The Oceania region includes countries with some of the best – which is to say: most transparent, most rigorous, and most accountable – budget processes in the world. This is particularly notable in Australia and New Zealand. However, other countries in the region need to catch up in terms of best practices in the budget process. How can this be done?

In a recent paper published in the Australasian Parliamentary Review, we assessed the merits of establishing a Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) in Fiji by examining how such an institution would fulfill two important roles: first, by assisting in the oversight of the budget process; and second, by supporting coordination among key accountability institutions such as the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) and the Auditor General (AG) in their fiscal oversight roles, which is a role specific to Fiji’s accountability ecosystem and which stems from the uniqueness of the Fijian context itself.

Parliamentary Budget Offices (PBOs) are independent offices that produce non-partisan and impartial analysis on matters and policies pertaining to budgeting and finance, including the budget itself, for the consumption of legislators who then use the PBO’s analysis to inform their legislative budgetary duties including debate, legislation, and fiscal oversight.

The PBO model has received growing attention worldwide, with nearly 60 countries at presently possessing the equivalent of an ‘Independent Fiscal Institution’ (IFI) attached to their legislatures. But the scant literature on the subject points to a great deal of ambiguity on what precisely the PBO model should do. To this point, there are also challenges in the measurement of how effective PBOs are.

However, the ambiguity around PBOs allows for innovative roles to be assigned to them. We used Fiji’s unique circumstances to consider the application of PBOs not just as repositories of budget acumen, but also as a coordination mechanism for accountability institutions, a role that would be unique among the PBOs of the world.

Fiji as an emerging model in budget expertise?

The uniqueness of budget oversight institutions in Fiji is attributable to a multiplicity of factors, including: a bicultural demography; a colonial Westminster political heritage; a legislature made unicameral in 2013; a series of tussles between civilian and military regimes; and a large population compared with other Australasian island republics.

In Fiji, the oversight role suffers from an inherent fragmentation. Although it has had core oversight institutions in place since (and even before) independence, these institutions (the Auditor General and the Parliamentary Accounts Committee) have not devised a coordinated effort to oversee policy more broadly and budgets specifically. Furthermore, executive-opposition party dynamics have become slightly less conducive to budget oversight in the very recent past. In 2016, the Standing Orders of Parliament (117) relating to the Chairmanship of the Public Accounts Committee were amended, such that the PAC would be chaired henceforth by a member of the executive party instead of the opposition. The chair of the PAC resigned and said that the committee had become “toothless”. The government argued that amendment was made because the PAC was acting beyond its jurisdiction and was becoming very political.

These challenges notwithstanding, a new constitution was adopted in 2013 to breathe new life into the Fijian governance ecosystem. Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, the current (34th) Attorney-General, as well as Minister of Finance, unveiled a constitution that was notable for its vocal support of increased ‘transparency and accountability’ and ‘good governance’ in the Fijian system, as enshrined in the very first article of the document.

Two Roles: A Pacific innovation

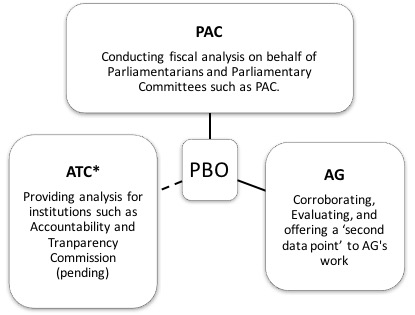

Our work has found that a PBO in Fiji can act as a “coordinator” of budget oversight activities by providing the Public Accounts Committee, the Auditor General, and the Accountability and Transparency Commission, with impartial and non-partisan budget analysis pertaining to fiscal oversight.

Figure 1 – A Simplified Relationship between the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) and the major accountability institutions: Public Accounts Committee (PAC), The Auditor General (AG) and other institutions such as the Accountability and Transparency Commission (ATC*: constitutionally mandated but yet to be established)

From the Public Accounts Committee perspective, as members of the PAC do not themselves necessarily possess the fiscal acumen to scrutinise a complex document such as the national budget, which approximates $2.5Bn Fijian ($1.2Bn USD) in total operating receipts, the PBO can serve as a legislative tool to enable long-term oriented, unbiased, detailed budget analysis.

From the Auditor General’s perspective, the PBO would serve as a second data point of comparison with the AG’s analysis, and muster a position of ex ante oversight that complements the ex post oversight role of the AG. Having two unbiased and separate analyses on a key issue adds analytical rigor to its study. As a matter of best practice, the PBO should not provide analysis only to the PAC, but share its findings in an ‘open publishing’ format that is accessible to all parliamentarians, to the media, and to the general public.

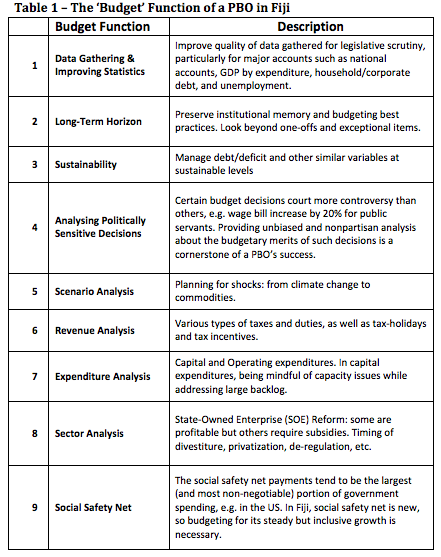

Aside from this role as a coordinator, there is a purely budget analysis role for the PBO to play as well. Fiji is in a state of economic transition wherein budget analysis is prone to a measure of uncertainty, which is attributable to exogenous factors such as alterations in commodity prices, currencies, export revenues, investor appetite for privatisation, cost of borrowing, among other variables; but also to endogenous factors such as a more stable political climate, successful completion of infrastructure projects, investment in the social safety net, programs to subsidise or deregulate SOEs, among other variables. The PBO can bring a long-term orientation to budget analysis and foster greater reliability in legislative decision-making through superior data collection. Furthermore, while the Reserve Bank of Fiji also conducts budget analysis, the PBO’s work would add another nonpartisan set of “data points” on budget work, a point which has been noted in other countries as an important part of a PBO’s value proposition.

Challenges

The dual roles that our research proposed will face many of the same challenges that PBOs face elsewhere. PBOs are often constrained by limited resources in terms of funding and staffing. They also face legal/mandate restrictions, and they may find themselves unable to access the necessary information to execute more robust analysis. Moreover, they do not have “enforcement powers”, meaning that their work is normative, suggestive, or advisory, but it cannot compel other institutions to heed its analysis. But in many cases, such issues do not halt a PBO’s work; they simply make it quite difficult, and PBOs often find creative ways to deal with their limited endowments.

Reference

Chohan, UW & Jacobs, K (2017). A Parliamentary Budget Office in Fiji: Scope and Possibility. Australasian Parliamentary Review. Vol 31 (2), 117-131.

Recent Comments