Budget 2016-17 recognised that more than $200 billion has been invested into liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects in the last decade. It has allocated funds for further exploration, in a $100 million investment into Geoscience Australia to spend on energy and groundwater potential in Australia.

The Geoscience ‘Exploring for the Future‘ program would produce pre-competitive geoscience data. The government’s investment will allow Geoscience Australia to undertake geological mapping of mineral deposits both near the surface and to depths down hundreds of metres.

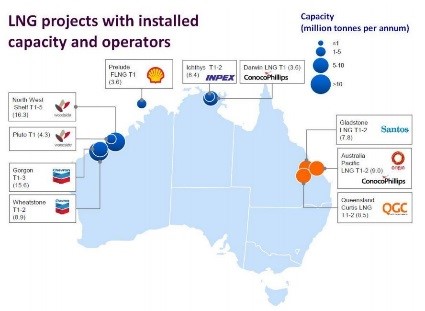

The investment is expected to underpin future exploration by private companies in remote and difficult to access areas. Geoscience Australia’s work was vital in the discovery of the Icthys natural gas field in 1996. The field’s operator, Inpex, is now exporting LNG. The image below shows large projects: natural gas to LNG in west and north, including Icthys; and coal seam gas to LNG in the east.

Source: Santos Ltd

The BEPS imperative

These large LNG projects commence in an era of record low oil prices. Government resource revenue has fallen due to prices rather than a paucity of projects. The tax base is also being eroded due to aggressive tax planning by oil and gas companies. Already Chevron, an oil major, has failed to defend its profit-shifting in the Australian courts: its loss has sent a message to industry. The OECD is making progress toward transparency, which requires multinational corporations to disclose tax information.

As part of increased transparency in tax systems, in 2011 Australia agreed to sign up to a pilot of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a program that provides a global standard for extractive industry companies to publish what they pay to governments (such resource rent taxes) and for governments to disclose what they receive. Australia’s EITI pilot had the objective of testing the practical application of EITI principles by demonstrating the effectiveness and transparency of our governance systems, financial systems and anti-corruption measures. The Australian pilot report was completed in May 2015 and it noted that payments from extractive industry and receipting agencies could be reconciled to a high degree of accuracy.

In the wake of the EITI pilot report, in May 2016 Julie Bishop and Josh Frydenberg issued a media release stating that Australia would become an EITI candidate. It is noted that Australia’s petroleum resource rent tax (PRRT) came under scrutiny in the pilot, and while industry payments could be reconciled to government receipts, there are still PRRT transparency issues that suggest the need for a different type of review.

PRRT and Transfer Pricing

Australia’s petroleum resource rent tax is profits-based tax, levied over a specified threshold, and generated from the sale of marketable petroleum commodities. The production of natural gas is subject to the PRRT, but not certain byproducts, such as LNG. To address gas taxation transparency, and perhaps improve the tax take, the first step is to review the current PRRT regulations on the gas transfer price methodology (GTPM) with the aim of determining whether it adequately covers the latest developments in natural gas extraction technology.

The GTPM is used to calculate the transfer price of gas feedstock for LNG processing. The price at the taxing point is a critical part of assessing a taxpayer’s liability for PRRT from upstream (natural gas extraction) activities. The large accounting firms interpret the GTPM for their clients’ integrated gas-to-liquids projects but the workings are not available for community scrutiny. How fair is the current GTPM process for potential resource investors into Australia, or the community as mineral rights owners via the state?

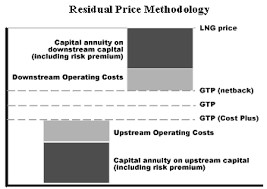

The GTPM is based on the transfer pricing approach known as the residual price method (RPM). This approach uses both netback and cost-plus to determine notional gas prices for upstream (natural gas extraction) and midstream activities (conversion to LNG). An unusual feature in the PRRT Regulations (2015) is for the difference in result from the netback and cost-plus approaches to be split 50/50 between upstream and midstream.

As price is a necessary factor to determine PRRT liability, a GTPM review is necessary given the number of LNG projects in Australia on the cusp of initial production. I am advocating for a GTPM review that would require liaison with the Australian Taxation Office and corporate tax units to prepare a comparison of the current myriad of GTPM interpretations as provided for in the PRRT Regulations.

I have just returned from a visit to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Extractives Industry group in Washington DC, where we discussed the issue of gas transfer pricing in the context of the low oil price shock. The IMF encounters this transfer pricing issue in their portfolio of developing countries that have integrated gas-to-liquids projects, but with no comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) for project sales gas. In these instances, the IMF reviews corporate interpretations of residual price calculations with an eye to potential tax leakage.

The PRRT gas transfer pricing methodology

The current PRRT Regulations (2015) preference the use of an Advance Pricing Agreement (APA) over the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method for gas pricing. If there is no APA or CUP, then next in the hierarchy is the residual price methodology (RPM) that uses the netback and cost-plus approaches. The diagram below illustrates the RPM provided for in the PRRT Regulations (2015) at sections 26 and 27.

Gas pricing hubs

Papers from the American Petroleum Institute’s Tax Forum in April 2016 skipped over the whole issue of gas transfer pricing methodologies. This is because the United States has a well-developed gas extraction industry that sends production gas to ‘collector’ facilities. These facilities use gas pricing from the Henry Hub, a pipeline interchange in Louisiana, where a number interstate and intrastate pipelines interconnect through a header system. The hub sets the benchmark gas price, and it is used for royalty calculations. There is no such hub in the Asia-Pacific region, although much has been written about the need for one and possible sites. Large LNG projects just underway in Australia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea may stimulate efforts to establish a regional hub. Such a hub would be also useful for CUP purposes and obviate the need for contentious GTPM calculations.

Recent advances in LNG technology, such as integrated offshore floating facilities – termed FLNGs – point to the need for a review of the GTPM methodology. FLNG is new and unproven technology. Thus when a GTPM is performed, factors are input relating to the risk premium – that are largely untested. A 2014 report by a bipartisan committee drawn from the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia has urged the Commonwealth Government to re-examine the tax treatment of the development costs of FLNG and the valuation of the vessel, as the PRRT was designed and implemented prior to the development of FLNG technology. I agree with the call to review.

Recent Comments