While the phrase “lower taxes” was repeated half a dozen times in Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s 2019 Budget Speech, the gold medal for most repeated phrase was “without increasing taxes” (admittedly a tie with “strong economy”, each repeated 8 times).

In this blog piece, we ask whether this statement does in fact apply to all taxpayers in the Australian tax system.

Broadly, it is possible to increase taxes by either increasing the tax rate or increasing the tax base. Even though the Federal Government may not have increased tax rates, that is not the same as not increasing the tax take.

Taxes on multinationals

Indeed, in the period since September 2015 when now-Prime Minister Scott Morrison was appointed Treasurer, an onslaught of anti-avoidance provisions have been introduced and tightened. Most notably, the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (‘MAAL’), the Diverted Profits Tax (‘DPT’), the Anti-Hybrid rules, and tightening Thin Capitalisation rules.

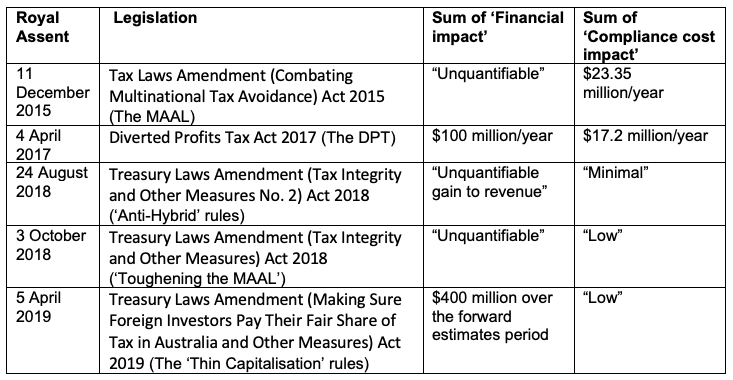

As indicated in the explanatory materials to each of these legislative provisions, each had an estimated positive financial impact on the tax take; ranging from $100 million per year to an “unquantifiable gain to revenue”. This is extracted in the summary table below:

Table 1. Estimated positive financial impact on the tax take

Indeed, in his 2019 Budget Speech, Treasurer Frydenberg himself acknowledged that the Government had implemented new laws “to crack down on multinational tax avoidance … which helped raise more than $12 billion”.

Taxes on superannuation

Looking beyond multinationals to taxes targeting high-salary earners making superannuation contributions, one of the most notable reform packages was the Superannuation Reform Package announced by then-Treasurer Scott Morrison in the 2016-17 Budget.

As stated in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016, this suite of amendments was estimated to increase the tax take by around $2.8 billion (yes, billion – not million) over the forward estimates.

This suite of superannuation reforms included, among other things, introducing the transfer balance cap, and lowering the concessional and non-concessional contributions caps.

Using Division 293 as a quick example, the threshold at which income earners would have to start paying Division 293 tax on their concessionally taxed contributions to superannuation was changed to $250,000 (from $300,000).

For those of us who are not superannuation buffs: Division 293 tax essentially works out at taxing concessional (that is, pre-tax deductible contributions) at an extra 15% on top of the 15% tax that is payable on them by the superannuation fund – so, effectively taxing them at 30%.

So, rather than increasing tax on higher-income earners, the impact of this reform was to tax high-income earners just as much as higher-income earners. This looks like a tax increase to us.

Let us stop using ‘tax’ as a dirty word

I hear you ask: “So what? Isn’t it good that the government is taxing multinationals and high income earners more?”

Perhaps, but then: why purport to be strengthening the economy “without increasing taxes”, and repeat that statement eight times in your Budget Speech? Especially since this is probably the most important speech in your political career to date and not an unscripted doorstop.

The Federal Government has itself announced (through explanatory notes to legislative amendments and in public speeches) that it has increased the tax take by nearly $15 billion extra as a result of just the above measures which it enacted.

We would simply, respectfully submit that this shows that ‘tax’ (just like the word ‘deficit’ – but we will leave that debate to the economists) is not always a dirty word, so let’s stop treating it like it is.

Other articles in the Budget Forum 2019

The Instant Asset Write-off Will Lift Investment—but Is That What We Want?, by Steven Hamilton

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 1, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 2, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Tax Offsets and Equity in the Scheme for Taxing Resident Individuals, by Sonali Walpola and Yuan Ping

Forecasts and Deviations – the Challenge of Accountable Budget Forecasting, by Teck Chi Wong

Targeted Tax Relief Makes the Tax System Fairer but the Economy Poorer, by Steven Hamilton

A Simpler Tax System Should Spark Joy—Eliminating Tax Brackets Sadly Doesn’t, by Steven Hamilton

A Budget That Supports Indigenous Australians?, by Nicholas Biddle

Women in Economics 2019 Federal Budget Reflections, by Danielle Wood

Tax Progressivity in Australia: Things Aren’t as Simple as They Seem, by Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya

Coalition and Labor Voters Share Policy Priorities When They Are Informed About Inequality, by Chris Hoy

Future Budgets Are Going to Have to Spend More on Welfare, Which Is Fine. It’s Spending on Us, by Peter Whiteford

Recent Comments