As Sven Steinmo states in his book Taxation and democracy, “Governments need money. Modern governments need lots of money.” This is no less true today than it was twenty-five years ago when he wrote it. In fact, countries face many new challenges that require increasing amounts of money. Yet, not all countries are equally efficient at collecting taxes. Scholars have put forth many possible reasons for this, but culture and institutions are usually referred to as the main culprits.

In my recent study published in the Journal of Public Policy, titled “More bang for your buck: Tax compliance in the United States and Italy”, I investigate this puzzle. Are Italians less willing to pay taxes than Americans, because of something inherent to Italian culture (see Banfield and Putnam et al.)? For instance, Alan Greenspan once said in the Financial Times, “The Eurozone is confronted with a crisis of not just labour costs and prices – but culture.” This was clearly a critique of Southern European culture. Or are Italians less willing to pay taxes to specific public institutions because the quality of their institutions is low?

The experiment

In 2016, a team of researchers and myself at the European University Institute in Florence set out to examine if some cultures are more averse to taxation, or if institutions are driving differences in behaviour. By conducting the same exact test in each country, we held the institutions constant, while varying culture. For our study, we invited approximately 700 individuals (mainly students) in the United States and Italy to take part in an experiment in a computer-based laboratory. We asked them to perform a basic clerical task: Copy a line of text from a piece of paper to a spreadsheet on the computer. For each row copied correctly, they received 10 currency units. At the end of the experiment this was converted into real money.

After each clerical task, we presented students with a tax scenario and asked them to report their income based on their earnings from the clerical task. There were four clerical tasks. After each clerical task, subjects were confronted with six unique tax scenarios. Thus, there was a total of four clerical tasks and six reporting rounds.

The scenarios ranged broadly. In round one, participants paid taxes for no other reason than for the fact that we asked them to report their taxes. In rounds two and three, all of the tax revenue was put in a general fund and redistributed. Specifically, in round two all tax money was redistributed equally, while in round 3 low-earners received a bit more from the pot than everyone else. For rounds four through six, we adjusted the institution to which they paid, so the taxes went to their federal government, pension system, and fire department. We donated the money to these institutions after the experiment. Therefore, Italians were given the exact same decision as Americans in rounds 1-3, and country-specific decisions in rounds 4-6. This was then followed by a short ten-minute survey.

Students could report however much of their income they wanted. Although we did not state this explicitly, it can be assumed that students understood that they would keep more money if they chose not to report all their earnings, just as is true with actual taxpayers.

Finally, we told them there was a 5 percent probability of being audited. If we caught them cheating, they would have to pay a fine equal to twice the taxes owed. With such a small chance of being audited and a rather small fine, from a rational choice perspective, the best choice would always be to report no income. (We have used a similar approach for other experiments, as you can see in a previous Monkey Cage post).

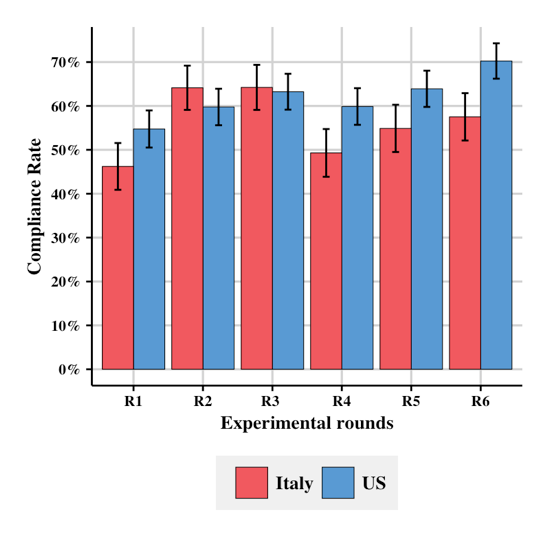

Figure 1: Compliance rate by country

Tax evasion: is it cultural or because of institutions?

As can be seen in Figure 1, Italians do not seem to be less willing to pay taxes when the institutions/incentives are the same. Indeed, when their money is put in a pot and shared equally among everyone in the room in round two, Italians increase their compliance significantly more than Americans. This implies that Italians are significantly more responsive to redistribution than Americans.

However, a different story emerges when we ask Italians to pay taxes to their real public institutions. Italians are more likely to be significantly less compliant than Americans when contributing to the national government in round four, and to the fire department in round six. Interestingly, the effect in round six is by far the largest, which arguably demonstrates the positive public perception of the fire department in the United States.

The fact that Italians seem just as willing to pay taxes to abstract institutions as Americans, but are less willing to pay taxes when that money goes to their real public institutions, implies that Italians are not actually less honest, or less willing to pay taxes than others. In fact, they are very much willing to contribute to the public good when the money is distributed among their peers. However, they are significantly less inclined to share with the state. Rather than something engrained within some civic cultures, it is plausible that the problem of tax evasion stems from low institutional quality, which feeds distrust, and that distrust in turn reduces tax compliance.

Improving compliance

Institutions are sticky. Over time, they generate norms and behaviours that become hard-wired into society. Tax compliance can thus be seen as a product of how a particular set of institutions evolved over time (see also Sven Steinmo’s The Leap of Faith for great examples from five countries).

By examining the coevolution of state and society, researchers and policymakers can get a good glimpse into why governments face tax compliance environments that are highly specific to the country. There are ways in which governments can improve these issues of compliance. Increasing transparency, reducing corruption, and increasing the accountability of tax administrations are the obvious examples. But in the short term, countries have implemented measures, such as tax education and budget tools, with some success.

Recent Comments