The Australian Budget 2025-26 announced reforms aimed at enhancing labour market competition and productivity. One of the key changes is the ban on non-compete clauses for low- and middle-income workers. Specifically, employers will no longer be able to enforce non-compete clauses on employees and contractors earning under $175,000 per year from 2027.

What are non-compete clauses? What are their pros and cons?

Non-compete clauses (NCCs) are contracts between employers and employees that prohibit the practice of a trade or profession for a specified time and within a specified region after termination of employment. These clauses are intended to protect employers’ proprietary information and investments in employee training. However, their impact on labour market dynamics and macroeconomic performance is a subject of debate.

NCCs offer several advantages for businesses. They help protect trade secrets and confidential information, ensuring that sensitive data such as proprietary processes and client lists are not used by competitors. They may encourage firms to invest more in employee training, knowing that their investment is less likely to benefit a rival company. Additionally, they can help retain key talent, reducing turnover and the associated costs of hiring and training new employees.

Research indicates that NCCs can encourage firms to invest more in training their employees but may discourage employees from investing in their own human capital. Studies have also found that although NCCs can boost firm-specific investments and productivity, they may reduce overall labour market mobility and innovation, potentially causing negative broader economic impacts.

NCCs limit employee mobility, potentially leading to lower wages, reduced career advancement opportunities, and skill mismatches. Additionally, NCCs can stifle industry-wide innovation and knowledge sharing as employees miss out on valuable learning experiences at more innovative companies, or are unable to share their expertise with other firms. Enforcing NCCs can also be costly and time-consuming, involving legal disputes and potential litigation.

How common are NCCs in Australia? What is the evidence on their impact?

NCCs first appeared in Australian employment contracts in the early 20th century, mainly in high-wage and senior roles. By the late 20th century, their use expanded to middle management and specialised technical positions, becoming common in industries like technology, finance, and professional services.

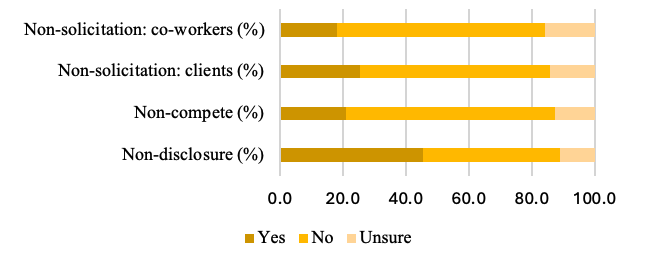

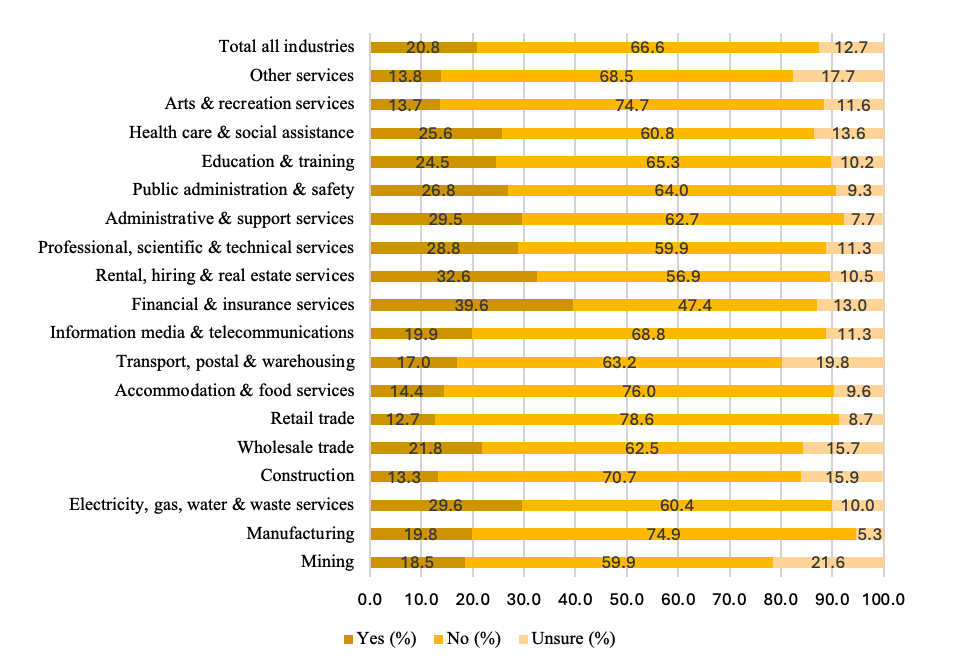

The 2023 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Restraint Clauses Survey provided insights into the current prevalence and types of restraint clauses used by Australian businesses. It revealed that 21% of businesses used NCCs for at least some of their employees in 2023 (Figure 1). These clauses were prevalent across various sectors, affecting both high-wage and low-wage roles, including fast-food workers, childcare providers, and security guards (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Restraint clause use by employers

Figure 2: Use of NCCs by industry

Using the 2023 ABS survey data linked to employer-employee microdata, recent e61 research found that increased use of NCCs was associated with reduced job mobility and lower wage growth, particularly for low-skill workers. Specifically, workers at firms that increased their use of NCCs experienced an 11% decline in job-separation probability and a 10% decline in job-to-job transition probability, with a notable 29% fall in within-industry transitions. Importantly, workers at these firms were paid 4% less on average than those at firms using only non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), with lower-skill workers seeing around a 10% lower wage level after five years of tenure.

NCCs: An additional economic barrier for low-wage workers

NCCs are particularly challenging for low-wage workers because they limit job mobility and restrict opportunities for better employment, trapping workers in low-paying jobs. These workers often lack the bargaining power to negotiate better terms and the financial resources to contest these clauses legally. As a result, they can face prolonged periods of unemployment or underemployment if they cannot find new jobs within their industry.

Evidence on the impact of the 2008 Oregon ban on non-compete agreements for hourly-paid employees revealed a 2-3% increase in hourly wages on average, improved job mobility, and better occupational status. The positive effects were especially significant for female workers and those in occupations where NCCs were common. These findings underline the need for policy reforms aimed at restricting the use of NCCs, especially in low-wage sectors.

A recent Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper proposes several measures to reduce the negative impact of NCCs on low-wage workers in Australia. These include banning or limiting NCCs for low-wage jobs by setting a minimum salary threshold, requiring employers to clearly explain NCC terms, and providing legal support to help workers challenge unfair NCCs. Overall, it calls for stronger government intervention and legislative changes to protect these workers and enhance their bargaining power.

Why aren’t workers compensated for agreeing to NCCs?

The theory of compensating wage differentials suggests that jobs with undesirable characteristics must offer higher wages to attract workers. Applied to NCCs, this implies that workers should receive higher wages to compensate for restricted job mobility. However, in practice, this compensation is often not provided, especially for low-wage workers with less bargaining power.

Recent research examines how compensation for NCCs varies based on an employee’s position within a firm’s hierarchy. Employees in top positions often receive high compensation, including wages and benefits, to offset the restrictions imposed by NCCs, as their departure could significantly impact the firm. NCCs are usually absent in middle positions to incentivise effort. Surprisingly, NCCs reappear at the bottom of the hierarchy, where employees receive minimal compensation due to their limited bargaining power and lower perceived risk to the firm. The study finds that prohibiting NCCs for bottom positions could enhance social welfare.

A step in the right direction

While NCCs can protect trade secrets and encourage investment in employee training, they also pose significant barriers to job mobility and wage growth, particularly for low-wage workers. Evidence suggests that NCCs often limit career advancement and suppress wages, exacerbating economic vulnerability for those in lower-skilled positions. Regulatory interventions, such as limiting the duration of NCCs, requiring compensation for affected employees, and banning their use for low-wage jobs, are crucial steps towards balancing the protection of business interests with the need to enhance worker mobility and innovation. The proposed ban on NCCs for low-income workers seems a step in the right direction.

Recent Comments