Australia’s fertility rate has dropped to a historic low of about 1.5 births per woman – well below the replacement level of 2.1. At the same time, Australia’s population is aging, putting growing pressure on the sustainability of its retirement systems.

In response, the Australian government has gradually increased the Age Pension eligibility age for women from 60 to 67. This reform was intended to encourage older Australians to remain in the workforce longer and to ease fiscal pressures associated with an aging society. However, a significant – but often overlooked – consequence of this policy is its intergenerational impact.

One such impact is the reduced availability of grandparents, particularly grandmothers, for childcare – an important factor that can influence fertility decisions. In our recent paper published in Economics Letters, we explored this intergenerational trade-off.

We find that increasing the pension age reduced the availability of grandmothers to provide childcare, leading daughters to have fewer children and to delay or forgo childbearing altogether. Specifically, having a grandmother eligible for the pension increased a daughter’s likelihood of having a child from 69% to 73.5%, and raised the average number of children per woman from 1.47 to 1.56.

These insights highlight the need for policymakers to carefully balance the demands of an aging population with the support required by younger generations.

The role of grandparents in childcare

For many Australian families, grandparents play a crucial role in providing informal childcare.

As illustrated in Figure 1, Census data show that the proportion of women caring for other people’s children, most likely their grandchildren, increases steadily with age and peaks around the Age Pension eligibility age. In other words, as women transition into retirement, many step in as caregivers, supporting their adult children in managing work and family responsibilities.

This support carries real economic value. It helps reduce childcare costs and enables higher workforce participation among parents. A recent Productivity Commission report noted that caring for grandchildren often leads grandparents, predominantly grandmothers, to reduce their own work hours. In effect, the availability of “free” childcare from grandparents can significantly ease both the logistical and financial challenges of raising children.

While policymakers have long recognised the benefits of this support, less attention has been given to the flip side: when policy changes encourage older Australians to work longer, what happens to the families that rely on their care?

Figure 1: The share of women providing care for other people’s children

Pension reform as a natural experiment

Australia’s gradual increase in the Age Pension age provided a natural experiment to study this question.

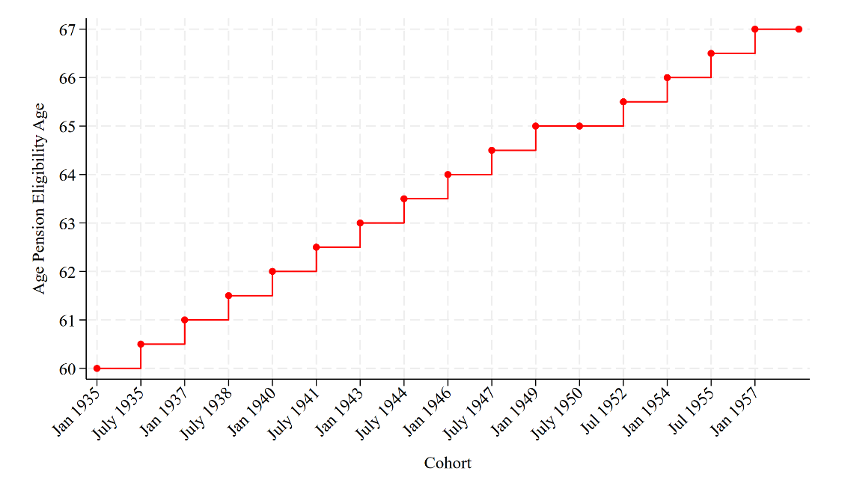

The reform was implemented incrementally based on birth cohorts. For example, women born just before a certain cutoff date were eligible to claim the Age Pension at 60, while those born just after had to wait until 60.5 (see Figure 2). This created a situation in which two otherwise similar grandmothers close in age faced different retirement incentives solely due to the timing of the policy change.

We exploited this scenario using nationally representative panel data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. By comparing daughters whose mothers qualified for the Age Pension with those whose mothers missed the eligibility threshold, we were able to isolate the effect of pension eligibility on fertility decisions. Our analysis controlled for a range of factors, including age, education, and time-invariant individual characteristics, ensuring that the observed differences are attributable to the policy-induced shift in grandmothers’ retirement timing. This approach accounts for underlying trends and cohort differences, allowing us to identify the causal effect of the policy-driven delay in grandmothers’ retirement.

Figure 2: Age pension eligibility age for women by birth cohort

Key findings

Our research reveals a clear intergenerational link between pension policy and family outcomes. In summary:

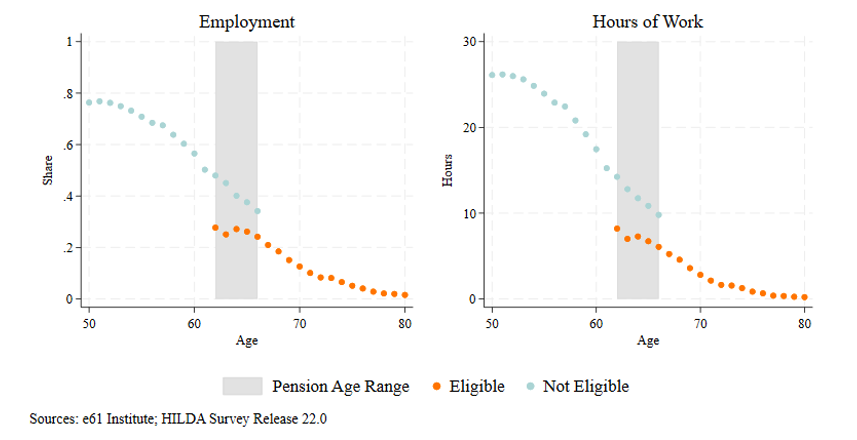

- Delayed retirement among grandmothers: Raising the pension eligibility age proved effective in extending older women’s participation in the workforce. After controlling for other factors, only about 25% of grandmothers who were eligible for the Age Pension remained employed, compared to 36% of those who were not yet eligible – a substantial drop in labour market participation. On average, ineligible grandmothers – those required to wait longer for the pension – worked 3.9 hours more per week than their eligible counterparts (see Figure 3). In essence, the reform led many grandmothers to delay retirement and stay in the workforce longer, achieving its objective of increasing employment among older Australians.

Figure 3: The effect of Age Pension on women’s labour market outcomes

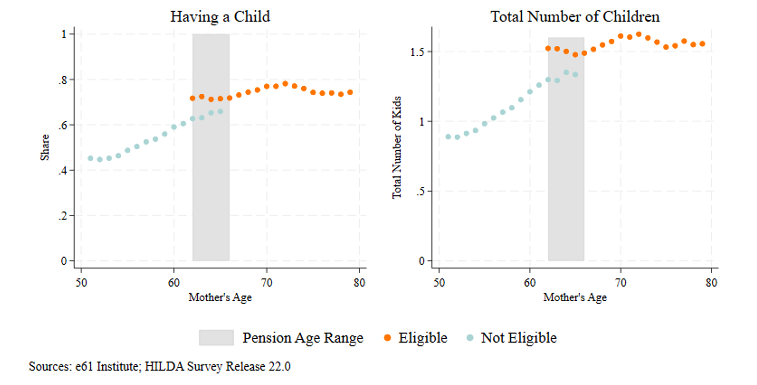

- Reduced fertility among daughters: A consequence of grandmothers working longer is a reduction in the informal childcare support available to their daughters. The study finds that women whose mothers were eligible for the Age Pension – and therefore more likely to retire – had higher fertility than similar women whose mothers were not yet eligible. Specifically, having a pension-eligible mother increased the likelihood of a daughter having a baby from about 69% to 73.5%. Similarly, the average number of children per daughter was higher when the grandmother could retire: 1.56 compared to 1.47 among those whose mothers were still below the pension age threshold. This 4.5% increase in fertility is quite substantial – comparable to the rise in birth rates observed following the introduction of Australia’s paid parental leave scheme.

Figure 4: The effect of mother’s Age Pension eligibility on daughters’ fertility

- Uneven impact – hardest on low-income families: The fertility effects of the reform were not felt equally across all households. Daughters from lower-wealth families or with less education experienced the strongest effects. In these groups, grandmothers’ eligibility for the Age Pension had a greater influence on both the likelihood of having a child and the number of children born. In contrast, families with higher incomes or more education – who may have better access to formal childcare or other support systems – were less affected by the change. This suggests that the financial and caregiving support provided by grandmothers plays a particularly important role for families with fewer resources.

- The childcare trade-off: The underlying mechanism behind these fertility effects is relatively straightforward: grandmothers who remain in the workforce have less time to care for their grandchildren. The data support this, showing that pension-eligible grandmothers are more likely to provide childcare, while those still working – often longer hours – are less available. By raising the pension age, the reform effectively delayed many women’s ability to step into caregiving roles. For their daughters, the loss of informal childcare increases the costs – whether in time or money – of having additional children. This added burden can lead some women to postpone childbearing or forgo it altogether. While fertility decisions are influenced by many factors, this study highlights that access to grandparental childcare is a key piece of the puzzle. As expected, when this support system weakens, it can shift the balance against having a (or another) child.

- Grandfathers, fathers, and sons: The study also examines whether similar patterns emerge for grandfathers and their sons. While pension eligibility reduced labour force participation among grandfathers, it did not result in a significant increase in their involvement in childcare. Likewise, grandmothers’ pension eligibility had only a small and statistically insignificant effect on their sons’ fertility decisions. Fathers’ pension eligibility also showed only marginal influence on their daughters’ fertility choices. These findings reinforce the idea that grandmothers play a uniquely important role in providing intergenerational childcare support, with direct consequences for their daughters’ fertility decisions.

The findings reveal a clear trade-off between extending workforce participation at older ages and supporting fertility outcomes. While increasing the pension age successfully extended working lives, it also had unintended consequences for birth rates. In the context of Australia’s already historically low fertility rate, even small declines could have long-term demographic implications. The study underscores the complex interactions between retirement policy and family outcomes, particularly in societies where informal childcare plays a key role.

Further reading

Akyol, P., & Atalay, K. (2025). The intergenerational impact of pension reforms: How grandmothers’ pension eligibility affects daughters’ fertility. Economics Letters, 248, 112239.

Akyol, P., & Atalay, K. (2025). Intergenerational impacts of pension reforms on fertility. e61 Institute.

Recent Comments