In Australia, as in many high-income countries, population ageing is inexorable. One potential consequence of ageing of the population is a shift in income inequalities, which may lead to energy poverty. Fixed and often relatively low incomes and the need for additional energy due to underlying health conditions make energy poverty a particular problem for older people. If energy poverty worsens the health of older people, this can have cost implications for the healthcare sector. It is therefore important to understand the incidence and drivers of energy poverty among the older population.

Retirees in Australia can be categorised by their income source as: a) Age Pensioners who are fully funded by public transfers, b) part-pensioners whose pension rates are reduced by a means test or c) self-funded retirees, who derive their income from superannuation accumulated during their working life and perhaps income streams from property investments. Differences in income levels and government transfers may lead to energy poverty through different income sources. For example, additional (government-funded) benefits such as energy supplements included with the Age Pension could make Age Pensioners better off than self-funded retirees, even if they had the same income level. This is especially the case as several other concessions (for example, health, municipal) are tied to being an Age Pensioner.

The division of retirees into three categories potentially leads to differences in energy poverty due to factors other than income. We used 15 waves of the annual Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey from 2005–2019 to investigate drivers of energy poverty inequalities among different types of retirees.

How do we measure energy poverty?

Objective measures of energy poverty may provide a more accurate measure of energy poverty (unless low-income retirees have the means to limit energy expenditure). However, subjective measures of energy poverty capture the ‘feeling’ of energy poverty. Since these two measures may not coincide, we explore both objective and subjective measures of energy poverty.

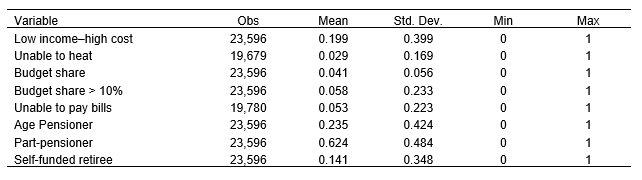

Our objective measures are the low income–high cost (LIHC) indicator of energy poverty, the energy budget share, and an indicator of whether this budget share exceeded 10% (a traditional energy poverty measure). Our subjective measures are an indicator of an inability to heat the home due to a shortage of money and an indicator of an inability to pay electricity, gas or telephone bills on time due to a shortage of money.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for key variables

Age Pensioners more likely to be energy poor

Using the objective measure of energy poverty and the subjective measure of the inability to heat the home, we find self-funded retirees fare best and Age Pensioners fare worst, with part-pensioners in the middle. However, according to both budget share measures of energy poverty, self-funded retirees are more likely and Age Pensioners less likely to be energy poor when compared to part-pensioners. This result is likely due to Age Pensioners and part-pensioners having lower actual expenditure on energy due to the availability of energy supplements for which self-funded retirees may not qualify. It is also consistent with self-funded retirees choosing to spend more and Age Pensioners having more thrifty approaches to energy use and ‘making do with less’.

In terms of being unable to pay bills on time, our findings mirror those on the inability to heat the home: energy poverty is more likely for Age Pensioners and less likely for self-funded retirees. In terms of managing the costs of heating and having to restrict expenditure to manage competing demands on limited incomes, Age Pensioners are the most disadvantaged type of retiree.

In our analysis, it is important to rule out reverse causality whereby energy costs earlier in life affect retirement arrangements.

There are several reasons why reverse causality may not occur. In Australia’s superannuation system, although employer contributions are mandatory, employee contributions are not and very few individuals make voluntary contributions. This makes it unlikely that superannuation contributions during working life were significantly impacted by energy prices. Employer contributions are mostly influenced by occupation choices, as these compulsory contributions are a fixed percentage of salary. As most individuals choose an occupation relatively early in life when they are not responsible for energy bills, it seems unlikely that occupation choices would be determined by energy prices. Data for Australia also suggest the main reason for retirement from the workforce is reaching the age for eligibility to access superannuation or the Age Pension. This suggests retirement timing is not sensitive to an individual’s energy costs.

Consistent with these arguments, our modelling shows no statistical evidence of reverse causality. By extension, we can infer that our results capture the causal effect of retiree type on energy poverty.

Potential energy poverty mediators

We find wealth, assets, social connectedness and good health are all important mediators that lessen subjective worries about energy bills for retirees.

After controlling for income, there may be monetary effects on energy poverty through retirees’ wealth and assets as different levels of wealth and/or assets may impact energy poverty if retirees expend these resources towards energy costs. Social isolation works in a similar way — retirees associated with social isolation (through income effects) might have higher energy costs if they spend more time at home. Being socially isolated, they may also have less support from others to help pay bills when energy prices increase.

Finally, general health may be a mechanism affecting energy poverty as some retirees could have different health care costs leading to different health outcomes and ultimately different energy needs.

Targeted initiatives for different retiree types are needed

Age pensioners are the most likely retiree type to be at risk of energy poverty and targeted initiatives could address this problem. They are particularly vulnerable given that in the last 20 years growth in energy prices has outstripped growth in the Age Pension in Australia. The Age Pension is a safety net and therefore needs to be adjusted during energy price inflation.

To ensure equity among older Australians, consideration should be given to the welfare gap between state-funded pensions and self-funding arrangements. A fair and equitable society should allow all citizens to afford sufficient energy for healthy living and it is important that retirees’ health and wellbeing is not detrimentally affected by an inability to heat and cool their homes. New initiatives and current policies aimed at addressing energy poverty, such as concessions to energy bills or funding for targeted energy efficiency upgrades, should be reconsidered.

In summary, our analysis shows that the type of retirement funding arrangement is critical to energy poverty outcomes as not all retirees have the same risk of experiencing energy poverty. As energy poverty is a rising source in inequity for many countries, these lessons from Australia will be useful for other countries with an ageing population.

Further reading

Fry, J.M., Farrell, L. and Temple, J.B. (2021), Energy poverty and retirement income sources in Australia, Energy Economics, 106, 105793, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105793.

Recent Comments