The Government has fired the starting gun on the election campaign, so it’s worth taking a closer look at some of the budget promises that form the basis of its election pitch to voters.

One of those promises is substantial and immediate tax relief—up to an additional $550 a year for some—delivered through a boost to the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset it introduced in last year’s budget. While this plan will certainly bring welcome relief to some taxpayers, the Government’s desire to target the reform at low- and middle-income earners has some potentially large hidden costs worth considering.

This post is the second in a three-part series, which began with my analysis of the Government’s plan to flatten the tax schedule. The key takeaway of this second part is that the more tightly targeted you want your tax system, the greater the economic damage it will do. There is simply no escaping this trade-off. Now the damage might be worth it but it’s critical to weigh the costs and benefits to be sure.

So what is the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset?

In last year’s budget, the Government introduced a new piece of tax policy called the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset (LMITO).

The LMITO cut your tax bill by up to $530 a year, but not everyone got that amount. Those on low incomes who don’t pay any tax got nothing—the offset isn’t refundable so it can only be claimed against the tax you owe. This replicated for slightly higher earners the existing Low-Income Tax Offset (LITO) that has applied to low-income earners for 30-odd years. The design of the LITO and LMITO is similar to a well-known American tax policy called the Earned-Income Tax Credit (EITC).

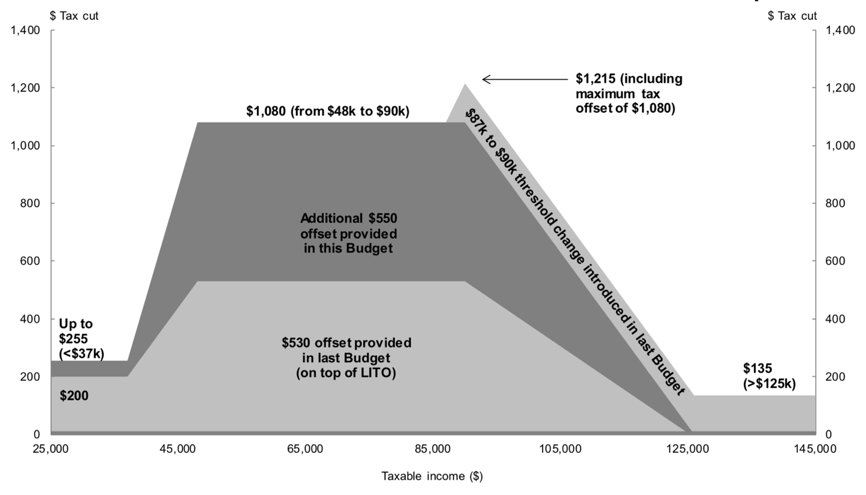

As shown in Figure 1, for those paying tax but earning less than $37,000 a year, the original tax cut was worth up to $200. Between $37,000 and $48,000 of yearly earnings, the tax cut then ramped up to the maximum of $530 where it stayed until you earnt $90,000 a year, when it phased down gradually to nothing when you earnt $125,000 a year. In this year’s budget, the Government has kept the thresholds the same, but raised the minimum cut to $255 a year and the maximum cut to $1,080 per year.

Figure 1: Tax cuts implied by Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset

(Source: Commonwealth of Australia)

This framing as a tax offset—that is, as a reduction in the tax you owe—has really only one thing going for it: it’s a very clear way to communicate a tax cut to voters. The policy tells you exactly what tax cut you’ll get based on your income, which can be represented clearly in a nice chart (see again Figure 1). It’s the perfect ammunition for an election campaign.

A tax offset is just a change to the tax schedule in disguise

While this framing as a tax offset might be great for winning elections, it makes the task of understanding the tax you owe at any given income level unnecessarily difficult.

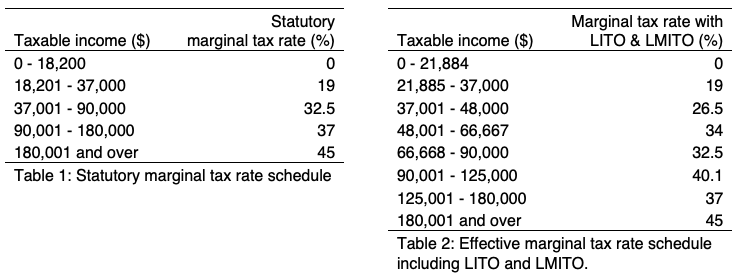

Australia’s statutory tax schedule (see Table 1 below) is fairly straightforward—a set of clearly laid out tax brackets with progressively increasing marginal tax rates. But that simple tax schedule is a ruse—it tells you next to nothing about the true marginal tax rate you face.

That’s because Australia’s income tax system layers on top of this basic schedule a raft of adjustments variously called “offsets” and “surcharges”, amongst others. Some of these adjustments do nothing more than modify the tax schedule at different incomes. Others modify it based on other characteristics, such as whether you are part of a family or your age. The LITO and LMITO fall into the former category.

Now there might be good reasons to adjust the tax schedule on bases other than income. But introducing a separate tax offset, rather than simply adjusting the tax schedule directly, does nothing but reduce the transparency of the tax system. It might make voters better understand the tax cut they’re offered in an election campaign, but it makes it a lot harder for those very same voters to understand their true circumstances come tax time.

I’m a tax professor who teaches tax-system design to hundreds of students a year, and I can tell you that I had a hard time figuring out exactly how these overlapping policies net out to what would otherwise be a very straightforward set of tax rates. This is something Ken Henry, in his 2010 review of the tax system, railed against and something highlighted around the same time by officials in the Treasury department. Indeed, the former Labor government embarked on a plan to eliminate the LITO but that course was reversed and the concept radically expanded under the current government.

So what does the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset do to the tax schedule?

A standard tax schedule works on the basis of what we call marginal tax rates. That is, a particular tax rate applies only for those dollars earned within a corresponding range.

Take a look at Table 1, below. In the standard case, everyone pays the same 19% tax rate on their 18,201st through 37,000th dollars of income, regardless of how high their final dollar of income is. If the Government were to cut the tax rate in that bracket by 1 percentage point, then everyone earning more than $37,000 would get a tax cut of $188 because $18,800 of their income is now taxed at a 1-percentage-point-lower rate. But the tax they’d pay on their final dollar of earnings—and thus their incentive to earn an additional dollar—would be unchanged.

Because the same tax cut would be received by so many people on higher incomes, it might be less fair and more expensive than we want. If instead we want to target the tax cut only at modest earners, then we must take it away from high earners. And there’s a simple way to do that. If additionally we raise the marginal tax rate applying to a higher bracket, then everyone whose final dollar of earnings falls above both brackets can be left with no net tax cut at all—the cut in the first bracket gives them some money and the hike in the subsequent bracket takes it away.

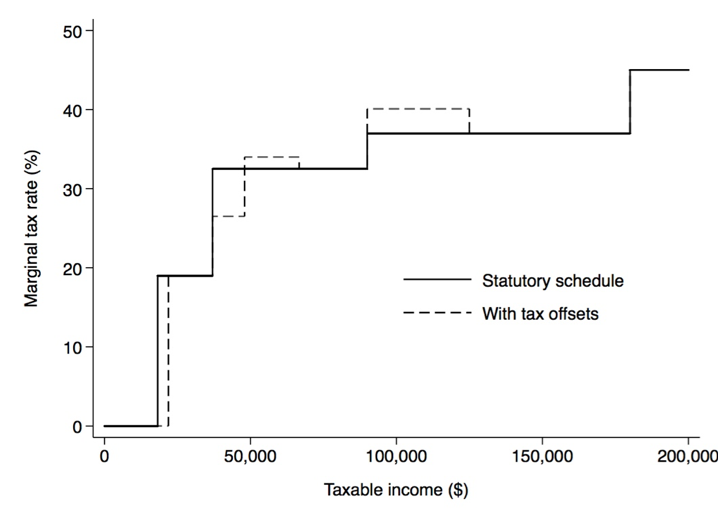

This is, in principle, exactly how the LMITO works. You can see in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2 that the LITO and LMITO lower the tax rate for all earnings between $37,001 and $48,000 from 32.5% to 26.5% but raise the tax rate for all earnings between $90,001 and $125,000 from 37% to 40.1%. That’s right: the LMITO raises the marginal tax rate for a whole swathe of taxpayers. But do you think you’ll find any mention of an increase in tax rates in the budget papers? (Hint: no!)

Figure 2: Marginal tax rate schedule with and without the LITO and LMITO

Figure 2: Marginal tax rate schedule with and without the LITO and LMITO

The hidden cost of tax offsets

Recasting the LMITO in this way clarifies the trade-off at its heart: we can absolutely target tax relief at low-income earners but this must come necessarily at the cost of higher marginal tax rates for higher-income earners.

It’s a classic example of what we call the equity-efficiency trade-off. Arthur Okun, an adviser to US President Lyndon Johnson, described it thusly: redistributing income is like transporting water from one place to another in a leaky bucket—you can do it, but you’d better be prepared to lose some along the way. In much the same way, you can cut the tax paid only by low earners, but that means high earners must face higher marginal tax rates, reducing economic activity at least to some degree. The critical question is: just how leaky is the bucket?

Marginal incentives are worsened only for the roughly 700,000 Australian taxpayers earning between $90,000 and $125,000 a year. For every additional dollar they earn, the Government now takes away an extra 3 cents. That might not sound like much, but the evidence suggests it will have an effect.

In what kinds of ways? Well, the marginal tax rate increase lowers the benefit of additional taxable income. The most obvious response would be to work fewer hours, for example through less overtime or working fewer days per week. Secondary earners are particularly prone to this response. But it also could mean not going for promotions or pay rises where those are costly, for example by not skilling up or not putting in additional effort. As I show in recent work, it also could involve claiming more deductions than you otherwise would.

So what will the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset cost the economy?

There are a multitude of possible responses, all summarised in a reduction in taxable income. And in case you don’t believe that people do, in fact, reduce their taxable income in response to increases in marginal tax rates, there is extensive evidence that should convince you otherwise.

In my aforementioned work, relying on data for the Australian tax system, I showed that a 3 percentage-point increase in the marginal tax rate results in an average reduction in taxable income of around 0.6 percent. For someone earning $125,000 a year, that amounts to a reduction in taxable income of $750 a year. If we assume the average affected person earns in the middle of the relevant range, then this implies an aggregate reduction in taxable income of almost half a billion dollars a year. That means around $300 million less in consumption and saving, and around $200 million less in income tax revenue.

This is the real, measurable cost of targeting tax cuts. When economists talk about the “distortion” or “deadweight loss” generated by higher tax rates, this is what we mean. It is the cost of fairness. Whether the cost is worth it is entirely a subjective question. Evidently, the Government has decided that it is. And we must all make our own determination at the ballot box, ideally armed with full information.

But it is a concern that the framing of the policy, while politically advantageous, obscures the implicit increase in marginal tax rates and therefore its very real economic cost. Bundling all of these overlapping surcharges and offsets into one true tax schedule, as recommended by the Henry Tax Review, would do meaningful good to the transparency and understandability of the tax system, so we may be better informed about how the tax system affects us all. And so our decisions at the ballot box may be fully informed.

Other articles in the Budget Forum 2019

The Instant Asset Write-off Will Lift Investment—but Is That What We Want?, by Steven Hamilton

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 1, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 2, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

“All Without Increasing Taxes”? A Closer Look at Treasurer Frydenberg’s Refrain Repeated Eight Times in His Budget Speech, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Tax Offsets and Equity in the Scheme for Taxing Resident Individuals, by Sonali Walpola and Yuan Ping

Forecasts and Deviations – the Challenge of Accountable Budget Forecasting, by Teck Chi Wong

A Simpler Tax System Should Spark Joy—Eliminating Tax Brackets Sadly Doesn’t, by Steven Hamilton

A Budget That Supports Indigenous Australians?, by Nicholas Biddle

Women in Economics 2019 Federal Budget Reflections, by Danielle Wood

Tax Progressivity in Australia: Things Aren’t as Simple as They Seem, by Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya

Coalition and Labor Voters Share Policy Priorities When They Are Informed About Inequality, by Chris Hoy

Future Budgets Are Going to Have to Spend More on Welfare, Which Is Fine. It’s Spending on Us, by Peter Whiteford

If you can go little but in more in depth analysis of the tax impact on the economy.

“That means around $300 million less in consumption and saving”

Why do you bundle consumption and saving when they have opposite macroeconomic effects on demand?