A 2013 study by Hill and Thee shows that only 25 per cent of Indonesians aged 19-24 years are enrolled in higher education. Of those, 55 per cent came from the richest quintile, while only 2.6 per cent came from the bottom quintile. In addition to unequal access to higher education, utilisation of higher education scholarships is still low in Indonesia. The government’s flagship higher education scholarship program (Bidik Misi) covers only 5.6 per cent of all undergraduate students.

In a cabinet meeting in mid-March 2018, Indonesian President Joko Widodo encouraged banks to disburse loans for students pursuing higher education to boost the quality of human resources in the long run. The hope was that access to higher education loans would alleviate poverty.

The proposal received mixed responses. Several parties, including the Minister of Research, Technology, and Higher Education, M Nasir, were skeptical of the idea. One of the concerns was that it could lead to widespread default, which in turn could slow down Indonesia’s economic growth.

The minister’s pessimism is not without basis. In many countries, loans to finance higher education have resulted in high default rates. The US is an important example. The country uses a so-called mortgage-type, or time-based loan system, which means a loan must be repaid within a set period. Many countries, including the US, have experienced widespread default with this loan system. The main reason is the very high repayment burden (the ratio of debt repayments to income) associated with mortgage-type loans. Studies find that a repayment burden above 10% is likely to lead to high loan default rates.

Indonesia had an experience with a mortgage-type loan system in the 1980s. It was a complete failure with the default rate reaching 95 per cent. This traumatic experience discouraged many banks, even state-owned ones, from responding to President Widodo’s call.

However, there is a different loan system that the Indonesian Government could consider, which is the income contingent loan system. Under this system, the repayment period is not set in advance and repayment starts only when the debtor’s income is above a certain threshold. The Government can collect debts using employer withholding which is regulated under Directorate General of Taxation. This is the same mechanism used by the Government to collect income taxes and social contributions.

The repayment burden is designed to be at a low rate. Nominally, repayment increases along with the increase in income. During periods of unemployment or recession, income would fall under the repayment threshold, thus repayments are postponed. This way, the system protects against default.

The system has been implemented in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. In these countries, the repayment burden is set at a lower rate (around 8-11 per cent). At this rate, debtors still have enough disposable income to make ends meet and avoid payment hardships.

Simulation and findings

In our article, we simulate the implementation of income contingent student loans in Indonesia. We use income data projections of 11,300 university graduates in Indonesia, from a nationally representative labour force survey. We calculate the loan repayment period, the total amount of loan, and the implicit subsidy that the Government would have to provide using the loan system. Even with full repayment, the loan system must still be subsidized by the Government as it finances the loans in advance. But such subsidy is often not observable, hence the term implicit subsidy. It is the gap between the nominal value and the real value of the repayment.

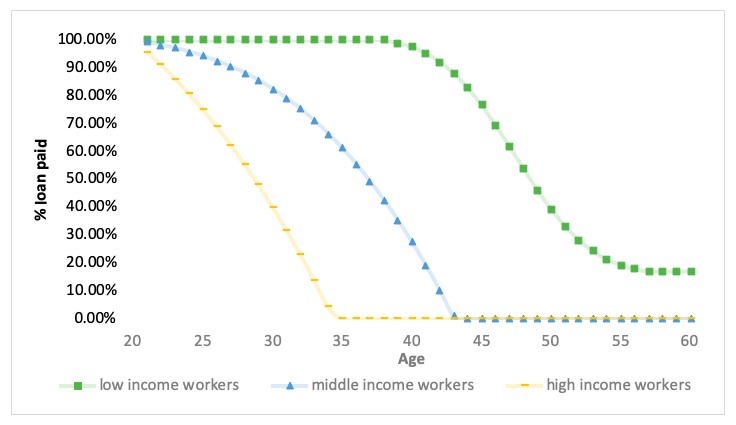

We model two types of repayment burden. The debtors are set to pay 8 or 10 per cent of their income each month. The simulation shows that male graduates from all income groups can start to repay their debt within the first year after graduation, and they will be able to complete the loan repayment within 25 years. Figure 1 shows the simulation results for females. For low-income female graduates, the loan repayment starts two or three years later with a possibility of default after 25 years, especially when the monthly repayment burden is set at 8 per cent and a real rate of interest or a surcharge of 25% is added on top of the total loan.

Government subsidies will be lower if a positive real rate of interest or a surcharge is applied. But charging interests may not be equitable since the interest expense incurred will be higher for low-income graduates because of the accumulation of interest payments over time. Imposing a surcharge (as in the Australian system) would probably be the best scheme in which most of the debtors can finish repayment within 25 years while implicit government subsidies remain relatively low. But still, the subsidies for female graduates will always be higher because of the gender wage gap and higher unemployment rates among females.

Figure 1: Share of loan repaid during working age by income group

Note: This graph is based on a scheme of total debt of Rp 60 million (including a 25% surcharge), or around AU$ 6,299, for a 4-year undergraduate degree. It is assumed that female graduates who are in debt have graduated at age 21. The loan repayment rate is set to 8% of the monthly income.

Our results show that implementing an income contingent loan system for higher education in Indonesia is feasible. The second finding is that in order to create a sustainable student loan system, the Government must be willing to subsidise borrowers, especially women.

Potential issues

Many things must be considered when applying an income contingent loan system in Indonesia. The country’s gender wage gap, low labour absorption, low female labour force participation rate, a reliable tracking system for graduates, and a high variation in university quality are among the issues that have to be addressed.

The implementation of income contingent loan has so far been proved effective in countries where everyone’s income is reported to the government through the tax system. The Indonesian tax system is still considered far from effective, although it has improved over the last decade. As in the context of income taxation, government insurance and other social security contributions, the Indonesian Government can utilise employers to withhold loan repayments from university graduates if they are to implement the system.

Although it may not be easy in Indonesia, an income contingent student loan system can provide an opportunity for a fundamental change in the future of Indonesia’s children. Providing equal access for Indonesian children to higher education would ensure that attending university is not just an option for those from privileged families but a right for everyone.

This article is a summary of a forthcoming Higher Education by Elza Elmira and Daniel Suryadarma, Financing tertiary education in Indonesia: Assessing the feasibility of an income-contingent loan system.

Blog articles on Indonesia

Minimising Potential Tax Avoidance by Strengthening Transfer Pricing Policy in Indonesia, by Maria RUD Tambunan, Haula Rosidiana and Edi Slamet Irianto (11 February 2020)

Do Tax Structures Affect Indonesia’s Economic Growth?, by Heru Iswahyudi (4 November 2019)

Local Legislature Size Effects in Indonesia: Pork Barrel or Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen?, by Blane D Lewis (1 October 2019)

Recent Comments