The release of the Australian budget next week is so much more than a series of financial statements. It is a statement of what the Government values.

Whether it be tax cuts over increases in the Newstart allowance, or increases in spending in infrastructure as opposed to health and education, policy choices come down to priorities. How these trade-offs are balanced in an election year is (we would hope) based on what the Government believes everyday Australians want prioritised. Numerous polls of the Australian population show that these priorities are deeply divided down party lines, with Coalition voters preferring tax cuts and Labor voters preferring increases in public spending.

However, the policy priorities of Australians appear to be based on large misperceptions about the extent of inequality. For example, a 2014 study by Harvard Professor Michael Norton shows that Australians perceive the richest 20% of our society as only four times wealthier than the poorest 20%. In reality, the richest 20% in Australia are over 60 times wealthier than the poorest 20%. Another example of misperceptions of inequality in Australia can be seen in a 2019 cross-country study by Hoy and Mager, which shows that most Australians think that they are middle class regardless of whether they are rich or poor.

These studies illustrate that along with people’s voting preferences, people’s perceptions of inequality are the key determinants of what policies they want prioritised. This raises the obvious question, would Australians’ preferences for policies change if they had accurate information about inequality? And if so, would this reduce differences in policy priorities between Coalition and Labor voters?

Randomised survey experiment: respondents received either information about inequality or personal income position or no information

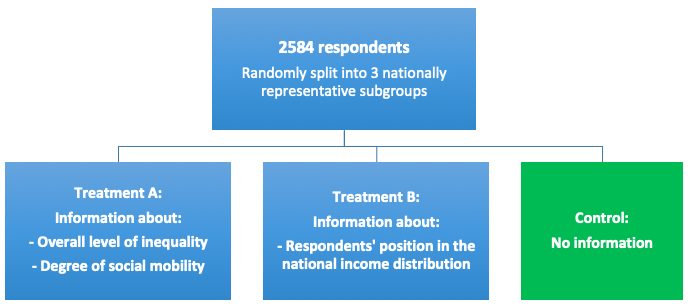

Our paper (joint work with my co-author Russell Toth) answers these questions. A randomised survey experiment of a nationally representative sample of 2,584 Australians was conducted using the polling company IPSOS.

Respondents were randomly allocated to either receive information about the level of inequality and mobility in Australia (Treatment A), their position in the national income distribution (Treatment B), or no information (Control) – see Figure 1 below. After receiving this information people were then asked about whether they want the government to do more to address inequality and what policies they want prioritised.

In addition, we provide respondents with an extra dollar for completing the survey that they could either donate to the Smith Family (a charity that aims to help Australian children break free from poverty), the Cancer Council of Australia or keep for themselves.

Figure 1: Design of randomised survey experiment

Coalition voters became more progressive after being informed

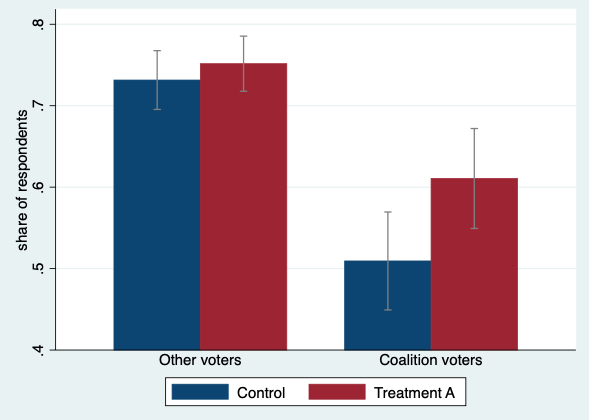

We show that providing respondents with information about inequality and mobility in Australia makes them more likely to desire urgent action from the government to reduce inequality, more supportive of providing free and high-quality health and education, and less supportive of cutting corporate taxes. This effect was largely due to Coalition voters becoming more progressive in their views (see example in Figure 2). In other words, correcting this misperception reduced the gap in policy differences between Coalition and other voters.

Similarly, correcting beliefs about respondents’ own position in the national income distribution led those who were told they are poorer than they expected to become more supportive of urgent action by the government to address inequality. Once again we show this effect was almost entirely driven by Coalition voters.

Figure 2: Differences between desire for urgent action for the government to reduce inequality between respondents in treatment group A and the control group, by type of voter

We also show that information about inequality leads to convergence between the level of charitable giving provided by Coalition and Labor voters. However, unlike the level of support for government-led redistribution, Coalition voters in the control group are more likely to donate than other types of voters (even after controlling for background characteristics like income). Both treatments lead Coalition voters to be less likely to donate to the Smith Family. The information effect was large enough to close the pre-existing difference in charitable giving between Coalition and Labor voters.

Collectively, our findings illustrate that existing misperceptions of inequality in Australia cause greater polarisation across the political spectrum than would be the case if people had accurate information. A lack of accurate information about the current distribution of income partly contributes to Coalition voters preferring low levels of government-led redistribution. In addition, we show that differences in preferences for redistribution between Coalition and Labor voters cannot be simply dismissed as differences in levels of compassion or empathy as Coalition voters were more generous in terms of charitable giving than other types of voters.

There is cross-party consensus on one issue: Newstart is too low

The vast majority of Coalition and Labor voters believe the current level of Newstart payment is too low. Our survey asked respondents what the appropriate level of Newstart should be. Around two-thirds of Coalition voters and over 75% of Labor voters stated amounts over $40 a day (it is currently $39 a day). Almost half of respondents stated amounts over $60 a day.

Our study reveals that once Australians are better informed about inequality they become far more supportive of the Government prioritising redistributing income from rich to poor. We will have to wait until next week to find out whether the Government will rely on the misperceptions of everyday Australians to implement policies in the budget that would be far less popular if people had accurate information.

Other articles in the Budget Forum 2019

The Instant Asset Write-off Will Lift Investment—but Is That What We Want?, by Steven Hamilton

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 1, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 2, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

“All Without Increasing Taxes”? A Closer Look at Treasurer Frydenberg’s Refrain Repeated Eight Times in His Budget Speech, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Tax Offsets and Equity in the Scheme for Taxing Resident Individuals, by Sonali Walpola and Yuan Ping

Forecasts and Deviations – the Challenge of Accountable Budget Forecasting, by Teck Chi Wong

Targeted Tax Relief Makes the Tax System Fairer but the Economy Poorer, by Steven Hamilton

A Simpler Tax System Should Spark Joy—Eliminating Tax Brackets Sadly Doesn’t, by Steven Hamilton

A Budget That Supports Indigenous Australians?, by Nicholas Biddle

Women in Economics 2019 Federal Budget Reflections, by Danielle Wood

Tax Progressivity in Australia: Things Aren’t as Simple as They Seem, by Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya

Future Budgets Are Going to Have to Spend More on Welfare, Which Is Fine. It’s Spending on Us, by Peter Whiteford

Recent Comments