In 2015, Australia’s Commonwealth income tax reached its first century. The Income Tax Assessment Act No. 34 of 1915 and accompanying Income Tax Act No. 41 of 1915 were assented to on 13 September 1915 “by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, the Senate, and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Australia”.

A history of income taxation in Australia can be found in Smith (2004).

In this centenary year, the income tax is under scrutiny again following the release in March 2015 by the Australian government of the Re:Think Discussion Paper aimed at a “national conversation” on tax reform.

A new tax to fund war and for social reform

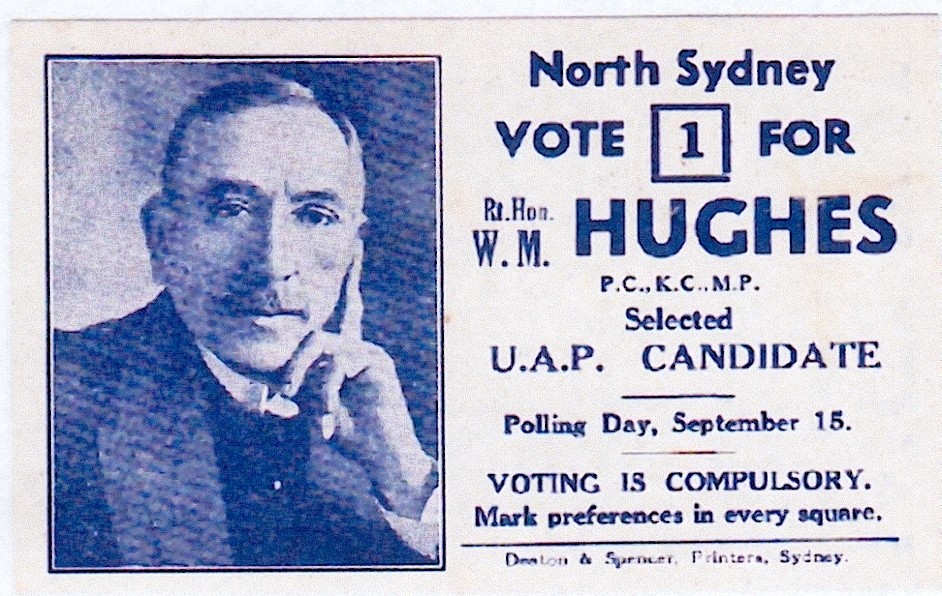

In 1915, both sides of politics accepted the need for the federal income tax to raise revenues during World War I. The income tax was introduced by Mr Billy Hughes in the Labor Government, then Attorney General under Prime Minister Fisher. The Government had just been re-elected after a double dissolution and with a majority in both Houses – useful, if not essential, in achieving major tax reform. Not long after, Billy Hughes as Prime Minister attempted to introduce conscription for World War I, and was famously expelled from the Labor Party as a result.

On introducing the new federal income tax, Mr Hughes said:

“That additional revenue is necessary to meet the great and growing liabilities created by the war is amply apparent, and the Government has decided that this can be best raised by an income tax. … I have always regarded this form of direct taxation as peculiarly appropriate to the circumstances of a moderate community; … not only an effective means for raising money for the conduct of government, but serving as an instrument of social reform.”

…or a policy of frightfulness?

The Leader of the Opposition, Mr Joseph Cook (Parramatta), recognised how an income tax is “peculiarly appropriate in time of war” but was cautious about the implications of this “entirely novel” tax at the Commonwealth level.

Mr W Elliot Johnson MP (Lang) presciently observed that “there is all too much reason to believe that this taxation will not end with the war”:

“To me it seems only part of a policy of frightfulness in taxation for which the war is made the excuse by honourable members opposite.”

Our most important tax

The Australian federal individual and company income tax provides the lion’s share of tax revenues in Australia today. In 1915, income taxes raised only 6 per cent of tax revenues. By 1939-40 this was 34 per cent, but three quarters was still raised by the States. In 2013-14, the personal income tax, with the Fringe Benefits Tax and superannuation fund taxes, raised $173.7 billion, while company income tax (including petroleum resource rent tax) raised $68.6 billion (Table 7, from Budget Paper Number 4). The total of $242 billion comprises 70 per cent of federal tax revenues, and is nearly five times the revenues raised by the Goods and Services Tax.

Income tax in the federation

In 1915, all States had their own income taxes – although some states, including Queensland, had only enacted these after federation. Joseph Cook said:

“In providing for a Federal income tax, we cannot overlook the machinery and taxation of the States. The essence of Federation, as I understand it, is not to cut across State legislation unnecessarily, nor to interfere with State obligations. To say this is not to lay oneself open to the accusation of undue solicitude for State rights. … It was thought that the States and the Commonwealth would work in harmony, each complementing and buttressing the other, instead of acting as jarring factors, which has too often been the case.”

He was concerned about the combined high level of taxation by both governments:

“Now, after the State Governments have each had their cut at the incomes of the people, the Commonwealth is proposing to make its cut, which is to be very severe.”

State and local rates and taxes, including State income tax and land tax, were deductible from the income tax – consequently, the Commonwealth income tax took up the residual after the State income taxes applied. State governments continued to levy income taxes until 1936, when income tax powers were handed over to the federal government, and finally in 1942, the Uniform Income Tax Plan replaced existing State income taxes.

The Income Tax of 1915

The 1915 income tax base was largely confined to ordinary income derived in Australia. Deductions were allowed for losses or outgoings actually incurred in Australia. Capital gains were not taxed. Like the United Kingdom, Australia did not tax capital gains (or allow a deduction for capital losses) until we enacted a specific statutory regime in 1986. This contrasts with the United States, which taxed capital gains as income from inception of its federal income tax, although later introducing preferential rates.

The 1915 Act was closer to a comprehensive income base than our current tax law in one way. It taxed imputed rent by including 5 per cent of the capital value of the home, offset with the interest paid on any mortgage. This was repealed in 1923.

Famously, the first Income Tax Act was only 22 pages long. Today, we have two income tax statutes, comprising many thousands of pages in both the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 and the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936.

Progressive Tax Rates

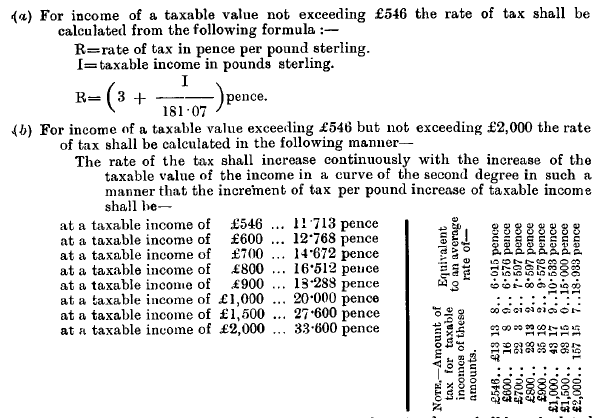

The 1915 income tax contained a significant innovation in a continually increasing progressive marginal tax rate structure. This rate structure baffled most people.

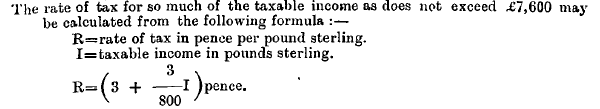

The personal income tax rate was 60 pence in the Pound (about 25 per cent, as there were 240 cents in a Pound), and below it, the rate of tax per pound sterling was 3 pence and 3 eight hundredths of one penny increasing uniformly with each increase of One pound sterling.

First Schedule of Income Tax Act 1915

Second Schedule of Income Tax Act 1915

Even Mr Hughes who introduced the Bill said:

“I can hold out no hopes of such simplicity with regard to the second schedule relating to the taxation of incomes derived from property. There is a difficulty in the formula which I am unable to express other than in the terms of higher mathematics. I am credibly informed it has something to do with the perturbations in the curve.”

Mr Maloney (Melbourne) said:

“One Assistant Minister made an heroic effort to show me how the rate could be ascertained in any case, but he landed himself and myself in a Serbonian bog of difficulty. I then tackled a mathematician who has shone very highly in the University examinations, but he told me that he could not tell me how the rate could be ascertained in any given case. It was impossible for him to do so, because the formula was built upon wrong premises.”

It seems only one person, the redoubtable Mr Knibbs, the Australian Statistician, actually understood it. The continuously increasing rate curve was soon dropped from the law, but a stepped progressive rate structure remains a core feature of the federal income tax.

The company tax

Prime Minister Hughes’s speech about the income tax showed he was concerned about enterprise and economic growth. His speech on these matters could as easily be given in 2015 as in 1915. Hughes said:

“it is necessary to consider not merely the requirements of the revenue, but also the incidence of the tax, so that the economic equilibrium may be disturbed as little as possible. Australia is a very rich country, her production per capita being very great; perhaps the greatest in the world. … A country’s productivity is the measure of its labour force, its energy and its resources. The productivity of labour depends mainly upon two things: the amount of capital available and the manner in which it is being used, and the efficiency of the labour. At this juncture it is of the utmost importance that we shall do nothing to discourage enterprise…”

In the 1915 Act tax was levied on companies at a rate of one shilling and six pence for every pound sterling, a rate of 7.5 per cent. A deduction was allowed for distributed profits which were taxed to shareholders at their personal rate. The “double tax” classical system of company-shareholder taxation was established later in Australia and then wound back through the dividend imputation system introduced in 1987.

Reflecting Australia’s insular economy in 1915, as well as feasibility of tax collection, the 1915 income tax was territorial, levied on taxable income from sources within Australia. In 1930, as the government sought increased revenue, this was amended to apply to worldwide income of Australian residents.

This led to the possibility of international double taxation, but Australia’s first tax treaty to alleviate double tax, with the United Kingdom, was not signed until 1946. Today, rely on our network of 45 bilateral tax treaties and on our foreign tax credit regime to prevent double taxation for individuals.

Today, in an era of increasing cross-border capital investment, Australia has reverted to a territorial system for companies. Overseas business profits of Australian resident companies are exempt from company tax, but tax applies when distributed to shareholders. Our dividend imputation system has the effect of a classical system for foreign shareholders, introducing a bias towards debt for cross-border investment.

As we go about our national conversation on tax reform in 2016, we should remember that resilience of the income tax – our core tax base – is critical for Australia.

This article is based on the Introduction to the special issue of Australian Tax Forum on the centenary of the income tax, Stewart M, 2015. Looking forward at 100 years: Where next for the income tax? Australian Tax Forum.30(4) 667-677.

Recent Comments