The Coalition’s Super Home Buyer Scheme is slated to enable first homebuyers to use 40% of their super balance, up to a maximum of $50,000 for the purchase of a home, whether brand new or existing. We use the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO) 2% individual taxpayer data for the 2019 income year, to examine how much taxpayers could actually access given their super balances. We also consider the scheme’s interactions with gender and tax policy.

The Super Home Buyer scheme

The scheme’s criteria is relatively simple. The buyer must be a first homebuyer, and the buyer must also have saved a 5% deposit separately.

There is no cap on income and no cap on property.

The Coalition expects this scheme to allow sufficient deposits to be saved three years sooner.

Buyers’ retirement savings are protected by requiring that the withdrawn super be returned to their superannuation fund when the house is sold as well as contributing a share of any capital gain made.

There have been a range of criticisms to the policy since its announcement. These have been particularly directed towards the impact on house prices – the scheme leading to worsening affordability without leading to an increase in ownership rates.

Concern has also been raised regarding those under the age of 40 having sufficient superannuation to access the full $50,000. Even if they do, concern has been raised as to the requirement of returning the principal and share of capital gain to the fund. This may render the homebuyer locked into the property as they may not be able to afford moving on without the use of that equity.

Some suggest that women will be the biggest ‘losers’ in this scheme, given that they generally have on average lower super balances. This has been raised numerous times, including by the Grattan Institute, The Tax Institute and Australian Super; the latter finding men retire with approximately 42% more superannuation than women.

Mean and median super balances by age and gender

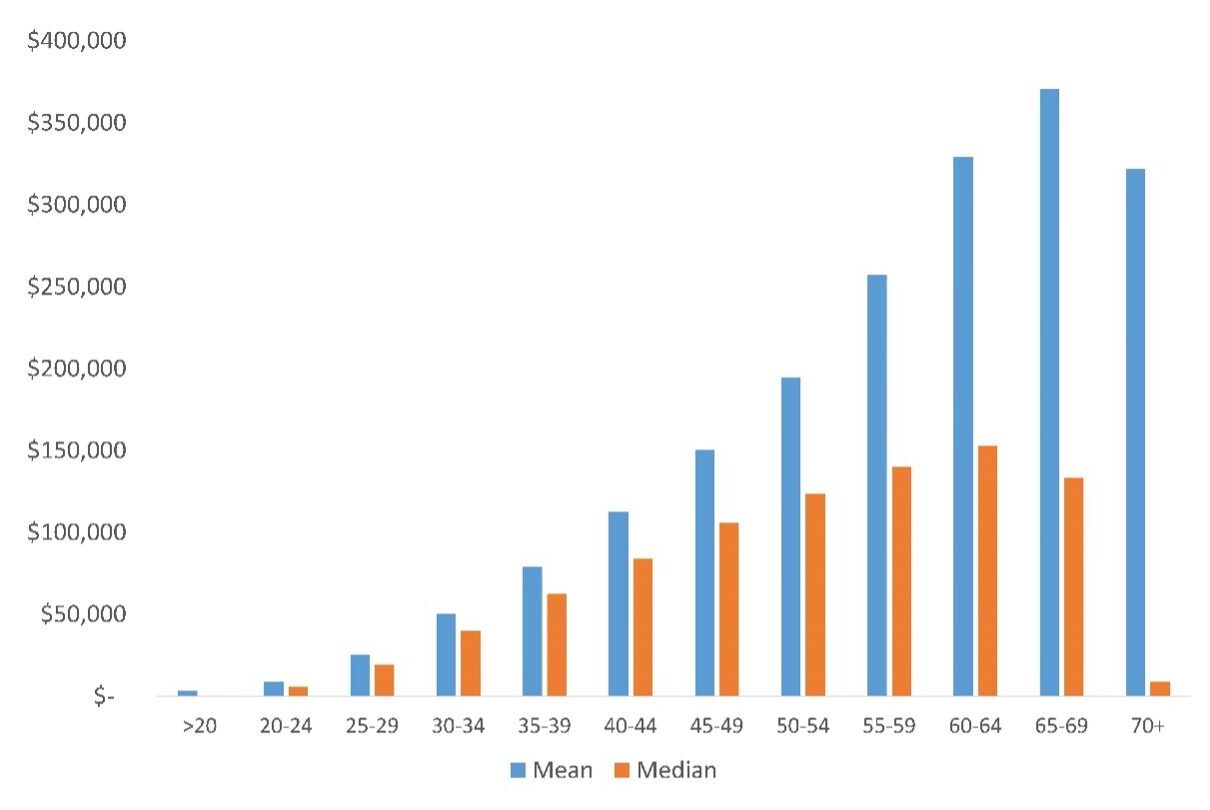

Whilst recognising that 3.5 million Australians took out over $36 billion from their super following COVID-19, Figure 1 depicts the mean and median super balances as at 30 June 2019.

Figure 1: Mean and median superannuation balances 30 June 2019, by age

Source: Australian Taxation Office

The mean balance peaks at $370,625 for 64–69-year-olds, whilst the median balance peaks at $152,985 for 60–64-year-olds.

Assuming first-homebuyers are largely represented by younger age groups, the mean balance for 30-34-year-olds is $50,250 (median $39,747).

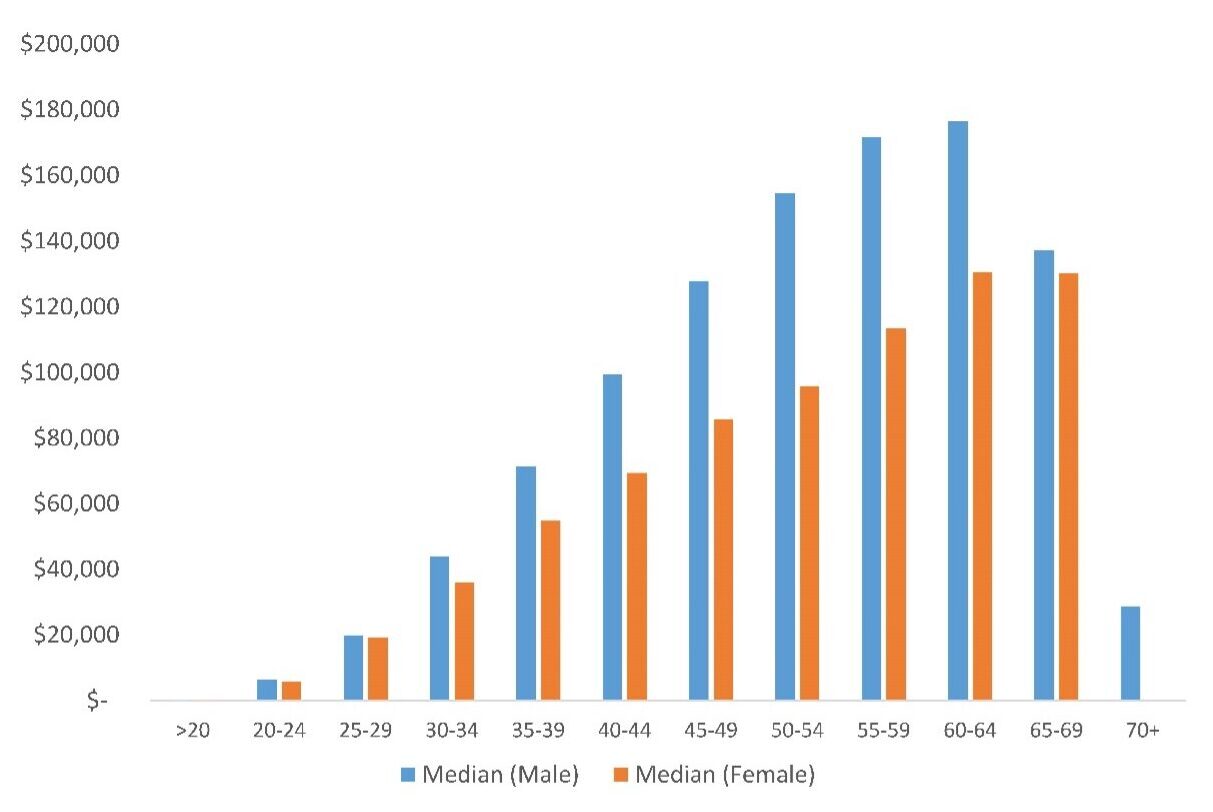

The disparity between gender is clear, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Median superannuation balances 30 June 2019, by age and gender

Source: Australian Taxation Office

The gender gap is smallest for the 25–29-year-old bracket (4.5%). However, by the 30–34-year-old bracket, it has increased to 22%, with males having a median balance of $43,836 and women $35,930.

This gap keeps increasing through to 61.2% by the 55–59-year-old bracket.

Whilst the median superannuation balance for men aged 70+ is $28,790, the median balance for women is $0. This seems to be more of a relationship status effect than gender, as will be noted below.

Implications of females being married or de facto

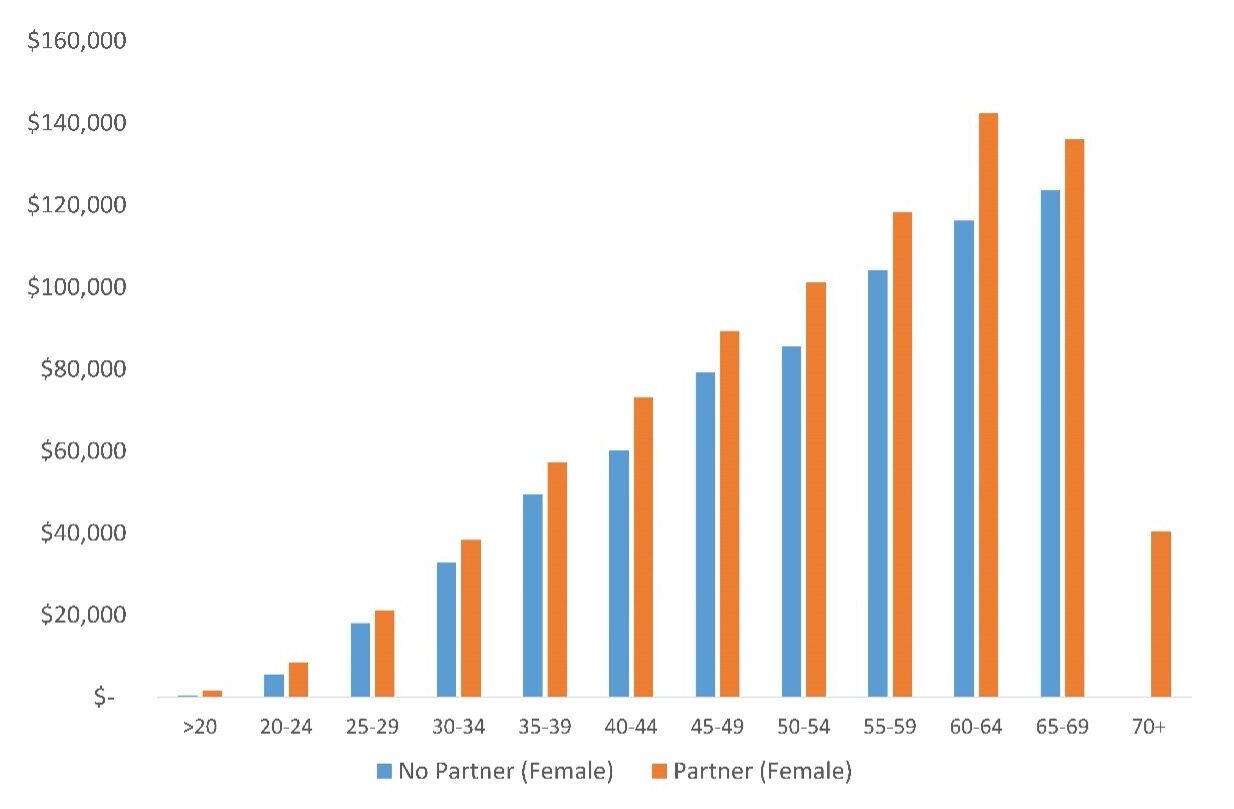

Scott Morrison made specific reference to single mothers. Although the ATO data does not capture children, it captures partner status (married or de facto).

Here, we focus on women. Figure 3 presents the breakdown of median super balances of females by partner status.

Figure 3: Median superannuation balances 30 June 2019, females partitioned by partner status

Source: Australian Taxation Office

For women aged 30-34 with partners, their median superannuation balances are $38,338, 16.6% higher than females without partners (at $32,870).

From 25 years of age upwards, there is a consistent difference of between 15 to 20% until the 70+ age bracket. Women with partners in this age bracket have a median superannuation balance of $40,511 compared to a median of $0 for women without partners.

It is worth reiterating here that this data is pre-COVID. We recently reflected on women and young people and the impact of the pandemic and their ability to see real growth in wages – a fundamental input to building retirement savings.

What does this mean in terms of buying a first home?

Using the median super balance for 30-34-year-olds of $39,747, 40% of super that could be accessed by first homebuyers under this scheme is $15,899.

Given the current median property price in Australia is $738,975, a 20% deposit equates to $147,795.

Nearly half of the homebuyers’ super balance represents merely a 10.8% portion of the necessary deposit. Homebuyers will still need to find $131,000, well beyond the required 5% to access the scheme (putting aside the ability to borrow more whilst incurring mortgage insurance).

This is not an insignificant amount of money.

For the scheme to work (enable home ownership and increased retirement savings), this requires a continuation – if not a worsening – of housing affordability.

Whilst the Coalition has not directly revealed what occurs if house prices fall, the Guardian suggests that the repayment back to the super account will decrease proportionately.

Many questions remain unanswered

It is certainly assumed here, that the capital gain reflects the capital gains tax (CGT) regime found within the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA97).

The main residence is generally exempt from capital gains tax, taking the pressure off households from keeping detailed records of incremental spending (such as repairs, maintenance and improvements) to the property.

Any tax practitioner appreciates the challenges in compiling records for the family home. Consider yearly interest expenses, rates and insurance.

All of these non-capital costs of ownership, as well as improvements, form part of the CGT cost base of the home.

Overtime, these will dilute the proportion of the cost base relating to the initial super principal. When the Coalition indicates that a ‘share of the capital gain’ is needed to be deposited back into the super fund when the property is sold – what basis ought this to be apportioned on?

The CGT implications are further impacted by numerous factors, such as tax residency status and use of the property (where the main residence maybe reduced in part or in full). In some instances, deeming rules shift the cost base of the home to the market value at a particular point in time, essentially ignoring original acquisition details.

These create a clear disconnect with initial contributions and tax implications.

Should any tax incurred be considered when determining the capital gain to be added to the super?

CGT is not a separate tax though; it simply forms part of income tax. This adds a further element of apportionment thus room for interpretation – and room for error.

Yet – this is all assuming a gain is made…

Does a gain represent cash actually available to contribute?

What about taxing points of contributions going into the super fund?

There are many complex nuances between gender, tax and super to unpack when considering what appears to be a fairly straight forward scheme to address housing affordability. Like all things, the devil is in the detail – which is yet to be revealed and is pending the Coalition returning to power.

Recent Comments