Amalgamation is a popular tool for local government sector reform. Amalgamation of councils is employed frequently by Australian State governments seeking to increase council efficiency, on the basis that larger local governments will be able to provide services to residents at a lower cost. The catch is that available research suggests that these expenditure reductions often fail to materialise.

One explanation for failing to achieve expenditure reductions is that economies of scale do not exist in local government. Another is that amalgamation creates opportunities for spending reductions, but savings depend on actions taken by local decision makers. Determining which scenario is true is an important policy question particularly in Australia, where amalgamations are often met with fierce opposition from local politicians and their constituents.

My recent research estimates the effect of amalgamation on expenditure outcomes for New South Wales councils. In my paper, I examine the effect for councils that opted into consolidation and councils that were forced to consolidate, in the last decade, and also draw on historical data. Key findings are:

- Forced consolidation did not reduce spending in any expenditure category studied (total expenditures, employee costs, materials and contracts or other expenditures);

- Voluntary consolidation resulted in significant declines in total and other expenditures, but not in employee costs.

Australian local government and mergers

Amalgamation has a long history in Australia. The number of councils in NSW was reduced from 224 to 177 between the 1960s and 1990s. Council mergers were almost always initiated by the Minister for Local Government and did not require (and often lacked) the consent of the councils involved. As a result, councils were passive partners in the amalgamation process. For the forced NSW council mergers that took place in 2004, a study found that no planning was undertaken at either the State or local government level for implementation or support of the amalgamation (Jeff Tate Consulting 2013).

An exception to the status quo is a number of ‘voluntary’ mergers that occurred between 2000 and 2001. In 1999, the NSW state government invited councils to participate in structural reform, resulting in eight councils amalgamating to form four new councils (Armidale Dumarseq, Richmond Valley, Conargo Shire and Canada Bay). A critical difference between these voluntary mergers and later forced mergers in 2004 is that the continued support of each to-be-merged council was required if the merger was to occur (Tiley & Dollery 2010).

The quasi-experiment

Drawing on data from financial reports submitted annually by councils to the NSW Office of Local Government over the period 1996 to 2011, I studied the voluntary mergers of the early 2000s and forced mergers taking place in 2004.

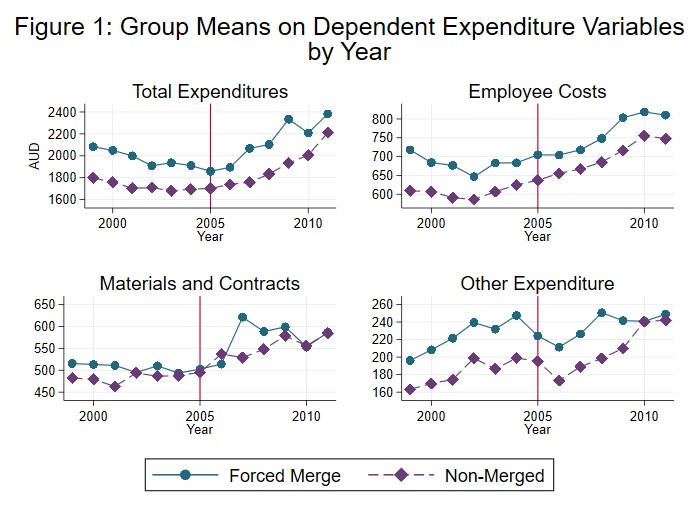

The statistical analysis compares pre-merger and post-merger spending outcomes in amalgamated councils, netting out any changes not resulting from consolidation. The latter is accomplished through use of a control group – councils that were not involved in a merger during the sample period. Trends in spending over this period by forcibly merged and control councils are depicted in Figure 1.

Forced mergers do not reduce council spending

Forced mergers do not reduce council spending

The year 2005 was the first year in which amalgamated councils submitted a financial report. There are two insights to be drawn from Figure 1. First, in the years preceding merger, total expenditures were actually decreasing in amalgamated and non-amalgamated councils. Second, relative to the control councils, there is no visibly discernable decrease in spending in the amalgamated councils.

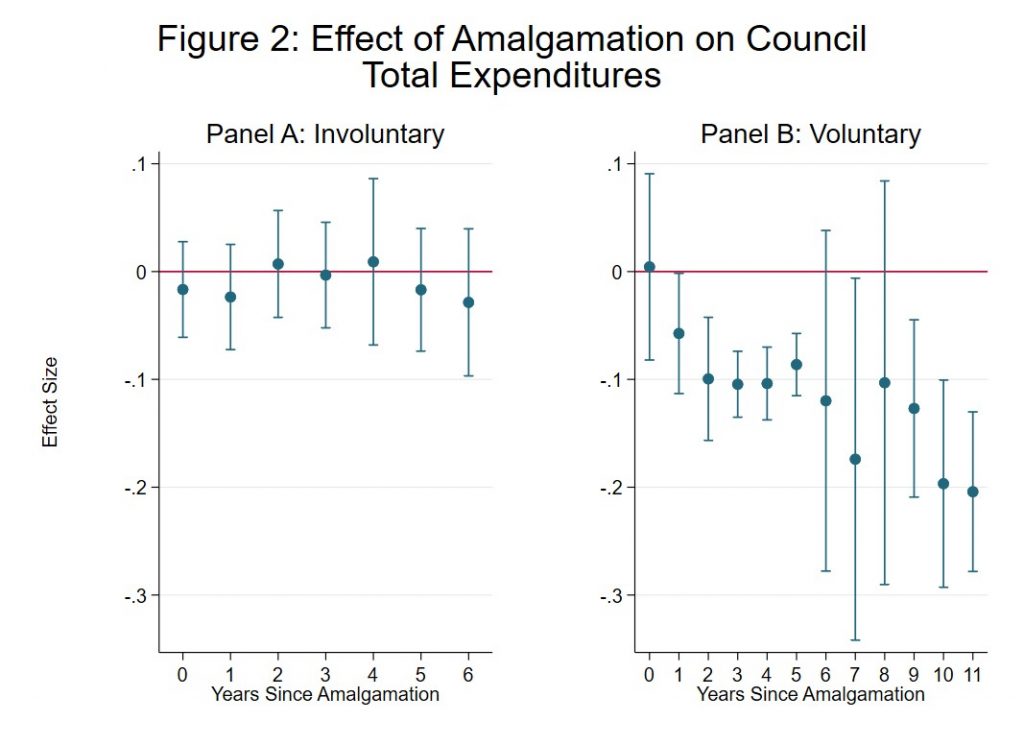

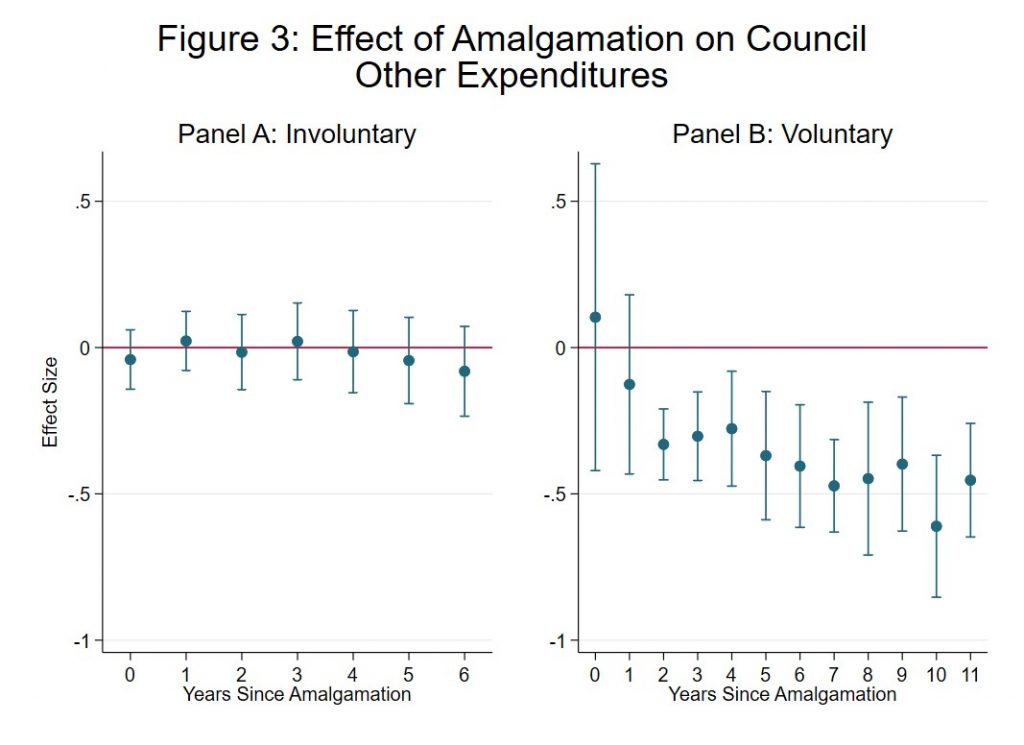

This visual interpretation of Figure 1 is confirmed by a multivariate regression estimating the effect of amalgamation on spending outcomes in each year following merger. Figures 2 and 3 depict the estimates for total and other expenditures respectively (estimates for materials and contracts or employee costs are not shown because amalgamation did not reduce in spending in these categories).

On the x-axis, “0” represents the first year the new council was in operation. A value of “0” on the y-axis indicates that amalgamation had no effect on spending, negative values represent percentage reductions in spending. The brackets surrounding each estimate represent the confidence in the estimate; if these brackets cross “0” on the y-axis, the effect estimate is not distinguishable from zero and we cannot claim that amalgamation had an effect on spending.

Results for forced amalgamation are depicted in Panel A of Figures 2 and 3, and show that forced amalgamation did not reduce council expenditures in either spending category.

Results for forced amalgamation are depicted in Panel A of Figures 2 and 3, and show that forced amalgamation did not reduce council expenditures in either spending category.

On the other hand, councils that amalgamated voluntarily experienced significant declines in total and other expenditures following the merger. For example, voluntarily amalgamated councils experienced on average a ten percent reduction in total expenditures two years following merger (Figure 2). A similar pattern is observed in other expenditures (Figure 3), voluntary amalgamation results in significant and sustained decreases in spending. Again amalgamation had little to no effect on spending in forcibly merged councils.

On the other hand, councils that amalgamated voluntarily experienced significant declines in total and other expenditures following the merger. For example, voluntarily amalgamated councils experienced on average a ten percent reduction in total expenditures two years following merger (Figure 2). A similar pattern is observed in other expenditures (Figure 3), voluntary amalgamation results in significant and sustained decreases in spending. Again amalgamation had little to no effect on spending in forcibly merged councils.

Achieving cost savings requires buy-in

The overall finding of my research is that councils that merged voluntarily were able to reduce spending while forcibly merged councils were not. This is due to stark differences in local council involvement in the merger process. It seems that increasing council size creates opportunities for councils to reduce expenditures, but it is not sufficient. Achieving cost savings requires that local officials ‘buy into’ and participate in the amalgamation process.

Thus, the relevant policy question is not ‘should state governments pursue consolidations as a method of local government sector reform?’, but rather ‘how can municipal consolidation policy be designed and implemented so that mergers achieve their intended outcomes?’

Further reading: Mughan, S 2019, ‘When do municipal consolidations reduce government expenditures? Evidence on the role of local involvement’, TTPI Working Paper 3/2019, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, The Australian National University, Canberra.

Dear Sian,

Thank you for a very informative article. I (Grant) am gaining as much info as possible on Forced Amalgamations as Tasmania is going through this process again. I live in Tasman Council -roughly 2,600 rate payers & in 2018/2019 we voted on amalgamation. Over 70% voted NO. I was 1 of the main people pushing against Amalgamation. Our Council has over $3 million in the bank & our population is growing by 2% annually.

Your info here is great & I will share it with our Mayor shortly.

Cheers

Grant

PS: feel free to offer suggestions if you wish & have time.