher taxes is the driving force behind a new research project being run by Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. The project will run over the next three years, supported by funding from the government’s Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Using the latest tax-transfer modelling techniques and data for New Zealand, the project will look at how people alter their behaviour when taxes change.

These behavioural impacts are important for several reasons.

Firstly, illegal tax avoidance undermines the tax system’s fairness and credibility by forcing law-abiding taxpayers to pay more. Secondly, all tax-avoiding responses involve lost revenue that otherwise could fund better public services or welfare benefits. Thirdly, such difficult-to-predict revenue losses make it harder for governments to forecast how much extra revenue they can expect from a new tax policy, and so how much more they can afford to spend. Fourthly, these responses also undermine the efficient running of our economy. If entrepreneurs and the self-employed spend their time on ways to minimise their taxes, this is time that could be better spent doing what they are good at, generating new ideas and employment along the way.

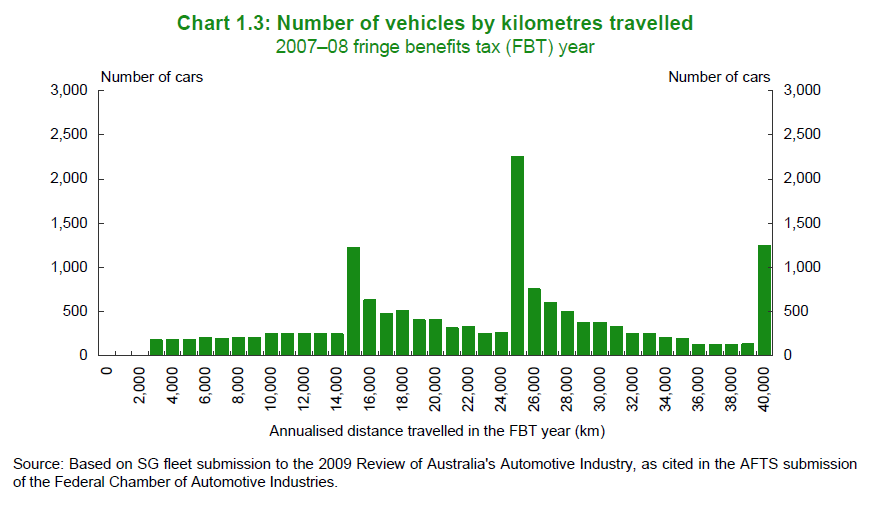

A good illustration of behavioural responses is the Australian Fringe Benefits Tax (FBT). For Australian employees who have a company-owned car, FBT is levied on any kilometres driven for personal use. Until recently, the tax rate per kilometre was lower (on all the personal use kilometres) if you travelled more than 15,000kms, then lower still if you travelled more than 25,000kms and more than 40,000kms. So, clearly, driving more—or claiming to—would be good for your FBT bill.

It is hard to know exactly how many kilometres Australians would have driven if there was no FBT regime. But data on how many cars travel various distances, collected for Treasury’s Henry Review of Taxation (2009), depicted in the graph above, showed an awful lot of Australians paying FBT reckoned they drove just over 15,000, 25,000 and 40,000 kilometres. Very few company cars travelled other distances. Strangely, that aligned remarkably well with their fiscal interest.

Tax researchers in other countries have identified many examples which are similar to this Australian case. But not a lot is known about New Zealand income taxpayers. Getting a better understanding of how Kiwis respond to their taxes, through the Victoria University tax-modelling project, could potentially help improve understanding of the New Zealand tax system and assist future tax policy setting. In this respect at least, Australian income tax modelling seems to be ahead of New Zealand with the Melbourne Institute already able to estimate behavioural responses in their ‘MITTS model’. Indeed, in New Zealand we hope to learn from their trail-blazing!

So, a first step towards a fairer and less distorting tax system in New Zealand has to be better knowledge of how distorting and equitable the current system is. This way, we might help Kiwi governments and voters make better choices over what kind of tax system they want. Hopefully Australian tax policy-makers considering reforms to Australia’s current tax system will pay close attention to those potential behavioural responses too.

Recent Comments