Editor’s note: This is an extract of a speech given by Danielle Wood at the Women in Economics post-Budget event, held at the National Press Club of Australia on 16 May 2017. Speeches by two other speakers can be accessed here and here.

Thanks Katherine and to the National Press Club for having us. I’m absolutely thrilled to be here to participate in what I believe is the first all-female economic discussion to be hosted by the Press Club. Part of the vision of the Women in Economics Network is to raise the prominence of female voices in the national economic debate. Events like this clearly contribute to the goal.

The good news: Budget repair

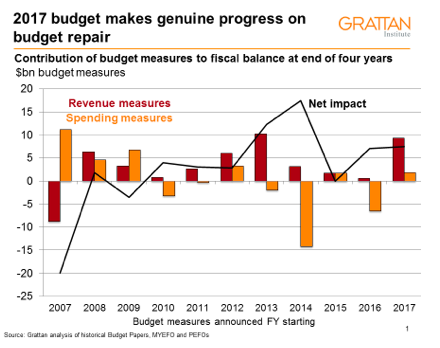

The government has made some serious headway on budget repair. Overall the measures in this budget represent a $7 billion improvement in the bottom line in 2021. The real figure is closer to $11 billion once you take into account the fact that the starting position was artificially inflated by the so-called “zombie measures” from the 2014 and 2015 budgets. The government has done the right thing in finally letting these go.

Figure 1

The Grattan Institute and many other commentators been asking the government not to ignore the revenue side of the budget in trying to achieve budget repair. There is no longer a danger of that. Almost all the budget repair effort comes from higher taxes: $5 of every $6 raised by budget measures are on the revenue side.

There may be issues about how these taxes are being raised; probably we could be doing it better. However, this certainly signals a serious shift in the way the government is thinking about its budget repair efforts.

The efforts by this government to fix the structural problems in the budget are to be commended. The run of deficits since 2009 has left net debt levels climbing. Net debt is estimated in the budget to peak at 19.8 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 but it will probably go higher. This has left the next generation with a growing interest bill. Every time the government runs a $40 billion deficit, the lifetime tax burden for every 25-34 year old increases by $10,000. This also leaves less room for the government to respond in the event of another serious economic downturn.

But even with the repair efforts in this budget, a balanced budget is still a distant fantasy. The budget suggests we will return to surplus in 2021.

Figure 2: Budget forecasts

This is about as credible as the projected surpluses from the last 7 budgets – none of which ended up happening.

This is about as credible as the projected surpluses from the last 7 budgets – none of which ended up happening.

Figure 3:

The budget numbers are based on optimistic assumption, both in terms of the future of the economy and the way in which this translates into tax collections. The wages growth assumptions are particularly heroic. You have to be firmly in the “glass half full” or even the “glass overflowing” camp to believe wages growth will pick up from a sluggish 2% this year to 3.75% in 2021, on par with growth during the mining boom. If wages instead continued to grow at 2 per cent, income tax collections would be $12.2 billion lower in 2021.

The budget numbers are based on optimistic assumption, both in terms of the future of the economy and the way in which this translates into tax collections. The wages growth assumptions are particularly heroic. You have to be firmly in the “glass half full” or even the “glass overflowing” camp to believe wages growth will pick up from a sluggish 2% this year to 3.75% in 2021, on par with growth during the mining boom. If wages instead continued to grow at 2 per cent, income tax collections would be $12.2 billion lower in 2021.

Figure 4:

The government is also banking on a more than 30% increase in company tax receipts and 60% increase in capital gains tax receipts by 2021. Similarly large increases forecast in past budgets have failed to materialise.

The government is also banking on a more than 30% increase in company tax receipts and 60% increase in capital gains tax receipts by 2021. Similarly large increases forecast in past budgets have failed to materialise.

The trouble with optimistic numbers is that if you believe the budget will float back to surplus without much effort – where is the imperative to make the hard decisions? It is hoped that Treasury will revisit its projection methodology, so that the scale of the budget repair problem is more obvious.

In going “all in” on taxes, there may be a temptation to relax on the spending side. Of course, not all extra spending is “bad debt”. The budget includes some valuable and well targeted new spending on schools and health. But there seems to be no effort to trim fat elsewhere – other than the university sector.

It is true that the Senate makes spending cuts hard and the Opposition seems to be egging the government on in a spending race. But the’re areas where savings would be reasonable. A good start could involve measures such as: including the family home in the age pension asset test; driving better deals on pharmaceutical pricing; shifting away from a direct action policy to a market mechanism for carbon abatement; and better targeting the almost $500 million in new regional spending announced in this year’s budget. It is also hard to believe that the large and quickly growing defence budget – the only area where we make specific targets for funding to grow as a share of the economy – couldn’t be delivered more efficiently.

Debt and infrastructure

We heard a lot about “good debt” and “bad debt” in the lead up to the budget. Instead what we have is good debt, bad debt and invisible debt. The government has announced substantial new investments including $8.4 billion on the inland rail, $5.3 billion on Badgerys Creek airport, which are all sitting off balance sheet. This is exactly what the previous government did with the NBN.

This invisible debt is only justified if the government expects to make a commercial return on the projects – that is, if the stream of payments it generates covers the cost of interest and of paying off the infrastructure over its working life.

If these projects are indeed commercial, it is unclear why the government needs to be involved. On the other hand, if the expected returns are too low to warrant private sector involvement, they should be on balance sheet. Even then, there is the question about whether these projects would be “good debt”. Infrastructure Australia finds that inland rail will deliver one-dollar-and-ten-cents economic benefit for every $1 of costs; but there are a lot of downside risks. Grattan’s Cost Overruns report showed that on average, Australian transport infrastructure projects end up costing 24% more than forecast. And bigger projects have bigger average cost overruns.

When the government pursues risky and uncommercial projects off balance sheet it is future generations bear the cost.

An intergenerational definition of fairness

In Budget 2017-18, we have heard a lot about fairness. This is a plea for a broader definition of fairness that not only takes into account the wants and needs of existing taxpayers but also those of future generations.

We all know structural pressures on the budget are increasing over time as the population ages. Slower economic growth – if it’s here to stay – makes growing out of debt far more difficult. So for the sake of fairness, let’s hope that this government and future ones will continue to help move us to a more sustainable budget position.

Recent Comments