Several governments around the world have recently passed measures to increase tax transparency. For instance, the UK now requires large firms to publish the firm’s tax strategy annually, while the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) framework calls for multinational firms to file country by country tax reports with the firm’s local tax authority.

In Australia, the tax authority now publicly discloses three ‘line items’ of large corporations’ tax returns: total income (a measure of revenue), taxable income, and income taxes payable. The mandate affects public Australian, and public and private foreign corporations with at least AUD100 million of total income, and private Australian corporations with at least AUD200 million of total income.

Because publicly disclosed tax return data is limited to three line items, it is very hard for the public to learn much if anything about firm behaviour. In fact, on its website, the Australian Tax Office (ATO) concedes the limitations of the disclosed tax return data and points out that some entities may choose to provide additional information on their own. Firms will voluntarily disclose additional information if they believe that the benefit of doing so exceeds the cost. In this case, the mandated partial tax return disclosure may increase the benefit of a more complete voluntary disclosure if a firm believes that the public will incorrectly perceive the firm’s partial tax return statistics.

For instance, if the ATO’s partial tax return disclosure reveals that the extent of a firm’s tax planning exceeds stakeholders’ expectations, stakeholders may be more likely to expect that the firm is engaging in aggressive behavior that stretches the boundaries of what the law intends. However, a firm can also reduce its tax liability by following both the spirit and the letter of the law. Firms that engage in non-aggressive tax planning have an incentive to avoid reputational costs by explaining their practices to distinguish themselves from firms that engage in aggressive tax avoidance.

To explore this hypothesis, I searched websites, stock exchange disclosures, and annual reports of publicly listed Australian firms for voluntary disclosures that specifically reference and supplement the ATO’s partial tax return disclosure. For the data collection, I focused specifically on public Australian firms as these firms are most likely to garner local media attention which could generate reputational concerns.

One in ten firms disclosed supplemental information voluntarily

I find that 40 of the 363 unique parent companies in my sample – approximately 11 per cent – issue supplemental tax disclosures in the period surrounding the first two years of the ATO’s disclosures. The contents of the disclosures suggest that they aim to curb reputational costs.

For instance, 84 per cent of the supplemental disclosures reconcile the firm’s Australian taxable income to its Australian tax payable to explain how the firm is fairly and legally paying less than the 30 per cent statutory rate. The most common explanation, provided in 66 per cent of the reconciliations between Australian taxable income and tax payable, is the use of a research and development (R&D) tax credit. Firms likely provided this information to assure stakeholders that they are following the law and (hopefully) providing a benefit to society since R&D tax credits relate to firm innovation which should help grow the economy and benefit society.

The second most common reconciliation, provided in 63 per cent of voluntary disclosures, is a reconciliation between the firm’s financial accounting net income and its tax return taxable income. Firms likely provided this reconciliation to assure stakeholders that the firm is neither artificially inflating its financial accounting net income nor artificially deflating its tax return taxable income.

It is an interesting indirect result that mandated partial tax return disclosures led to voluntarily issued more complete tax disclosures. One of the stated objectives of Australia’s tax transparency legislation was “to provide more information to inform public debate about tax policy”. Although the mandated disclosures themselves are too limited to inform public debate, the additional information provided by the voluntary disclosures allows the public to gain some insight into the types of tax planning firms engage which could lead to more discussion of Australia’s tax policies.

Firms concerned with reputational backlash are more likely to disclose information

After collecting data on disclosures, I used a Probit regression to test which firms are most likely to voluntarily issue supplemental information that either preempts or is issued at the same time as the ATO’s first tax return disclosure. I find that firms with an unexpectedly low Australian tax payable are more likely to voluntarily issue supplemental information.

Specifically, firms which have no Australian tax payable and have not previously disclosed that the firm does not owe any taxes in Australia (the firm’s worldwide current tax expense reported on its publicly available income statement is positive and not broken down by country) are 25 percentage points more likely to issue supplemental information. These firms are likely to expect the largest reputational costs from the ATO’s disclosures given the Australian media’s heavy focus on firms that “paid no tax”.

However, when a firm’s lack of Australian tax liability does not come as a surprise (the firm’s previously disclosed worldwide current tax expense is zero or negative), the firm does not appear to expect the saliency of the ATO’s disclosure to lead to new reputational costs and is 11 percentage points less likely to issue a supplemental disclosure.

My Probit regression also shows that firms with R&D expenses, which I use as a proxy for firms that are most likely to claim an R&D tax credit, are 19 percentage points more likely to issue a preemptive or concurrent voluntary disclosure. In line with the analysis above, these firms likely engage in non-aggressive tax planning and hope to distinguish themselves from firms who engage in aggressive tax planning.

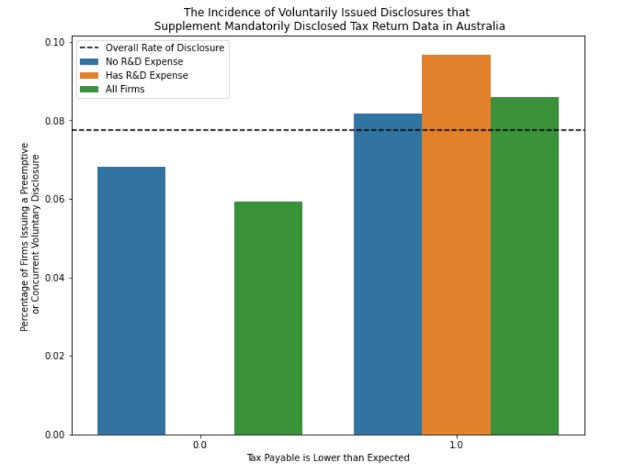

The figure below reiterates these results and shows that overall, firms whose Australian tax payable is lower than what one would expect based on the firm’s financial statement disclosures are more likely to issue a voluntary disclosure to explain this discrepancy. This result is strongest for firms with R&D expenses (firms most likely to claim an R&D tax credit), which supports the hypothesis that firms issued voluntary disclosures to better explain their tax positions if the firm expected such tax positions to be supported by the public.

What we can learn

To conclude, I believe that my results provide evidence that firms are willing to voluntarily provide additional information that supplements mandated disclosures so as to remain in control of their disclosure environment. Governments around the world are considering mandating both more tax disclosures and more corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosures. I believe that my results speak to both legislative decisions. Specifically, my results suggest that if a firm believes a mandatory disclosure incorrectly portrays the firm’s true economic positions, the firm is likely to issue supplemental information to clarify. As such, the firm remains in control of its overall disclosure environment.

Journal article

Kays, A. 2022. Voluntary Disclosure Responses to Mandated Disclosure: Evidence from Australian Corporate Tax Transparency. The Accounting Review, 97 (4): 317 – 344.

Recent Comments