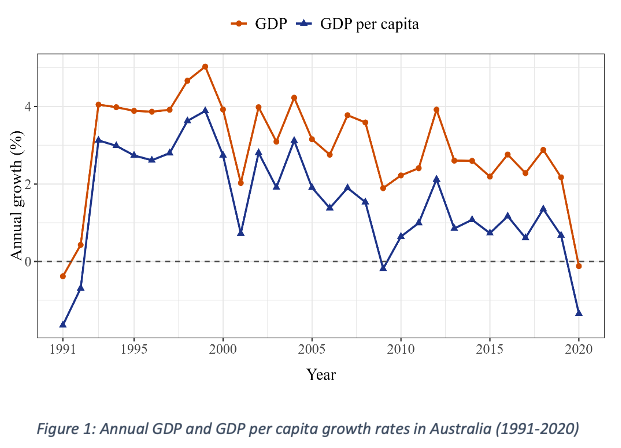

From the 1990-91 recession to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Australia enjoyed one of the longest periods of uninterrupted economic growth in modern history (see Figure 1). Unlike most advanced economies, Australia avoided major recessions, making this three-decade boom a truly remarkable achievement.

However, beneath the headline numbers lies a critical question: How evenly were the benefits of this growth distributed? Did it result in improved earnings and long-term mobility for all workers, or did inequality subtly take hold over time?

These questions have become more urgent than ever, as recent years have seen economic inequality spark widespread backlash in countries like the United States. For Australia, the stakes are also high. With the release of the 2025 federal budget and a federal election just weeks away, national debates have intensified around key economic and social challenges, including the cost-of-living crisis, tax reforms, stagnating productivity growth, intergenerational inequality, structural budget deficits, and the impact of global uncertainty.

In a new study, we shed light on the fundamental factors underlying key election issues. Using the ALife dataset—a 10% random sample of all Australian taxpayers from 1991 to 2020—we explore how earnings evolved across different socioeconomic and demographic groups over the past three decades. Our focus is on earnings inequality, mobility, and volatility for workers aged 25 to 55, as we examine who experienced upward mobility, how fast, who fell behind, and who faced the greatest risk.

By applying internationally harmonised methods developed by the Global Repository of Income Dynamics (GRID), our findings offer valuable insights into Australia’s experience and allow for direct comparisons with other OECD countries, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. For more details and additional findings, please visit the Growth and Inequality in Australia Project website.

Key findings

1. Earnings grew in Australia, but not equally

From 1991 to 2020, median real earnings increased by about 30% for men and 40% for women, yet this growth was far from evenly distributed.

In the first two decades, high earners—particularly the top 10%—experienced growth nearly twice as fast as the rest. The very top (top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.01%) saw their earnings skyrocket during the 2000s mining boom, with their 1991 earnings doubling. This increasing concentration of income at the upper end of the distribution contributed to a rise in the Gini coefficient, from 0.34 to nearly 0.40 by the early 2010s (see Figure 2).

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the economic landscape began to change. Growth among top earners slowed, while women—across the distribution—continued to see steady progress. By the late 2010s, overall inequality had started to decrease, and the gender gap in inequality had not only narrowed but began to reverse.

Despite these improvements, inequality remained high compared to the early 1990s. Of particular concern is the stagnation among men in the bottom quartile, whose real earnings grew by only 15% over 30 years. Many of these workers faced significant earnings declines during economic slowdowns, including the 1990s recession and the post-GFC period, and their recovery was slow and incomplete. Their experience sharply contrasts with that of low-income women, who saw consistent earnings growth.

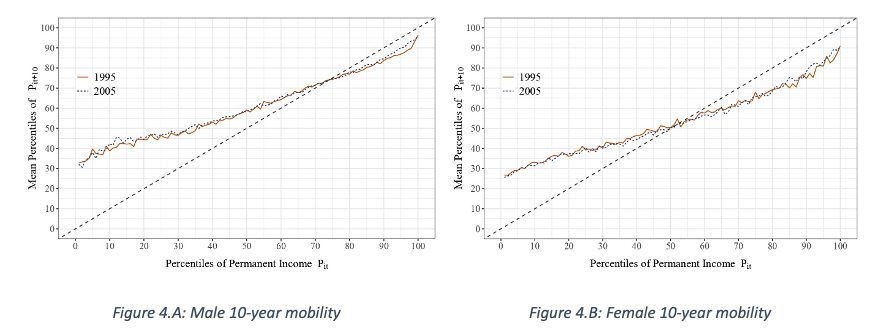

2. Early-life inequality has become more persistent

A particularly concerning trend is the increasing persistence of early-life disparities (see Figure 3).

Figures 3.A and 3.B depict the evolution of earnings inequality over life course, represented by the earnings gap between the top and bottom 10% of earners, across four cohorts who reached age 25 in 1991, 2001, 2006 and 2011. By following these cohorts over time, we distinguish the impact of initial labour market conditions from the inequality that develops due to events occurring later in their adult lives.

We observe that older cohorts, specifically those who entered the workforce before the GFC, experienced substantial changes in inequality over the course of their careers. Men, in particular, saw significant increases in inequality as they aged. This implies that adult-life factors—such as job changes, promotions, experience, and seniority—played a major role in shaping their inequality outcomes.

In contrast, younger cohorts display a different pattern: their earnings inequality was deeply ingrained from the outset. They saw relatively small within-group inequality change over time, suggesting that early-life factors—such as parental background, cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and education—had a stronger impact.

In today’s slower-growth economy, this trend indicates that economic opportunities are increasingly shaped by conditions at the starting line, with less room for upward mobility. These findings underscore the importance of further research into policies that promote more equitable early-life foundations, including in areas like early education, family support and workforce readiness, to help mitigate the long-term effects of entrenched inequality.

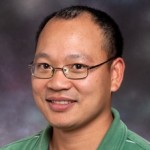

3. Upward mobility remains strong

Despite concerns about inequality, Australia has exhibited relatively high earnings mobility compared to other OECD countries. This is evident in Figures 4.A and 4.B, which show the average permanent earnings ranks of a worker a decade later, conditional on her initial rank (from 1 to 100). The initial rank is based on average annual earnings from 1997 to 2007. The 45-degree line thus represents zero mobility, where a worker’s income rank remains unchanged over a ten year period.

Two key observations emerge. First, both figures show a remarkable stability in earnings mobility across two time periods—1995 to 2005 (indexed as 1995) and 2005 to 2015 (indexed as 2005)—for men and women. Second, they indicate relatively high upward mobility. For example, a male worker initially at the 25th percentile (near the poverty line) during that period has a strong likelihood of reaching the median within a decade. Women’s upward mobility is somewhat lower than men, but still compares favourably to countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

As Australia navigate post-pandemic structural changes, preserving this mobility advantage will require more policy attention. However, due to data limitations, we cannot yet compute the long-term mobility of younger cohorts entering the labour market during the post-2010s slowdown. As a result, whether this strong mobility will continue remains an open question.

4. Earnings volatility affects some groups more severely

While average earnings have grown steadily, this has not translated into stability for all workers. Many face sharp and unpredictable fluctuations in their earnings. Low-income earners and young women, in particular, experience the highest and most persistent earnings instability. Men tend to encounter extreme negative shocks more frequently, whereas women often face more severe ones. Additionally, during economic downturns, both the frequency and intensity of extreme shocks rise. Notably, volatility increases for low earners while decreasing for high earners, further exacerbating the disproportionate impact of economic shocks on vulnerable groups.

5. The role of fiscal interventions

Australia’s institutional framework, with its progressive tax system and tightly means-tested welfare benefits, is designed to reduce inequality and promote mobility. Our analysis confirms that these policies have indeed helped reduce earnings inequality and cushion earnings volatility for low-income workers. By compressing top-end growth and boosting disposable incomes at the bottom, these redistributive effects are both real and significant.

However, the tax and transfer systems alone are not enough to counteract deeper structural changes. Inequality in pre-tax earnings remains largely driven by market dynamics. While fiscal interventions have play an important role in mitigating these forces, they have not been able to reverse them.

Policy lessons

Our findings highlight several key directions for future policy:

- Growth alone won’t solve inequality: Even during decades of sustained overall economic growth, income disparities widened as top earners advanced while low-income men were left behind. Inclusive growth requires intentional redistribution and targeted support for vulnerable groups.

- Invest early to reduce long-term gaps: As inequality becomes more deeply rooted in early-life conditions, policies focused on child development, education, and family wellbeing can yield significant long-term social and economic benefits.

- Preserve and strengthen upward mobility: Australia’s success on mobility should not be taken for granted. Understanding the factors that have supported this resilience is crucial for sustaining upward mobility, especially in today’s uncertain global economic climate.

- Use fiscal policies strategically but recognise their limits: While fiscal policies have helped reduce earnings inequality and volatility, long-term earnings dynamics are still largely driven by market forces. Questions such as why women continue to face heightened earnings instability, or why low-income men have been left behind, require deeper investigation into the structural drivers.

- Understand intra-household dynamics: Evidence from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey shows that secondary earners (often women) tend to increase their labour supply in response to large spousal income shocks, even when government supports are available. This raises a key question: has the growth in women’s earnings at the lower end of the distribution improved household welfare, or simply compensated for declines in male earnings? More research is needed to explore the role of earnings dynamics within families.

Conclusion

Australia’s long economic boom delivered many gains, but the benefits were not equally shared and came with considerable costs. As the country digests the 2025 Budget and prepares for an election amid growing global uncertainty, our findings offer a long-run perspective to help inform policy decisions on inequality, economic opportunity, and resilience. One message is clear: policy responses must move beyond focusing on averages. They must consider not only how much the economy grows, but who benefits, when, and why.

Further reading

Darapheak Tin, Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya, 2025. The Evolution of Earnings Distributions in a Sustained Growth Economy: Evidence from Australia. ANU Working Paper.

Darapheak Tin and Chung Tran, 2023. Lifecycle Earnings Risk and Insurance: New Evidence from Australia. Economic Record 99.

Recent Comments