Society often curses the two ‘unpleasant certainties’ in life, ‘death and taxes’. We rarely praise ‘life and taxes’, whereby taxes are recognized as instruments capable of supporting our existence rather than acting as mere burdens. This article presents a proposal from a substantial Canadian study that tax law holds the potential to play a major role in protecting the world’s finite fresh water supplies, without which, life on earth would not exist. Beyond the notion of ‘no water-no life’, many of today’s energy sources could not be produced without fresh water, and without energy, many of our social structures as they exist today would cease to exist.

Accessible fresh water (potable water) represents a miniscule portion of all of the water on earth. If the quantity and quality of this water deteriorate to a level that is insufficient for life sustaining purposes, the natural process of purification through the earth’s connected lakes, rivers, streams, and underground aquifer systems can take centuries or millennia to recharge. As we face ever-increasing demands on both water and energy production, these limits pose a real cause for concern.

The number of cubic meters of fresh water available per person globally has dropped over the past decades, while freshwater demands by industry for energy production purposes have increased. Industrial water withdrawals may be returned and recycled through the hydrologic cycle; however, in this process a portion of the water becomes ‘consumed water’, which means that it is no longer fit or available to serve as potable water. In Canada, over 9% of all water withdrawals are consumed each year, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that the water consumed through energy production globally will increase by 60% to 2040.

There is a conflict between the two viewpoints of what might be coined a two-headed dragon—‘water for life’ or ‘water for energy’.

These two viewpoints can be spun in a positive direction if they can be seen through the eyes of wisdom on the past and the future—as was the practice of the Roman God and gatekeeper, Janus. This would enable the rivalry between human and industrial needs for fresh water to be met with proactive wisdom rather than conflict. One approach is the development of new techniques to reduce the withdrawals of fresh water and the consumption of the withdrawals.

Janus

(Source: Flickr)

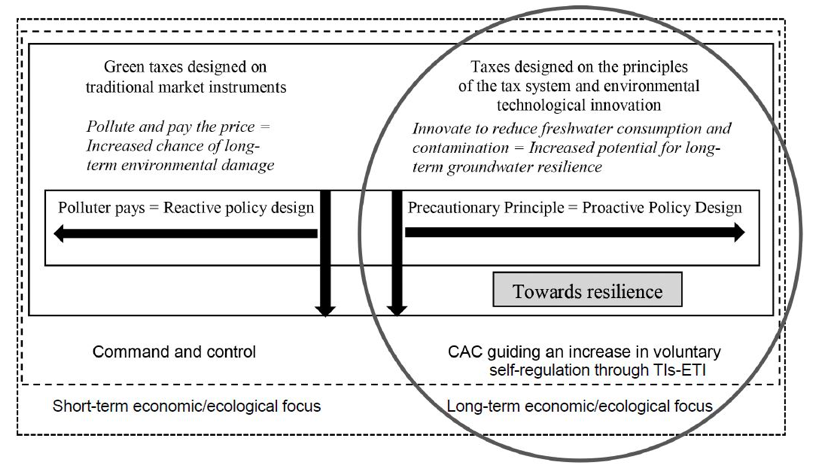

Tax policy may be one instrument of change for this shift from conflicting forces to cooperative models, and thus may be a means to preserve life. As examined in the study, the introduction of tax incentives for environmental technological innovation offers an alternative method of policy and regulation. These tax incentives would be partnered with government directives and stakeholder input to stimulate innovation and to operate proactively, in order to build resilience, rather than to punish reactively once the damage is done (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tax incentives for environmental technological innovation for freshwater resilience

This argument is grounded in theory which proposes that businesses should be held fiscally responsible for the damaging externalities they create, by way of an environmental tax. Arthur C. Pigou has long been considered a founder of environmental taxes, and as such, these taxes are often referred to as ‘Pigouvian taxes’. It is much debated whether it is the role of government or markets and individuals to address pollution; the argument often falls to the side of government when there are a large number of parties involved. Since this article looks at a global population depending on fresh water and energy production, the idea of a ‘tax’—rather than strict market forces—is explored.

As taxes frequently draw negative attention, it is important that the mechanisms be reframed as proactive incentives. Incentives to address pollution or environmental damage are often criticised as rewarding ‘bad behaviour’, so they should be carefully crafted as instruments promoting long-term resilience. While this design puts a twist on the original Pigouvian tax, it is only different in principle in that it encourages a front-end approach to externality reduction guided by stakeholder input, rather than back-end fines for ‘difficult to rectify’ pollution from single firms.

Further arguments abound as to whether government intervention should come in the form of tax policy or regulations. While regulations are often criticised for their inability to promote innovative ideas, they do play a role in the larger policy framework proposed here, as seen in Figure 1.

The particulars of tax policy proposed through tax incentives for environmental technological innovation are drawn from scientific research and experimental development programs, capital cost allowance systems, and other special programs in the tax law. Incentives and programs for research and development exist in many tax regimes around the world. In Canada, scientific research and experimental development is defined in the Canadian Income Tax Act s 248(1) as:

“systematic investigation or search that is carried out in a field of science or technology by means of experiment or analysis and that is

(a) basic research, namely, work undertaken for the advancement of scientific knowledge without a specific practical application in view,

(b) applied research, namely, work undertaken for the advancement of scientific knowledge with a specific practical application in view, or

(c) experimental development, namely, work undertaken for the purpose of achieving technological advancement for the purpose of creating new, or improving existing, materials, devices, products or processes, including incremental improvements thereto, and, in applying this definition in respect of a taxpayer, includes

(d) work undertaken by or on behalf of the taxpayer with respect to engineering, design, operations research, mathematical analysis, computer programming, data collection, testing or psychological research, where the work is commensurate with the needs, and directly in support, of work described in paragraph (a), (b), or (c) that is undertaken in Canada by or on behalf of the taxpayer,

but does not include work with respect to

(e) market research or sales promotion,

(f) quality control or routine testing of materials, devices, products or processes,

(g) research in the social sciences or the humanities,

(h) prospecting, exploring or drilling for, or producing, minerals, petroleum or natural gas,

(i) the commercial production of a new or improved material, device or product or the commercial use of a new or improved process,

(j) style changes, or

(k) routine data collection;”

The majority of eligible research and development in Canada falls under the definition of experimental development in paragraph (c). This may be the most likely category for innovations pertaining to freshwater protection. While the wording in paragraph (h) excludes scientific research and experimental development from applying to “prospecting, exploring or drilling for, or producing, minerals, petroleum or natural gas”, the scope of the exclusion is not clear, and as such has created some confusion. It may be important to change the provision to support research into freshwater protection in fossil fuel production.

Fresh water resilience could also be supported with amendments to the capital cost allowance provisions in the Canadian tax law. There already exist deductions for expenditures on capital property relating to clean energy production. These classes do not specifically allow for deductions of water protecting properties but could be extended in this regard.

The Canadian tax system also provides environmental incentives through a unique Canadian Renewable and Conservation Expense provision, which allows for a ‘flow-through’ of qualifying expenditures from corporations to shareholders relating to clean energy production. This could also be extended to apply for water protection.

There are many opportunities within the Canadian tax system (and similar regimes in income tax systems of other jurisdictions) to provide the necessary incentives for freshwater protection. If designed with appropriate stakeholder input, and driven by guidelines and limits set by governments, based on scientifically researched data and long-range planning, the story of fresh water may in fact shift from one of uncertainty to one based on a theme of wisdom and carefully crafted guidance.

Recent Comments