Australia is currently in the pilot year of a nation-wide university-based, pro bono tax clinic program to assist taxpayers who would otherwise not have access to tax advice and support. Further, the program provides a valuable learning experience by developing the technical and professional skills of university students.

Following the successful prototype initiated by the Curtin University (Western Australia, WA), which launched in July 2018, the Federal Government selected an additional nine universities to participate in a pilot. Specifically, these additional universities are (in order of State/Territory): Australian National University (Australian Capital Territory, ACT), UNSW Sydney (New South Wales, NSW), Western Sydney University (NSW), Charles Darwin University (Northern Territory, NT), Griffith University (Queensland, QLD), James Cook University (QLD), University of South Australia (South Australia, SA), University of Tasmania (Tasmania, TAS), and Melbourne Law School (Victoria, VIC).

However, ongoing funding for this program at the conclusion of the pilot is contingent on the successful outcome of the Federal Government’s evaluation of all ten clinics across Australia in time for the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, to be released next month.

One of the challenges for policymakers in evaluating this pilot is the identification of appropriate assessment criteria, given the relatively short time period that the clinics have been operating. The nine additional universities that have launched tax clinics have been established for substantially less than one year (variously opening between March and August 2019). In this pilot year, the universities have devoted substantial effort and expertise to the initial set up of the clinics. This investment has included designing (or adapting) programs to enable student participation in the clinics, obtaining pro bono support from industry and community organisations, advertising the clinics in the community, and ensuring compliance with relevant legal requirements (for example, obligations under the Privacy Act).

While many of the tax clinics have already developed promising client bases, as clinics continue and expand their operations over time they will likely further penetrate the market of taxpayers that could potentially benefit from the tax clinics. More broadly, even with any longer term or ongoing assessment of the clinics (assuming that funding continues beyond the pilot phase), it is suggested that the ‘success’ of the tax clinics should not be determined or limited by quantitative operational metrics such as gross client numbers or dollars of tax debts managed, which have sometimes been used in the United States (for example, per the Low Income Taxpayer Clinics Report, p.3). A key pitfall of this approach is that it results in blind spots in a number of areas such as the quality of tax services provided, the learning experience of tax clinic students, and the positive social impact generated by such programs over the short-, medium- and long-term.

So, how can positive social impact be created, measured and evaluated?

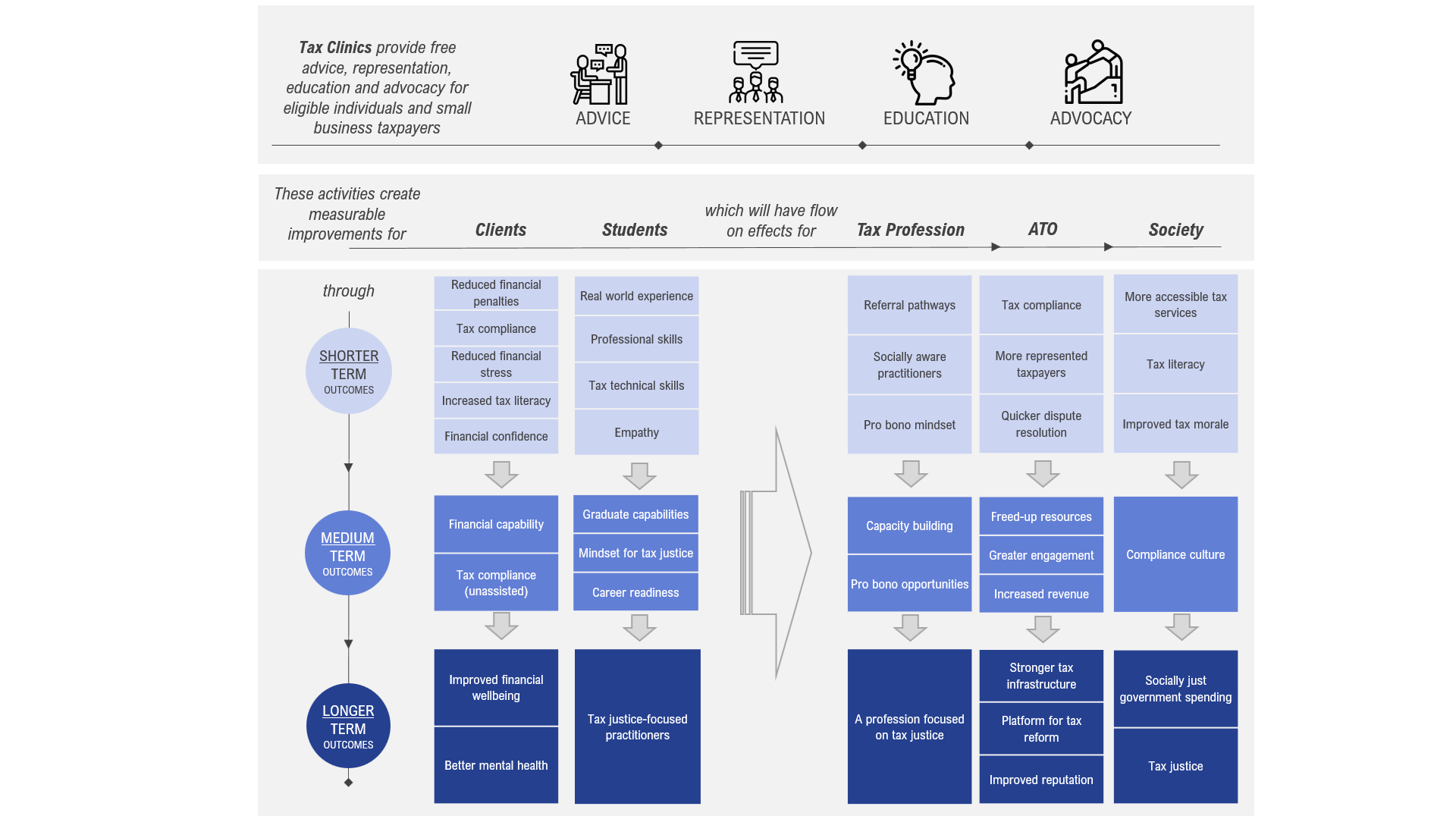

As recently described by the Australian Government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Program Logic is a thinking, planning and implementation tool that describes and diagrammatically represents how a project, programme or strategy intends to impact social, economic and political development in a given country, region or context”.

While the use of logic models and theory of change is utilised in the evaluation of investments by government departments and programs and even some community legal centres, such evidence-based models have not yet been adopted in the tax clinics literature.

The inaugural conference of the national tax clinics program, funded by the Australian Tax Office (ATO) and hosted by UNSW Business School on 19-20 June 2019, presented an opportunity to extend the existing literature in this space. With the guidance of the UNSW’s Centre for Social Impact, all ten universities co-created a program logic model for evidence-based evaluation of university-based pro bono tax clinics (the ‘Tax Clinics Program Logic’).

The co-creation of the Tax Clinics Program Logic involved a five-step process. First, the conference participants (comprising clinic directors and other academics involved in the establishment and operations of their respective clinics) were given a briefing on evaluation, outcomes and program logic design concepts. Second, participants were asked to map the anticipated outcomes for the five key stakeholders; namely, clients, students, tax professionals, the ATO and society. Third, participants were asked to review and select which of the other nine tax clinics’ outcomes resonated with the outcomes for their own tax clinic. Fourth, subsequent to the conference, the anticipated outcomes were aggregated across each participant’s preferences for each of the other nine universities, with the most popular themes extracted. Finally, the draft Program Logic was circulated for approval and comment across the cohort of ten universities.

The Tax Clinics Program Logic is shown in the below Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Tax Clinics Program Logic

(Click to enlarge)

The Tax Clinics Program Logic recognises that clients are a diverse group with different needs and requirements. As such, outcomes might differ in type and timing for different groups (older people, young people, different cultural backgrounds, Indigenous Australians, people with mental health illness, those living in different locations and with different vulnerabilities).

Importantly, the benefit of university-based pro bono tax clinics is not just in improved tax compliance at the individual taxpayer level. Indeed, the activities of the tax clinics also extend to free community education to increase the tax literacy of Australians (for example, workshops on how to access and use the ATO’s portal) and grassroots research to advocate for tax reforms grounded in tax justice.

As illustrated in the Tax Clinics Program Logic, the ultimate benefit of tax clinics is in creating a more socially just tax system. The cohort of 10 tax clinics nation-wide seek to achieve this by building the capability of our clients, our student volunteers and the profession to operate with tax justice at the forefront. Some anecdotes from this pilot year underscore the point that achieving tax justice cannot be measured by conventional quantitative metrics. Three groups of vulnerable taxpayers who have shown considerable interest in clinic services are the elderly, new migrants, and people living with mental health illnesses.

First, older taxpayers have deeply valued the opportunity to receive face to face help with their tax matters, specifically indicating that they either do not have access to the Internet or are not comfortable in using online services. Second, new migrants, in particular those who are still gaining English language proficiency, have sought guidance from the tax clinics, and the clinics have utilized translation services to meet their needs. In the United States, it is noted that taxpayers for whom English is a second language are specifically identified by policymakers as a group who are intended to benefit from tax clinic services. Third, there is a strong association between mental health problems and financial difficulties and clinics fill an otherwise unmet need in the community for people living with mental health illnesses by enabling them to obtain free and confidential advice which is independent of the ATO.

Essential components of the service delivery models employed by the tax clinics are also expected to engender tax justice (and social justice more broadly) by cultivating a pro bono mindset in students and providing a platform for skills-based volunteering opportunities for the tax profession. The involvement of university students in community service at a formative stage is expected to foster a long-term philanthropic attitude. The tax clinics also directly enable vulnerable groups to access valuable expertise that they could not otherwise afford since tax clinic students are in many cases supervised by professional tax accountants, who offer their time on a voluntary basis.

It is expected that these factors combined will deliver short-, medium- and long-term benefits to government, in particular to the ATO. Tax clinics have already assisted taxpayers who would otherwise not have engaged with the tax system. Further, given it is generally more difficult to deal with an unrepresented taxpayer than a represented one, tax clinics help to free-up ATO resources by providing otherwise unrepresented taxpayers with free and confidential advice from experienced, independent professionals.

In turn, as anticipated by the Tax Clinics Program Logic, the impact of tax clinics goes to the core of delivering positive social impact and achieving social justice. As observed by Afield (2019):

“Tax justice, however, is in fact a social justice issue. The most illustrative example of the social justice gains that can occur when tax justice is prioritized as an area of need can be found in the work of low-income taxpayer clinics (“LITCs”). LITCs engage in a combination of representation, education, and advocacy work that is essential in protecting taxpayer rights, securing economic benefits for the poor, and helping the vulnerable avoid having a tax liability impact their ability to obtain housing, healthcare, and/or employment.

Appreciating the social justice components of tax justice is not solely an academic issue of definitional precision — failing to understand the connection between tax work and social justice has negative societal consequences as well.”

The advent of the gig economy gives rise to unintended consequences for low-income taxpayers who are increasingly conceptualised as earning business income. This will disqualify them from services like ATO’s . So, in just the short-term at a societal level, tax clinics can assist in providing more accessible tax services, bolster tax literacy and improve tax morale. This will in turn assist the ATO’s mission of fostering a culture of voluntary compliance in the medium-term, and likely lead to improved outcomes for tax justice in the long-term.

Ultimately, it is hoped that the Tax Clinics Program Logic will assist both researchers and policymakers in Australia and overseas in their implementation and evaluation of university-based pro bono tax clinics. By providing an agreed framework for designing and conducting a robust evaluation, the Tax Clinic Program Logic will help us to understand how well university-based pro bono tax clinics are functioning, delivery challenges, and how and where improvements can be made.

Co-authors: We acknowledge the contribution of the academics across all ten universities involved in the National Tax Clinic pilot and a special thanks goes to the following academics who contributed to this piece (in alphabetical order): Mr Donovan Castelyn, Dr Michelle Cull, Professor Brett Freudenberg, Associate Professor Sunita Jogarajan, Ms Van Le, Mr Gordon Mackenzie, Mrs Annette Morgan, Dr Connie Vitale, Dr Sonali Walpola, Professor Michael Walpole and Dr Rob Whait.

TheTax Clinics Program is an excellent idea. It’s long overdue and I believe it will reap some wonderful results for researchers. Ordinary taxpayers are at a big disadvantage and many have no idea about their tax obligations. Tax education should start in secondary schools and be continued on via free community neighbourhood law centres.

Thanks Wayne – and I absolutely agree with you, CLCs would a great fit for tax law rights-based education.