When the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) introduced the e-filing and pre-filled income tax data systems, the ambition was bold: increasing compliance behaviour; reducing the complexity of the tax system; and reducing compliance costs. These costs included the cost of managing tax affairs (or item “D10” in the tax return). However, more than a decade after introducing the e-filing, the figures related to D10 deductions tell us a different story.

In a recent article for the Australian Tax Review, published by Thomson Reuters, we used the ATO data for individual taxpayers to analyse the longitudinal trends in D10 deductions over the two main means of tax lodgement in Australia, e-filing and tax agents. We find that while the implementation of pre-filled income data coincides with a reduction in the number of e-filers claiming D10, it had no impact on the number of D10 claimers lodging via tax agents, and little to no impact on the actual costs incurred. Importantly, there was a surprising twist in how much e-filers are claiming.

A promising reform with unexpected outcomes

To boost tax compliance and reduce compliance costs—including the cost of managing tax affairs—the Australian government rolled out pre-filled income data in 2008-09 and launched myTax via myGov in 2013–14. These initiatives were designed to simplify lodgement by electronically pre-filling income data that the ATO already held. Our findings show they succeeded in reducing the share of e-filers claiming the D10 deduction (from 13.1% to 5.4%).

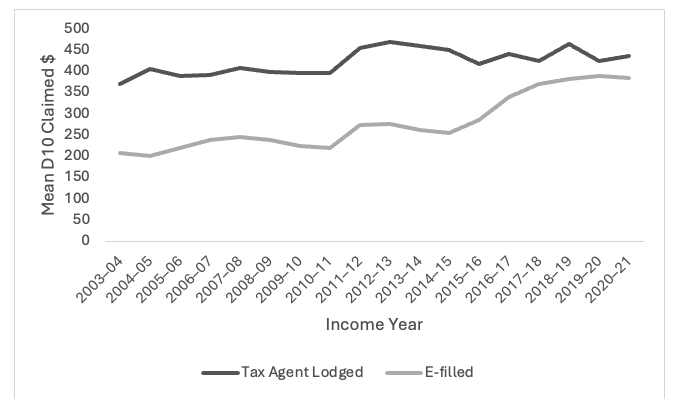

Despite fewer e-filers claiming the D10 deduction, those who do are now claiming more than they did two decades ago. Our findings reveal that the average amount of D10 claimed by e-filers increased by 84% between 2003 and 2021, compared to an 18% increase among tax agent users (see Figure 1).

Interestingly, low-income e-filers are claiming higher amounts than their high-income counterparts. A portion of these e-filers report no tax liability at all, prompting questions about whether these patterns reflect underlying compliance challenges and misuse of the tax provision, or simply a result of difficulties navigating the e-filing system, resulting in questionable claims rather than deliberate non-compliance.

Figure 1: Mean D10 claimed by lodgement method between 2003 and 2021

Source: compiled from ATO. Note: dollar amounts were CPI-adjusted.

The prior debate on capping D10

In 2018, the Australian Labor Party proposed to cap D10 deductions at $3,000. While the proposal was ultimately withdrawn, the idea continued to attract both media and academic attention, with some commentators supporting the reform and others expressing their concerns about its potential ramifications.

Our analysis offered insight into this debate, emphasising that less than 0.5% of the D10 claimers claim more than $3,000, with 97% of these taxpayers lodging their tax return through tax agents.

However, a closer examination of the data reveals a notable shift: the number of e-filers claiming more than $3,000 increased by 9% between 2003 and 2021, while the percentage of high D10 claimants lodging through tax agents declined by 4.6%.

We estimated that if the cap is implemented, the government could raise $188 million annually. However, focusing only on the revenue gain could distract the government from long-term shifts in the compliance habits of taxpayers, particularly the rising numbers of high D10 deductions claimed by e-filers. Failing to account for these evolving compliance behaviours risks undermining the ATO’s digital reforms strategy, leaving long-term vulnerability in the tax system unaddressed.

What this means for policy and practice

Our results indicate that digital reform has altered the way taxpayers manage their tax obligations, but it has not fully eliminated the compliance burden. There is also no suggestion that taxpayers, particularly e-filers, are necessarily engaging in non-compliant behaviour.

While the ATO introduced e-filing and the pre-filled system to increase compliance, reduce the complexity of the tax system, as well as the compliance cost, our findings suggest that, more than a decade after their implementation, D10 deductions reveal outcomes that diverge from the original expectations.

Ultimately, we need to contemplate categories that are captured within the D10 claims. In particular, whether the costs relate to (1) compliance and advice by a registered tax agent, (2) costs associated with disputes/judicial processes, (3) general and shortfall interest charges, and (4) indirect costs such as travel. Naturally, the category of cost will depend on where a particular taxpayer is in the lifecycle of tax administration as well as technology adoption.

With this in mind, the government has subsequently taken the approach of capping D10 in full. From 1 July 2025, taxpayers will no longer be able to claim as part of their D10 deduction the general interest charge (GIC) and shortfall interest charge (SIC). This follows the passing of Treasury Laws Amendment (Tax Incentives and Integrity) Bill 2024. Treasury described this move to restrict D10 as seeking “to reinforce the requirements imposed on all taxpayers to correctly self-assess their income tax liability, pay their tax on time, and assist in lowering the amount of collectable debt owed to the ATO” (paragraph 1.2). Further examination of the impact of this restriction is warranted. There is a plethora of debate over the approach.

Overall, the findings observed in D10 deductions revealed that while the ATO’s digital reform achieved some of its intended outcomes, it also may have triggered new behavioural dynamics that merit attention. In this context, D10 represents more than a deduction item; it underscores how technological adoption within the taxation system is reshaping the way Australians meet their tax obligations. This has important implications for future tax reform.

Recent Comments