Around the world, tax compliance is a serious problem with big consequences. The case is no different in Papua New Guinea (PNG). It is an important concern of the current Government. In July 2019, Prime Minister James Marape highlighted that there were outstanding tax payments of PGK2 billion (AUD840 million) due to poor compliance from businesses.

Last year, we partnered with the PNG Internal Revenue Commission (IRC) to test two new forms of tax-positive messaging in an attempt to improve tax compliance and government revenues. We sent SMSs to over 15,000 small and medium businesses before they were due to lodge their monthly salary and wages tax return, and the IRC included flyers detailing the shared benefits of tax (photo below) in letters and emails sent to non-compliant taxpayers.

IRC staff prepare a flyer to be sent to a non-compliant taxpayer (Photo credit: Chris Hoy)

IRC staff prepare a flyer to be sent to a non-compliant taxpayer (Photo credit: Chris Hoy)

This work is motivated by the application of behavioural insights and the success of similar interventions elsewhere. Behavioural insights (or ‘nudges’) seek to leverage an understanding of humans’ reliance on simple rules of thumb to shape their behaviour, often through small changes to how options are framed. Our trial was the first tax compliance study in a lower-middle-income country to send messages to all possible taxpayers. We randomised who received the messaging so we could compare the taxpaying behaviour of the individuals who received the messages with those who did not, and by doing so isolate the impact of the messages.

There were three key lessons we learnt – we discuss these in more detail in our new working paper.

1. The content of the messaging is not especially important

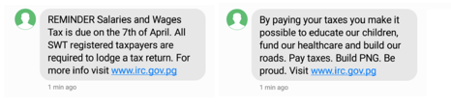

Before we developed the SMSs and flyers, we conducted a survey and focus groups for IRC staff and small business owners to understand local explanations for why compliance was so low and what types of messages may be most effective in making improvements. Respondents suggested that messaging that focused on simplifying the tax return process and highlighted the shared benefit of tax was expected to be most effective. Many said that messages that focused on social norms or the potential punishment for non-compliance would be perceived as not credible – this is consistent with the results of similar trials in other low-enforcement jurisdictions (for example, in Rwanda). For the SMS trial, we tested two messages (shown in the photo below), sending them to separate businesses. One was a simplifying reminder and the second one highlighted the shared benefit of taxation.

SMSs sent as part of the trial to improve tax compliance in PNG.

SMSs sent as part of the trial to improve tax compliance in PNG.

We were able to compare the relative effectiveness of the two SMSs. We saw that there was no significant difference in the effectiveness of the SMSs in improving compliance. Other studies have also observed similar effects from different messages (for example, in Ethiopia). This is likely because recipients treated the messages as an indication of engagement from the tax administrator (and the potential for follow-up) rather than focusing on the explicit content.

2. Those who are already engaged with the tax system and are exempt from paying tax are most likely to respond to messages

We were able to test how businesses with different taxpaying histories responded to the messaging. We could separate eligible businesses into three groups, those who had not filed a return for over 15 months (we call them ‘non-filers’, they made up 74 per cent of businesses eligible to receive an SMS), firms that had previously filed but claimed to be exempt from paying tax because they had no employees (‘zero filers’, 13 per cent) and firms that had previously filed and were paying tax (‘non-zero filers’, 13 per cent).

We found that previously filing taxpayers were much more likely to lodge their tax return if they received an SMS or a flyer than those who did not. This is likely because they were experienced with interacting with the tax system deciding whether to file or not was a more marginal decision, so they were more susceptible to a slight nudge.

Among previously filing firms, non-zero filers were hardly influenced. Whereas, zero filers were about twice as likely to lodge if they received an SMS than those who did not. Similar results also occurred with the flyers. This is understandable as zero filers only face the transactional cost of complying. In contrast, the non‑zero filers face the transactional and financial costs of complying, so they are less likely to be swayed.

We saw that the taxpayers that were most likely to respond to the SMSs and flyers are those that faced the lowest cost from compliance.

3. This compliance strategy will not fix PNG’s revenue problem

The COVID-19 crisis has compounded PNG’s revenue problem and the Government is now expecting a record budget deficit of over K6 billion (AUD2.5 billion) in 2020 due to an expected additional K2 billion (AUD840 million) hit to tax revenue. Unfortunately, while these interventions were able to improve the tax filing behaviour of some firms, they will not be able to address PNG’s revenue problem. There was a moderate (but statistically insignificant) increase in the amount of tax paid by those who received the SMSs, but it disappeared within a few months of businesses receiving the messaging. So did the compliance improvements. This contrasts with the success of similar interventions in other middle-income countries where significant revenue increases have been obtained (for example, in Guatemala).

There are two key factors that may have driven the failure of these messages to raise significant revenue in PNG. By sending the messages to a broader group of taxpayers than previous studies in low- and lower-middle-income countries, the messages would have been received by a significant share of businesses that are no longer actively operating. Secondly, according to some indicators compiled by the World Bank, PNG has weaker governance than other countries where these trials have been set (such as Rwanda, Ethiopia and Guatemala). This likely reduces the effectiveness of messaging received from the Government. Future research could explore whether differences in the ‘social contract’ between taxpayers and the Government could help to explain cross-country variation in the effectiveness of nudges in raising revenue.

Ultimately, this tax-positive messaging is not a silver bullet and the PNG Government will need to adopt other tools to realise Marape’s vision of ‘a time when all big corporations and all companies share the work load in paying tax and we can ease the burden on our small people paying huge tax out of their salaries.’ The Government and IRC are aware of this and have also been adopting more traditional methods to improve tax compliance. Appropriately, these measures place more emphasis on ensuring businesses pay the correct amount of tax rather than focusing on ensuring businesses are appropriately registered and are submitting returns. However, to further boost their effectiveness it may be worth testing incorporating data from third parties (such as banks, suppliers and clients) to personalise their messaging to non-compliant taxpayers. A study in Costa Rica saw a sizable increase in the total amount of taxes paid by non-filing firms for over two years after they received a nudge that showed the tax office was aware of specific economic activity of the firm, such as their total credit card sales reported by a credit card provider. However, as always, it should be kept in mind that not everything that works overseas works in PNG.

This blog has also been published on the Devpolicy blog, the blog of the Development Policy Centre at the Crawford School of Public Policy. You can read the TTPI working paper here.

Recent Comments