We live in strange economic times.

Over the last few years, Australian business profits have boomed just as economic growth has trended down to ‘ultra-low’ levels. Australian leaders have crowed about a record-breaking run of nearly three decades without recession, while the country stumbled into per-capita recession. We look set for the first budget surplus in a decade, but median household incomes have fallen in the last decade due to wage stagnation for many. And the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has been further cutting interest rates that have already reached record lows.

Many commentators now suggest the best antidote to the strangeness would be higher government spending, especially on much-needed infrastructure and through increasing the welfare payments of those Australians living in poverty and thus most likely to spend immediately into struggling local economies. Indeed, with the RBA almost out of monetary ammunition and also warning that cautious consumers are prone to pay down record levels of private debt, stimulus-by-tax-cut looks tenuous. Forgoing a short-term budget surplus to boost both growth and government tax revenue down the track looks like a no-brainer.

Except to those in government.

In this blog I reflect on why. I suggest that the refusal of the Morrison government to even consider basic Keynesian demand management is about more than the electoral politics of delivering budget surplus.

A return to government spending designed to stimulate the economy would threaten the great fiscal shift of recent decades. This shift that has seen fiscal policy reoriented towards eroding progressive taxation and developing transfer mechanisms that divert tax revenue towards wealthier citizens and away from direct government spending on other things a state could address. The problem is that the few who benefit most from the new normal are unlikely to draw attention to it by bucking the trend – even to boost economic growth.

When the shift started?

One could assume the great fiscal shift started with the Hawke and Keating reforms of the 1980s and early 1990s, which saw the company tax rate fall from 49 per cent to 36 per cent, and the top rate of income tax fall from 60 per cent to 47 per cent.

Since the 1980s, neoliberal fiscal policy across the world has centred on such tax cuts, in line with supply-side theory developed by Arthur Laffer during the Reagan administration. In this view, cutting tax from overly high levels is seen to spur economic growth when optimally targeted at those who supply capital for investment. Sold through the popular rhetoric of ‘trickle-down’ economics, it has been enacted in many jurisdictions by large cuts to taxes on capital and upper band income tax rates—despite a paucity of evidence.

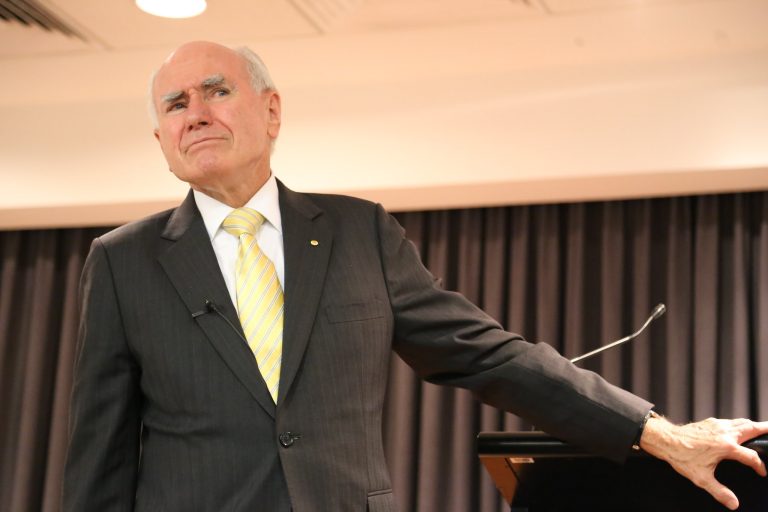

Yet the Hawke-Keating reforms also included the introduction of capital gains tax, the phased introduction of compulsory employer superannuation, the consolidation of universal public health provision through Medicare and increased welfare payments for lower income families. The great fiscal shift really gained momentum under John Howard (1996-2007).

Howard introduced a Goods and Services Tax (GST) and cut company tax to 30 per cent. He continued to cut income taxes for high earners but also boosted government payments and tax breaks for Australian residents—specifically those who undertake market transactions through consumption of services and financial investments.

In education, Howard reindexed the funding formula for Commonwealth contributions to private schools, removing the condition that per-student funding reduce in proportion to the overall economic resources of the school. The arrangements led to huge growth in federal funding. Private school students now receive three times the per capita federal funding of their public-school peers.

In health, Howard introduced a non-means tested 30 per cent government rebate on the cost of private health insurance. On the investment side, he raised the annual caps on tax-deductible superannuation contributions for those under 50 and made withdrawals tax-free for anyone above the defined retirement age (55-60 for most). He introduced cash refunds of dividend franking credits for share investors and, in 1999, a 50 per cent discount on capital gains tax payable on assets held for over a year.

Later, the focus changed to flattening the progressive income tax scale. In 2003, the threshold at which the top rate of income tax becomes payable was $62,500. By 2008, when Howard’s Labor successor Kevin Rudd fulfilled an election promise to implement Howard’s last tax package, it had become $180,000. (Other thresholds were barely adjusted.) According to the Australia Institute (Grudnoff, 2013) the annual ongoing cost to the budget of the 2004-08 income tax cuts stood at $39 billion by 2012.

Upward redistribution: at what cost?

Like the capital gains discount (around 50 per cent of capital gains are earned by the top 2 per cent of income earners), the income tax cuts were highly regressive. 42 per cent went to the top 10 per cent of income earners, who got more than the bottom 80 per cent.

Howard and successors also studiously avoided indexing the new tax thresholds, thus setting the basis for future bracket creep over time to increase average tax rates for lower deciles much more markedly than for the top decile. Using 2015 Treasury data, Daley and Wood (2016) projected the average increase for the top decile would be 0.4 per cent between 2015 and 2019, with all deciles from the 3rd to the 9th increasing by at least 1.4 per cent, and those around the middle being hit by 2-2.5 per cent.

The manipulation of indexation and thresholds meant the upwards redistribution was by stealth. Meanwhile, significant erosion of the value of parenting, disability and unemployment payments was also achieved under the radar through tweaking payment formulas while discontinuing a tradition of ad hoc increases. Austerity for those most in need through curtailed direct spending on welfare was the flipside of the largesse for the affluent.

The great fiscal shift lies in what all the changes added up to—and given that subsequent governments altered them very little—still add up to today. The Howard-Rudd income tax cuts still cost the budget around $40 billion a year. Removing tax on super in retirement phase cost around $2.5 billion in 2009-10, but this is increasing rapidly with the maturing of the super system. KPMG estimates the overall cost of tax concessions on superannuation will reach $50 billion a year by 2021. Federal subsidies for private health and education cost around $20 billion a year, cash refunds of franking credits, $5 billion, and capital gains discount, $10 billion.

When these costs to revenue are combined, it appears the great fiscal shift costs public revenue over $100 billion a year, most of which has flowed to wealthier Australians. The expense was initially covered by mining boom money, but once revenue declined it inevitably led to budget deficits. Yet the surplus politics we inherit today makes no reference to the radical reorientation of government revenue raising and spending patterns, or its costs.

The shift seems to be deepening

Indeed, as we try to make sense of strange times, it seems not only that surplus is sacred compared to state spending—even for vital economic stimulus—but that the priority of the government lies in deepening the great fiscal shift instead.

The recently legislated income tax package gives modest tax cuts to low and middle earners. But their value will soon be eroded by the magic of bracket creep. In 2024, they will be followed by a phase worth twice as much: reducing the 32.5 per cent income tax rate to 30 per cent, abolishing the 37 per cent bracket and raising the threshold at which the highest rate starts to $200,000. This will cost revenue around $20 billion a year, with a third of the benefit flowing to the top 10 per cent, and over half to the top 20 per cent. The Parliamentary Budget Office projects that the tax cuts will lead to large rises in average income tax rates paid by those on lower incomes, and tax rate cuts only for the top quintile.

When weak demand is a proximate cause of economic malaise, it would seem a bit odd for new income tax cuts to enhance further top-10-per-cent incomes that have recently risen faster than anywhere else in the OECD, while millions of highly indebted consumers are left with declining real incomes. But a cynic might point out that—just like the Rudd-Howard packages—MPs will receive the maximum benefit, which this time will be $11,640 per year for anyone earning $200,000 or more. (MP salaries start at $211,250.)

We might expect then that reversing the great fiscal shift is hardly likely to be top of our representatives’ to-do list.

What will the future hold?

With the huge cost growing, the efficacy of the shift must be questioned.

Australia now has the highest tax expenditures (tax revenue forgone due to special exemptions) in the world. Most don’t seem justified by policy outcomes. The majority of super tax concessions go to those who don’t need them, and Australian property prices started their ascent towards being the highest of any sovereign country straight after the introduction of the capital gains discount that benefits property investors. Residential property ownership has fallen fast.

Meanwhile, the OECD education chief identifies Australia’s increasingly unequal school system as a failing one, and health rebates subsidise insurance policies many don’t use because they are full of catches. And successive tax cuts with significant real-terms benefits only for the wealthy have coincided not with ‘trickle down’, but with rising inequality and a steady decline in the rate of economic growth.

If the cost of maintaining such priorities is ever-increasing austerity for a majority who do not benefit from them, perhaps the questioning will become somewhat louder—even if it is not led by the political classes.

Further reading

Redden, G 2019, ‘John Howard’s investor state: Neoliberalism and the rise of inequality in Australia’, Critical Sociology, vol. 45, nos. 4-5, pp. 713-728.

Recent Comments