We ought to think of the tango when we think of social welfare. In a well-crafted social welfare system, taxes and public transfers tango with grace and precision, maintaining harmony between equity and efficiency. It takes two to tango, when one partner steps backwards the other steps forwards in sync. A new transfer without its tax counterpart is like pushing someone solo onto the dance floor.

Cue the current proposal that gives every Tom, Omar, and Gina $300 in energy bill credits, regardless of their income (and some might get multiple if they have a holiday house or secondary residence). The government says a universal discount is the “simplest” way, and it could not have been means tested.

To the government’s credit, a universal roll out brings much needed relief quickly (whether it would contribute to winning an election or reducing inflation is another matter). And there is no denying that there are hurdles to restricting the discounts below a certain income. There are costs and data sharing hurdles as the government rightly puts.

But there is no need for the energy relief to dance solo when it can gracefully tango with tax.

What can be done when a transfer can only be universal?

There is nothing wrong with a universal subsidy if it is complemented by a highly progressive tax.

There is an optimally negative relationship between transfers and income tax progressivity. In the Australian context, Chung Tran and I recently showed that if income tax becomes less progressive, the age pension needs to be highly targeted towards low incomes. On the other hand, if pensions were to become universal, it needs to be financed with more progressive income tax in order to maintain the balance between equity and efficiency.

This last conclusion is of relevance when it comes to the universal energy relief. There is scope to make it more equitable and efficient (in terms of reducing wasteful expenditure) if it were to be paired with a progressive energy relief levy.

I am not an expert in tax design, and I do not have the time or the money. And importantly I do not want to bore you. So I shall leave it to the experts to iron out the details. But I can show one small example of how such a levy could work.

Example: an energy levy of 0.5% on incomes above $135,000

Temporary levies have always been a part of the Australian tax system. The temporary budget repair levy of 2014-15 that levied two per cent for each additional dollar over $180,000 is the most recent example. Let us consider a smaller levy of 0.5% but imposed at a lower threshold of $135,000. There is no academic reason for this threshold. Just a rudimentary value judgement that an individual with that amount of income probably does not require the full subsidy.

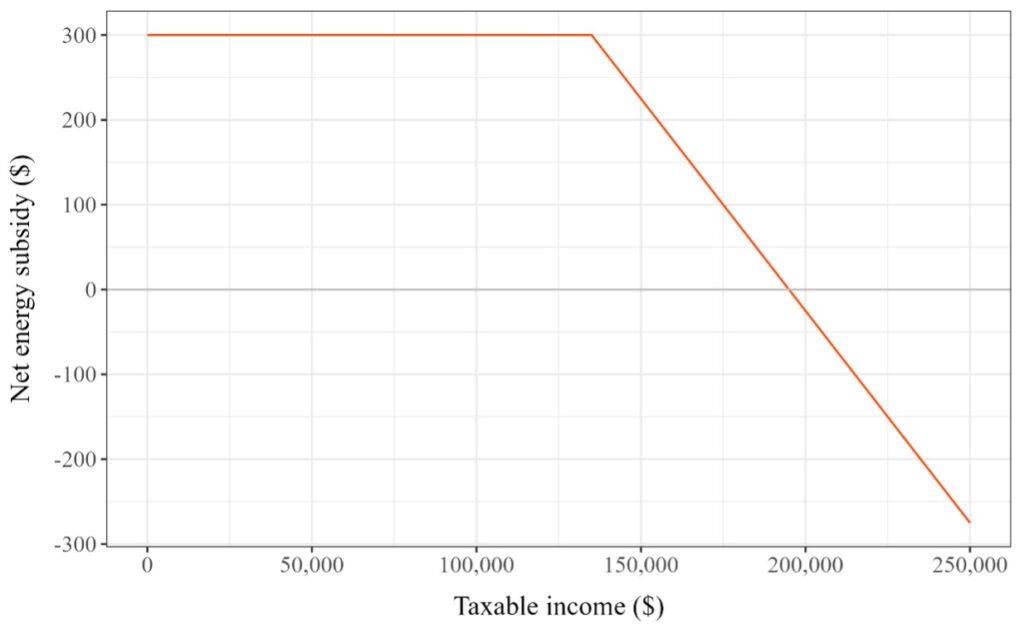

Figure 1: Net energy subsidy (0.5% levy)

Such a levy in effect introduces a taper rate for the energy subsidy, making it means-tested by proxy. As shown in Figure 1, if the levy is 0.5%, the “net” subsidy will be completely phased out by $195,000 (slightly above the 2024-25 top threshold for income tax).

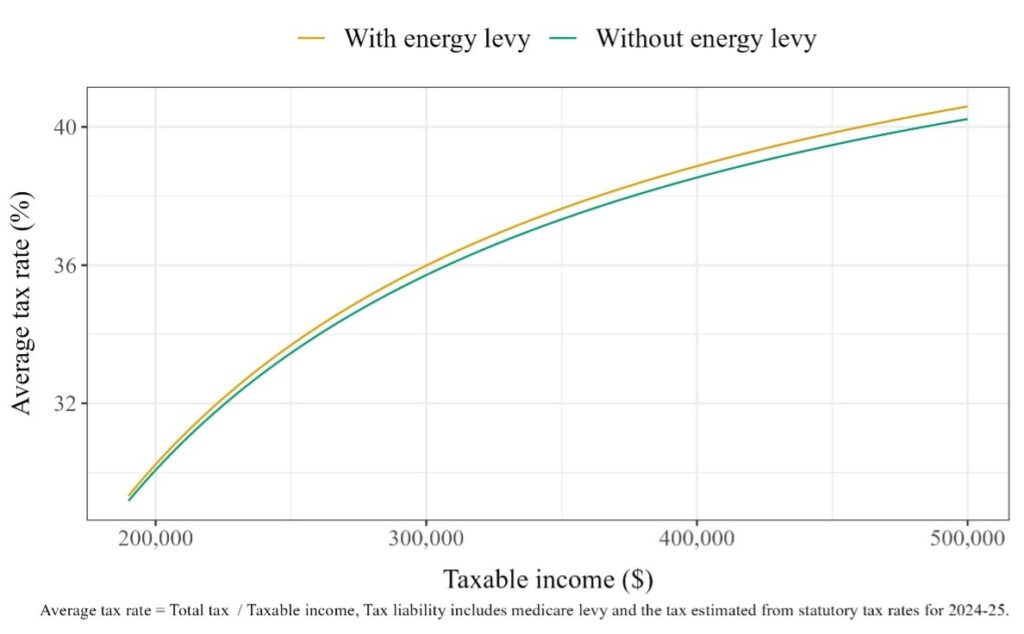

Effectively, those in the top threshold finances the subsidy for those below. Importantly, at a meagre rate of 0.5% the levy would only increase the tax burdens at the top by a few percentage points (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average tax rates above the top threshold with and without the energy levy

It is not my intention to provide a full costing and revenue breakdown for this subsidy and levy combo. But it is not a stretch to posit that a significant portion of the costs of the energy subsidy could be recouped by such a levy. For instance, applying the 0.5% energy relief levy on the ALife 2020 sample (the most recent available) yields a total revenue of around $66 million – and that is only a 10% sample of tax filers.

A simple solution

There is scope to design an even better and more targeted levy that recovers the full cost of the energy relief subsidy. The Australian Taxation Office and Treasury both have the skills and capacity to access and use high quality income and demographic data to design an effective levy (even if energy retailers do not have the same).

What I have proposed in this note is just a simple example to highlight an important point – a universal subsidy can (and perhaps should) be accompanied by a progressive levy that remedies any concern about equity.

Why have an energy subsidy at all?

It makes me laugh when Governments, egged on by rapacious and economically ignorant Treasuries, have destroyed the traditional Australian land rates funding system for infrastructure networks which benefit landholders. The optimal pricing structure for utilities was, and is, flow metered at marginal cost with fixed costs met by charges on the value of the lands serviced. Sir Joseph Carruthers in NSW in 1906 anticipated the Hotelling optimal pricing rule in the 1930s.

You can’t understand optimal utility pricing till you remember there are three factors of production, not two, that Y=F(K,L) is JB Clark nonsense and that land values reflect and soak up all beneficial externalities of infrastructure availability to service land.

Treasuries and Productivity Commissions created rapacious corporatised or privatised utilities pricing at average cost on inflated asset values. Governments loved selling off these monopolies as much as the French monarchy loved selling off the salt tax to tax farmers in the 18th century.

No wonder the peasants are revolting.