With unemployment low and commodity prices favourable, the federal budget would already be in balance under prudent budget management, but that has been lacking for some time. Instead, a budget deficit of 1.5 per cent of GDP is expected in 2025-26. This budget deficit is structural, not cyclical, and so it will not vanish naturally. Repair work is therefore needed.

The 2025-26 Budget, in its Table 1.2, forecasts that it will take until 2035-36, 11 years into the future, to get the budget back into balance. This slow budget repair work is done by that old friend of governments, bracket creep. As the budget acknowledges in its Chart 1.1, the government only returns two out of the next eleven years of bracket creep for the average wage earner. The nine years of unreturned bracket creep raise the average tax rate for a worker on average earnings from 20.3 per cent in 2024-25 to 23.6 per cent in 2035-36.

This represents a hefty 16 per cent increase in the tax burden for that average worker, relative to a situation where the average tax rate is kept constant by adjusting tax brackets in line with growth in nominal incomes. This hefty tax increase will impair incentives to work and save. Brazenly, in its Box 1.2, the budget estimates positive incentive effects from returning two years of bracket creep, without mentioning the negative incentive effects from the eleven years of bracket creep itself.

The interests of ordinary Australians would be better served if the budget is balanced by relying less on bracket creep, which is regressive, and more on economic reform. Possible reforms include finding efficiencies in government, relying more on efficient indirect taxes, and expanding tax bases using productivity-enhancing reforms.

Assessing the budget’s economic parameter forecasts

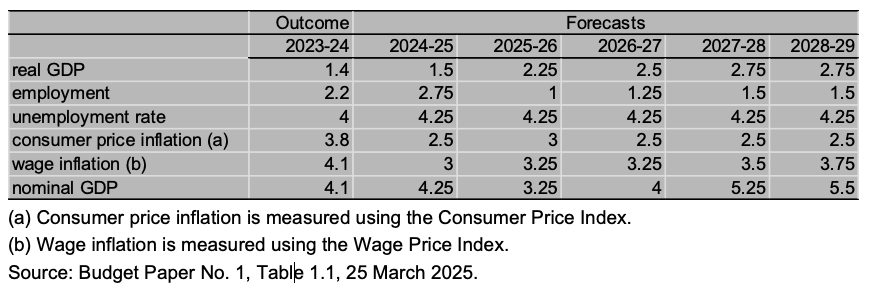

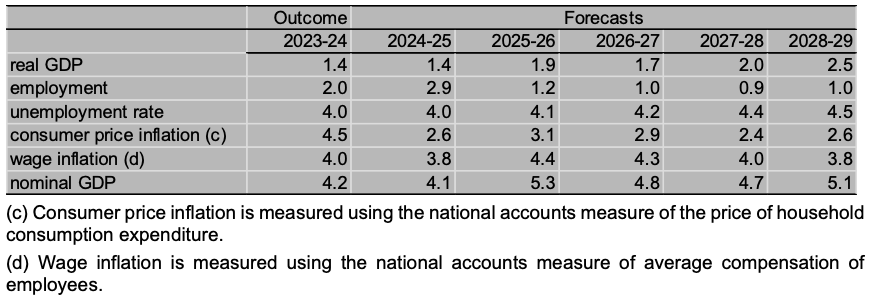

Putting aside the bad policy choice regarding the method of budget repair, the question remains whether the budget projection of a balanced budget by 2035-36 is plausible. That depends in part on whether the budget’s economic parameters are plausible. The budget’s key medium-range economic forecasts are in Table 1 below, and my own macro-econometric model forecasts are in Table 2 for comparison.

Table 1: Budget forecasts of major economic parameters

In the short term, the budget’s economic forecasts with a bearing on the budget balance are pessimistic. The budget predicts relatively low growth in nominal GDP in 2025-26 and 2026-27 of 3.25 and 4 per cent respectively (Table 1), against my forecasts of 5.3 and 4.8 per cent (Table 2).

The main reason for the difference between these forecasts is that the budget follows its usual practice of making pessimistic forecasts for commodity prices, with both iron ore and coal prices assumed to fall markedly over the next 12 months. This leads to pessimistic short-term forecasts for growth in tax revenue. Indeed, the Treasury makes deliberately pessimistic forecasts for commodity prices to reduce the risk of government over-spending, given that the outlook for commodity prices is always quite uncertain.

Table 2: My forecasts of major economic parameters

In the medium term, the budget forecasts are more optimistic. Over the next four years, the 2025-26 Budget predicts that real GDP will grow at an average annual rate of about 2.5 per cent compared to my forecast of 2.0 per cent, adding an extra 2 per cent to the level of real GDP by 2028-29.

One reason for this difference in forecasts is that the budget predicts a sharp turnaround in labour productivity growth from the negative rate of recent years to a normal positive rate from 2025-26 onwards, whereas my model forecasts that the turnaround will be more gradual. Another reason is that the budget predicts that unemployment can be maintained at 4.25 per cent, whereas I forecast a gradual rise towards an estimated sustainable rate of 4.7 per cent (Table 2), sapping economic growth for the period shown in Table 2.

The budget does not provide economic forecasts for the remaining seven years to 2035-36. However, the economic projections in the 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR) may provide a guide. The differences between my economic forecasts and the IGR economic forecasts for this more distant period are relatively minor.

On that basis, by 2035-36, it appears likely that, compared to my forecasts, the budget forecasts are likely to be about 10 per cent lower for the terms-of-trade, primarily due to pessimistic commodity price predictions. Conversely, they are about 2 per cent higher for real GDP, driven by an optimistic labour productivity and unemployment outlook. These two differences would have broadly offsetting effects on the budget balance.

Thus, the budget projection for a balanced budget in 2035-36 seems reasonable. Of course, there is a wide band of uncertainty around long-range budget forecasts. Further, fiscal policy will undoubtedly change over the next eleven years. Let us hope that it does, so the budget is balanced making more use of better methods than bracket creep.

Recent Comments